Holy pension hole

- Published

- comments

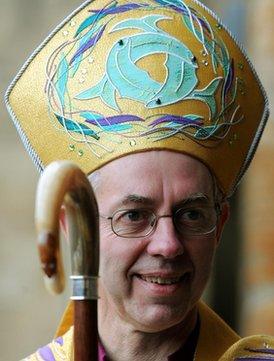

The Bishop of Durham Justin Welby is expected to be named as the next Archbishop of Canterbury

The Old Etonian apparently due to be named as the new head of the established church has a huge, unsustainable financial deficit to shrink - which is perhaps redolent of the challenge faced by another Old Etonian who became head of government in 2010.

A bit like David Cameron who inherited a gap between tax revenues and public expenditure equivalent to a horrid 10% of GDP, one of the most pressing problems to be faced by Justin Welby as the new Archbishop of Canterbury is a massive hole in the fund that pays the pensions of retired clergy.

I am told that the current Bishop of Durham, a former oil industry executive, is good with money. He will need to be.

A new report on the Clergy Pension Scheme by the Archbishops' Pensions Task Group points out that the deficit in the fund -which is liable for all clergy pensions earned after January 1998 - ballooned from £262m to a peak of £507m in November 2011.

The Task Group includes the First Church Commissioner, Andreas Whittam-Smith, an unusually saintly and numerate erstwhile hack - who gave me my big break in journalism, by recruiting me to help launch the Independent newspaper in 1986 (goodness it feels such a long time ago).

He and his two colleagues believe the deficit has "fallen back somewhat", but that the December 2012 actuarially measured deficit will be somewhat greater than it was three years ago.

How much greater? Well a research note by the pensions consultant John Ralfe calculates the hole at the end of last month as approximately £500m.

This represents quite a potential burden for parishioners. Ralfe calculates that without further reductions in pensions payable to clergy, individual dioceses would have to make contributions to the fund equivalent to a staggering 60% of the value of salaries, up from an already high 38.2% (clergy themselves don't make contributions to the cost of their pensions; the liability falls on their employer).

Now the Task Group is clear that it would be wrong to rush into draconian pension cuts or radical overhaul of pension provision. But it notes the need to "balance the financial pressures on funders with the obligation to protect the interest of future pensioners".

There are a few salient points to make. First, clergy pensions would not be seen by many as lavish and egregious. For example, the pensions of the Archbishops of York and Canterbury will be in a range from £21,000 and £28,000, according to the annual report of the Church's Pensions Board - so perhaps 2% or 3% of the pension Mr Welby might have earned if he had got to the top of one of the oil companies that employed him in days of yore.

Second, the Church is jolly unusual in retaining its faith in equities or shares.

As you will know, there has been a huge shift by most pension funds out of shares and into bonds. And as the FT points out this morning, for the first time ever UK pension funds now hold more bonds than equities: the Pensions Regulator shows that UK funds hold 43% of their assets in gilts and fixed-interest debt compared with just under 39% in equities.

But the Church did not join this herd galloping into the debt sold by governments and companies. On my calculations of the asset allocation in the Church of England Funded Pensions Scheme, 84% is held in shares, property and derivatives - or what are perceived to be riskier assets.

As it happens, the Church's unfashionable refusal to abandon the cult of the equity has not gone wholly unrewarded: over the three years to the end of December 2012, the return on the assets was 7.1% per annum, which compares quite well with some mammon-obsessed hedge funds.

'Through the roof'

The problem - characteristic of the pensions industry in general - is that liabilities have gone through the roof. And the proximate cause is the soaring price of bonds, and the collapse in the yield on those bonds.

The explanation is that the earth-bound Pensions Regulator has less faith than the vicars in equities. So the way it measures liabilities is to calculate the quantity of assets a pension fund should ideally hold to meet future pension payments if all those assets were in low-risk bonds.

What this means is that when the income generated by bonds falls, as it has been doing, any pension fund would theoretically have to hold massively more of those bonds to meet the cost of future pension payments. And the point is that for all the decent performance of the shares and property held by the Church's pension scheme, their aggregate value is several hundreds of millions of pounds less than would be needed if they were cashed in and converted into allegedly safer bonds.

There is of course a very interesting question whether the risk aversion of the regulator is more or less rational than the priesthood's apparent appetite for risk. But the problem for the new Archbishop is that on this sort of non-spiritual, fiduciary issue, his authority is rather less than that of the officers of the state.