Doing Business in China

- Published

David Kedwards spent most of the last 11 years running his company's mainland China business

Wall Street English is a subsidiary of the Pearson media and education group that teaches English as a foreign language in 27 countries worldwide.

When I started in 2001, we had one centre in Beijing. As of today, we've got 63 centres in nine cities across China.

In all, we've dealt with about 250,000 students since we first set up here.

The biggest single constraint on our growth has been getting the right staff. Otherwise we'd have twice the number of centres, the demand is so strong.

Our staff have to have the business skills, the language skills and also the right business etiquette.

Under communism, the education system has not yet caught up with the enormous demand for skilled managers capable of operating in highly matrixed multinational corporations.

There is a huge dearth of this kind of talent.

If you give people orders in China, they will follow them very carefully. But people don't always show enough initiative or creativity.

Thirst to understand

We offer a super-premium product and are more expensive than our competitors.

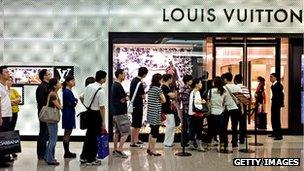

In the big cities in China, there are luxury shopping malls the like of which you wouldn't believe.

Like the country's many luxury shopping malls, the Wall Street Institute caters for China's new elite

Like those malls, we are targeting the top layer of society, which is actually quite narrow, but which has a lot of money to spend.

Typically our students are 25-to-40-year-olds, largely white-collar folk, looking for English to help with their career. English being the global language of business, it will open more doors for them.

We don't see Mandarin replacing English as a business language in East Asia. Of the three main international financial centres in the region - Hong Kong, Singapore and Tokyo - two of them are English speaking and are based on British business rules and principles.

Many senior people in the Communist Party and in the regional governments are also learning English. These people are the creme de la creme.

There is a relentless desire for education in this country. There is a great tradition of learning. Teaching is a glorified profession - in contrast with the West.

The thirst to understand what is going on in the rest of the world is enormous. Maybe this is something to do with the restrictions on communication and the media in China.

People are open to foreigners and foreign influences.

All of our teachers are native English speakers - from Australia, the US, Britain, South Africa - and increasingly we are recruiting directly from overseas.

For a Chinese student, it is a big deal to get access to a foreign teacher.

Level zero

In the Chinese education system, people are taught by rote. They memorise a lot of language, but cannot actually use it.

Generally speaking, our students will have been exposed to some English at school, but it is often only after they finish school that they switch on and realise that they need English in the real world.

Our approach is not prescriptive. We're not here to teach people how to pass a language exam to get into a university or for foreign immigration.

We use a "blended learning" approach. It means that we have to explain to students that they will be doing a lot of the learning on their own.

About 60% of the curriculum involves students interacting with our proprietary software, 30% is with teachers, and the rest is homework and other assignments.

Eleven years ago there was a huge problem of getting people to interact with a computer instead of a teacher. There was culturally a lot of resistance.

As the world has become more digital, we have seen a sea-change in attitudes, and the kids coming through now are much more comfortable dealing with the internet, using their iPads and so on.

Our software is now available online, and we are also looking to provide online classes.

In China and a couple of other Asian countries - Korea, Japan - the issue of "face" is critical.

In China, teaching is a valued profession

We had to work hard to make people more expressive, and more confident to expose themselves and make themselves vulnerable.

To improve confidence, we set up a social club to supplement our teaching activities, to allow for free conversation in an informal setting.

For many Chinese the very basics of the English language, such as the characters we write with, are new.

So we invented a new product in China called "Introduction to English". In other countries we have teaching levels one to 17. In China we had to invent a level zero.

Brown envelopes

Another issue in China is the bureaucracy.

There are agencies and departments for everything. There are many different licences you have to get, and each licence is limited in scope.

Negotiating licences and dealing with vendors is not necessarily straightforward.

Sometimes people make suggestions like: "My kids are coming up for college soon and it's very expensive."

We've avoided games with brown envelopes - we knew that we eventually wanted to sell the business to a multinational corporation that would have strict compliance criteria.

Fortunately, because of our high profile as a premium brand, the bureaucracy was willing to work with us and we could still get things done.

The government here is very smart, and if they see that you are the best in class, they will be delighted to see you set up shop in China because they know that it will help the diffusion of knowledge into the country.

We raised our profile by making donations to government programmes such as the Shanghai Expo, and the "Go West" programme to develop the interior of the country.

We also hired a couple of key people who used to work in the department of education.

They helped reinforce the quality of our product and increased our credibility.

The opinions expressed are those of the author and are not held by the BBC unless specifically stated.

- Published31 October 2012