Human rights activists taught online tactics

- Published

Mobile phones have brought information and images from conflict zones

An international training institute to teach online tactics for human rights campaigners is being set up in the Italian city of Florence.

The first students, starting in the new year, will be drawn from human rights activists around the world - with the aim of arming them with the latest tools for digital dissent.

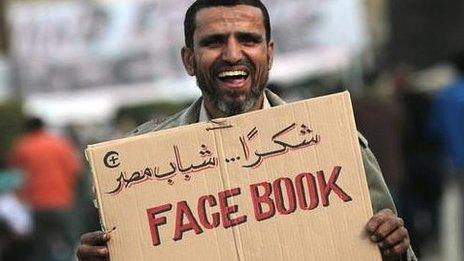

As the Arab spring showed, protests are as likely to be about individuals using social networking as much as public demonstrations. Street protests have become Tweet protests.

And repressive regimes are as likely to be hunting through Facebook as they are raiding underground meetings.

There is a dangerous, high-stakes, hi-tech game of cat and mouse being played - with protesters needing to balance their secrecy and safety with their need to achieve the maximum public impact.

This training centre, being set up by the European wing of the US-based Robert Kennedy Center for Justice and Human Rights, wants to combine academic study with practical skills and training.

Screen secrets

With an appropriate symbolism, the training institute is based in a former prison building, donated by the city of Florence.

The formidable jail doors, with their hatches and bolts, are still visible.

A former prison building in Florence will be the base for the training institute

Federico Moro, the director of the project, says the intention is to use "technology to promote democracy, human rights and justice".

"The idea is that with social media you can achieve change," he says.

He says campaigners might have passion and belief in their struggles, but they also need practical knowledge.

"Human rights leaders might dedicate themselves to a cause, they might give their soul and their life - but you still need the skills to generate change," he says.

These students will be blog writers and campaigners, who will be able to study in Florence on scholarships provided by the Robert Kennedy Center. Recruiting will be complicated by the need to protect the privacy of people who might be put at risk even by applying.

Mr Moro says the institute will not be partisan in supporting either right- or left-wing causes - but will act in defence of individuals facing violations of their human rights, whether it is political oppression or domestic violence.

Beating the censor

As well as teaching individuals, the institute wants to provide information for organisations and businesses, advising on areas such as human rights legislation and ethical investment.

But what does a digital activist - or a so-called "smart dissident" - need to know?

Chris Michael, from the Brooklyn-based human rights group Witness, describes the practical steps that protesters are using to stay ahead.

Kerry Kennedy leads the human rights foundation set up in memory of her father, Robert Kennedy

There are websites that allow for anonymous internet access, allowing people to organise without revealing identities. There are also means of circumventing censors' attempts at blocking websites.

The Tor project software, an unexpected spin-off from military technology, is favoured by human rights campaigners.

Mr Michael says there are also "work arounds" to make online video and phone calls more secure from surveillance.

Another practical development is software that can easily pixellate faces in video footage, protecting bystanders who might be put at risk by identification.

In terms of posting videos of protests or repression, Witness is working with YouTube on a dedicated human rights channel.

It's already hosting hundreds of user-generated videos from a wide number of countries, at the moment including Syria, Pakistan, Libya, Burma, Chile, Spain, Russia, China and the United States. There's a daily update of video reports which include anything from student protests to forcible evictions.

Selecting and showcasing the most relevant videos is important to make an impact on YouTube's global audience, Mr Michael says.

"Very few people are going to watch for hours. You might be able to get their attention for 45 seconds, that's the world people live in," he says.

Mobile range

The spread of mobile phones means there is an unprecedented ability for recording and distributing evidence of violence against citizens. We're living in a global goldfish bowl.

But is this making the world a safer place? Can cheap video and social networking defrost dictatorships? To put it bluntly, could Hitler and Stalin have been exposed at an earlier stage by Twitter and YouTube?

The Arab Spring saw social networking becoming a forum for protest

Does a modern revolution really come from the lens of an iPhone rather than the barrel of a gun?

It's not that simple, cautions Mr Michael, speaking at an event in Pisa, Italy, debating the impact of digital activism.

"In one word, Syria," he says. There has been video evidence of wrongdoing and violence, but little sign that public scrutiny is acting as a deterrent.

"Just because you can document something, it doesn't meant that you change anything in real terms."

But he says the sheer scale of video and information - and the ability to keep in touch with those under attack - does make a difference.

"Because so many people are documenting, seeing is not only believing, we're also able to act and communicate with people who are affected - and that can be very powerful."

'Slacktivism'

But the question remains whether Facebook really enabled Arab revolutions, or whether it enabled the rest of the world to find out more about a revolution that was going to happen anyway.

Federico Moro, director of the training institute project, with a statue of Robert Kennedy

Stephen Bradberry, a community activist in New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, uses the word "slacktivism" - as a caution for the idea that clicking on a "like" button is a sufficient alternative to grassroots organisation.

He also makes the point that while the internet makes so much information accessible, the power to find it is handed over to the search engines and their algorithms.

Rana Husseini, a Jordanian activist and journalist who uncovered stories about honour killings, says the internet has given a voice to public opinion.

She also shares concerns that digital technology can be used as tools for surveillance and control as well as openness and investigation.

But she speaks passionately about the way that ordinary people risk their lives to record video clips on their mobile phones in conflicts such as Syria.

"This couldn't have happened in the past - and probably this person will vanish."

But the act of documenting is an important statement in its own right, she says. The idea of so many individuals making their own video history in this way is "something new and important".

Outsiders' voices

As an educational project, the human rights training institute project in Florence is an unlikely collision of influences. It's a highly individual project.

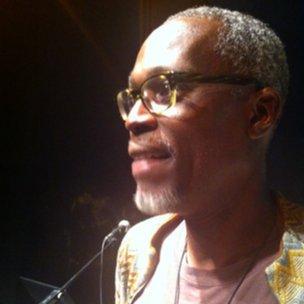

Stephen Bradberry warns of the risk of relying on online campaigns instead of grassroots protests

Inside the sturdy medieval prison walls, in the birthplace of the European renaissance, there is this hi-tech centre for online civil rights, awaiting students from around the world.

Into this mix is added the legacy of Robert Kennedy's 1960s idealism. The foundation was set up in memory of the assassinated senator and is now headed by his daughter, Kerry Kennedy.

She recently had her own brush with the secret police when she headed a human rights delegation to the Western Sahara.

A trademark of Robert Kennedy's campaigning was to get information first hand, often from people excluded from the political mainstream.

And there is some kind of symmetry here - with social networking and blogging representing an instant electronic version of accumulating the authority of many individual voices.

They want to harness these new digital technologies to old causes.