Is Ethiopia ready for foreign investment?

- Published

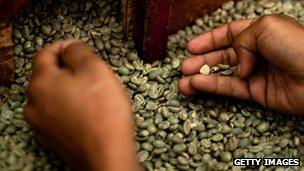

Principal cash crops in Ethiopia include coffee, pulses, oilseeds and cereals

Ethiopia was once a byword for poverty and famine.

It is still one of the poorest countries in the world, with an estimated third of the population earning less than $1 (63p) a day, but the country also has one of the world's fastest growing economies.

Opinion is sharply divided, however, as to whether or not it is wise to invest in the country.

Since 2004, its economy has been expanding by about 10% a year. The government expects growth to continue in double digits - but a report by the International Monetary Fund, external (IMF) suggests it will slow to 6.5% in 2013.

Even the IMF predictions are impressive, however, considering the current global financial climate and the fact that unlike many other countries on the continent, Ethiopia does not have much in the way of natural resources.

Entrepreneurial spirit

Coffee is one of the biggest export earners in Ethiopia.

In Addis Ababa, the country's capital, coffee exporter Michael Girma says it was a challenge to launch his business.

"To start up in the export sector, you need to perform with your own cash. Then after that, you can approach the banks," he says.

Apart from exporting coffee, he now also owns a cafe, a bar, and a pizzeria, employing 140 people altogether.

Although the business environment is getting very competitive, he is achieving a profit margin of 20-30% each year and feels confident about the future.

"A lot has changed in the last seven years," he says. "You need to be aggressive, but not arrogant."

Although foreign investors are encouraged, many sectors are reserved for domestic investors.

"The restricted sectors are those which supply to the local people. If foreign investors want to come in and invest in projects which are export oriented, anything is open," he says. "It would be very hard to compete otherwise."

Diverse opportunities

Despite annual high inflation, some investors think the potential in Africa's second most populous nation has not been recognised.

Agriculture plays an important part in the lives of many people in Ethiopia

Earlier this year, Shultze Global Investments launched a $100m equity fund aiming to invest in Ethiopian businesses.

In a nondescript building on a hillside overlooking Addis Ababa, Berhane Demissie decides where to put that money.

"Ethiopia offers significant opportunities for investors," she says, pointing out that agriculture is a strong growth sector.

"Anything grows in Ethiopia with the various climate and soil diversities that we have. That also follows through to the agricultural value-added chain with processing and exports," Ms Demissie says.

With 85% of the population dependent on the agricultural sector, she says the government is trying to ensure those farmers have access to finance and fertilisers that will allow them to grow more.

Ms Demissie says this will lift people out of poverty.

"If the programme was just about big farms I would have said no, but the smallholder farmers are being included in the overall growth of the economy," she says.

She also says there is a lot more demand for consumer goods and services within the country, but too few manufacturing companies.

Business concerns

In 2010, Transparency International, which rates countries according to perceived corruption, listed Ethiopia at 120th out of 183 countries and the Washington-based Global Financial Integrity research organisation concluded that illicit financial outflows between 2000 and 2009 totalled $11.7bn (£7.4bn) in 2009 - which was more than Ethiopia had earned through exports.

It is reports like those which deter some of the diaspora from returning to the country to look for business opportunities.

Berhanu Nega went back to Addis Ababa in 1994 after the change in government and was elected mayor in 2005 - only to find himself imprisoned for life on the day he was elected on charges of treason, because he had called for the overthrow of the president.

He was released after 21 months and returned to the US where he is now an economics professor at Bucknell University. He is also the co-founder of Ginbot 7, an Ethiopian opposition party, and he does not believe the country is a good place to invest in for the medium or long term.

"If you want to make big bucks and get out then it is good for the short term," he says.

Apart from concerns about corruption, he is also worried about the uncertainty of inflation: "The government has been printing money since 2005 and inflation, depending on which figures you look at, ranges between 40-60%."

He says many businesses have closed down because of the taxation the government has imposed to pay for its expanded security forces.

He adds: "The government has been pushing tens of thousands of people off their lands because of the land grabs by China, Saudi Arabia and India among others, which has caused serious conflict in many areas."

He does not feel there will be any changes soon and is pessimistic about the country's future business environment.

- Published15 October 2012

- Published17 January 2012