China: Does it have to become more like us?

- Published

- comments

Many in the West have a shaky grasp of China's internal power dynamics, but they are confident about one thing - that China is facing a key moment on its path to economic development, and that it will grow into a rich economy only by becoming a lot more like us.

In public, at least, China's leaders would sign up to the first part of that statement. But they don't seem to agree on the pace of reform that is required - or its ultimate direction. They think that China - the "middle kingdom" - can get rich on its own terms, not by simply mimicking everything that happened in the West.

But of course, there is a third possibility, that it doesn't get rich at all. The lesson of centuries of economic history is that China is likely to get stuck in the middle: neither a poor economy nor a rich one.

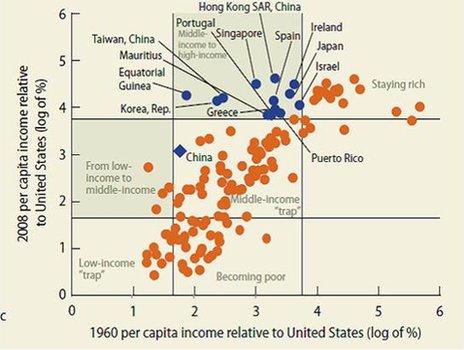

This chart, from the World Bank's China 2030 report earlier this year, makes the point. Of the 101 countries that were "middle-income" in 1960, only 13 had managed to break from the pack to become advanced economies by 2008. It's interesting to note that only three of those 13 countries has a population of more than 25 million.

Less than a fifth of the 180 countries in the world have made it to being advanced economies. The rest are low-income or "emerging". You might say it's only a matter of time before others join the club. But most of the countries we now call "emerging" - especially in Latin America and the Middle East - would also have been put on that list, 40 years ago.

One big economic reason why countries get stuck in this "middle-income trap" is that they reach what is known as the "Lewis Point, external". Put simply, this is the point at which a developing country stops being able to achieve rapid growth relatively easily, by simply taking rural workers doing unproductive farm labour and putting them to work in factories and cities instead.

Then there is upward pressure on wages and prices, and growth starts to slip.

Many economists think that China has now reached this point, while its population is ageing fast. Some slowdown in its growth is therefore inevitable. The question is how much.

China has grown by just under 10% a year, on average, since 1980. If it can grow by at least 6% or 6.5% a year from now on, the World Bank reckons it can graduate to become a high-income country before 2030 and overtake the US as the world's largest economy. (China's income per head, of course, would still be much lower than America's.)

Six or 7% growth doesn't sound so hard, for a country that has defied the sceptics for so many years with its continued economic success. But from where it is now, growing at that pace would mean China transforming itself from a country driven by exports, manufacturing and investment to one centred around domestic services and consumption.

Investment and consumption each now account for around 50% of China's GDP. To achieve sustainable growth from now on, the World Bank thinks the consumption share needs to rise to about 66% - and investment to fall by a similar amount.

Every developed economy has made this fundamental transition. But few, if any, have done it while continuing to increase productivity - output per head - by 6-7% a year. America, Europe and Japan had the advantage of a growing labour force for most of this stage in their development. China will not. Its population is ageing much more rapidly and its labour force will be shrinking after 2016.

How will that happen, if at all? The World Bank has a long list of answers, but most of them come down to increasing the amount of competition in the economy and fostering innovation.

This is where the "becoming more like us" part comes in. It's conventional wisdom in the West that you can't foster innovation without strong property rights, for example. Many would also put a free press on that list - and what the World Bank euphemistically calls "higher public participation in public policy formulation".

The World Bank is prohibited - by its founding statutes - from saying that democracy is better than other forms of government. Instead, in its 2030 report the Bank offers China's leaders this deliciously delicate piece of wisdom:

"As economies grow in size and complexity, the task of economic management becomes more complicated, and governments usually find that they alone do not, indeed should not, have all the answers.

"Governments, therefore, tend to tap the knowledge and social capital of individuals and non-government agencies, including universities, communities and think tanks.

"One of the hallmarks of advanced economies is their public discussion of public policies. Indeed, such discussions are already beginning in China, but there is a long way to go."

You might be tempted to call all of that democracy. The World Bank couldn't possibly comment. But you can see why, to many outside experts and commentators, the job of transforming China's economy and its political system seem to run together.

They don't see how you can become the kind of country that produces the Googles and Facebooks of tomorrow and puts the consumer in the driving seat without also becoming a more open and democratic society.

China's leaders think you can have modern economic success without - in the medium term at least - a modern democracy. Many in the West disagree. That could be a reflection of Western arrogance. But it's possible that they're all wrong. China may well not look like us in 20 or 30 years' time, but it might not look like an advanced economy, either.