The stock market crash of 1987: What have we learned?

- Published

Many investors, professional and amateur, were completely shocked

The stock market fell by 22% over two days in October 1987.

This sharp correction was outside the experience of most City professionals.

It raised fears about this being a repeat of the stock market crash of 1929 and a harbinger of an economic depression to follow.

Both fears proved to be unfounded.

In fact the 100 share index, the main measure of stock market value, ended the year higher than it had started.

So anyone who had sat on their hands during the crash saw the value of their investments recover swiftly.

It was not until early the next decade that we experienced another economic recession.

However the experience of 1987 provided lessons, not all of which have been taken on board even 25 years later.

Out of line

The events of October 1987 need to be put into perspective.

The UK stock market had risen by 47% from the beginning of that year to mid-July, and this strong performance had followed gains in each of the previous five years.

There was a strong suspicion that a stock market bubble was appearing, with valuations out of line with the economic reality of the time.

Investors were carried away with the euphoria that shares would keep rising.

This was not to last however.

Wall Street had begun to weaken through the summer months and was particularly weak on the Friday before "Black Monday".

Also, many in the City were unable to get to their trading desks that day because of the disruption caused by the storms over the previous night.

Circuit breakers

Monday morning, 19 October 1987, therefore began with London catching-up with Wall Street's weakness.

Renewed selling pressure, particularly after lunchtime when it became clear that Wall Street was again going to open well down, caused many to panic.

The tide of sell orders turned into a flood as investors tried to cash in on the profits made over the previous years.

The selling continued on the Tuesday and the markets remained weak into November, until the combination of sharp falls in interest rates and more realistic valuations tempted investors to return.

As mentioned, the market ended the year higher than it had begun, despite this turmoil, and there were few signs that the real economy had been negatively affected by these stockmarket gyrations.

There were however lessons to be learned.

The authorities introduced "circuit beakers" to suspend trading in share prices that have become extremely volatile.

These have been used several times since and serve to limit any potentially negative secondary affects of excessive stockmarket volatility .

'Irrational exuberance'

However some lessons have not been taken on board, as became even more obvious during the later stock market boom and bust of 1999 to 2003.

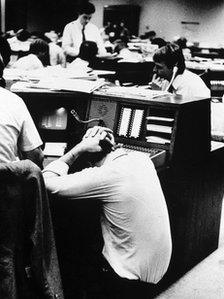

New York stock exchange trader on 19 October 1987

Central bankers still do not seem convinced that asset prices, as well as consumer prices, should be taken into account in setting interest rates and monetary policy during the boom years.

For instance, Alan Greenspan, then the chairman of the US central bank the Federal Reserve, famously dismissed the stock market bubble of 1998-2000 as "irrational exuberance".

However he did nothing about it, arguing that central banks cannot predict financial bubbles and should react to busts rather than booms.

In my view, he and other central bankers could have done more to limit the periods of cheap money and east credit that have fuelled stock market booms.

When you have a prolonged setback in the stock market it can in fact have an impact on the economy.

We have seen, since 2007, that the fall of the stock market - and also house prices - has had a major impact on consumer confidence in the UK and hence spending in the economy.

What about investors?

They received another reminder that shares are for the long-term and should be avoided if you cannot live with short-term volatility.

The opinions expressed are those of the author and are not held by the BBC unless specifically stated. The material is for general information only and does not constitute investment, tax, legal or other form of advice. You should not rely on this information to make (or refrain from making) any decisions. Links to external sites are for information only and do not constitute endorsement. Always obtain independent professional advice for your own particular situation.