The young and the restless

- Published

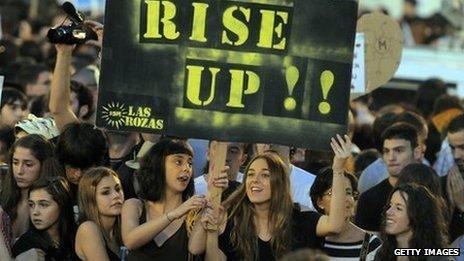

Anti-cuts protests in Madrid

Young people were among the hardest hit by the global recession, and youth unemployment will continue to be a risk factor for social and political instability worldwide, writes Jonathan Wood, of business risk consultancy Control Risks.

The Arab Spring, Europe's anti-cuts protests, the global Occupy movement, and the London riots of 2011 all raised questions about the links between youth unemployment and social unrest.

While the main driver of youth unemployment is economic weakness, government cuts have exacerbated the situation by reducing public sector workforces, cutting unemployment support and raising education costs.

In the United States, youth unemployment leaped by one-third during the economic crisis to above 17%, where it has remained.

In the European Union, youth unemployment hit 23% in August 2012, and in Spain and Greece most young people are now out of work.

The duration of youth unemployment has increased. In the UK, for example, the percentage of unemployed young people out of work for longer than one year has nearly doubled since late 2008.

Even emerging markets, which weathered the crisis better and recovered faster, face significant challenges.

The Arab Spring, driven in part by demands for jobs, damaged tourism and business investment, hurting job prospects further.

South African youth unemployment rates, meanwhile, have held steady at more than three times the global average, and more than a million young people in South Asia lost jobs during the global recession - second only to Europe in sheer numbers.

As a result of these trends, fears of a "lost generation" are mounting at the global and national levels.

Yet the slowing global economy offers a bleak outlook for youth unemployment over the medium-term.

Without stronger growth, it seems unlikely that the global economy can generate enough jobs to employ the estimated 100 million young people entering the labour force each year, let alone the tens of millions of ageing workers staying in work.

Unemployment risks

There is no clear link between youth unemployment and political instability or conflict.

Youth unemployment was only one of many grievances fuelling the Arab Spring and was at best a backdrop to the London riots, which were sparked by a police shooting.

It has featured most prominently as an issue in anti-austerity and Occupy protests in Europe and North America, but again as part of a broader reaction against public spending cuts.

These cases suggest that youth unemployment is indeed a risk factor, but not necessarily a trigger, for social and political instability.

On one hand, youth unemployment often symbolises and accentuates deeper economic or social grievances.

In the Middle East and North Africa, for example, persistent high youth unemployment highlighted economic mismanagement by authoritarian regimes and "unjust" labour markets shaped by family or political connections.

Spanish and Portuguese protest movements, meanwhile, were triggered by austerity plans that seemingly validated concerns about banks, trade unions, and other vested interests.

On the other hand, poor employment prospects determine how young people perceive and respond to government actions.

Disruptive and occasionally violent student protest movements in Chile, Quebec, London and elsewhere over the past two years revolved, in part, around anxiety over post-graduate job opportunities and the ability to repay educational loans in the wake of education spending cuts.

Outlook for instability

The World Bank rightly notes, in its recent report on global jobs, that access to jobs and stable employment are key planks of social cohesion.

Tight competition for scarce jobs can divide communities, especially when immigrant groups are involved.

Persistent and long-term youth unemployment undermines the legitimacy of economic arrangements, as protests from Tahrir Square to Wall Street attest. It also makes it easier for illicit organisations and activities to capture the allegiance and esteem of young people, especially young men.

The long-term implications of a breakdown in social cohesion due to persistent youth unemployment are difficult to assess. But if a "lost generation" materialises - in Greece, Egypt, South Africa or elsewhere - policymakers and businesses alike will be dealing with the challenge of youth unemployment for a long time to come.