Is the government borrowing less this year?

- Published

There has been much confusion about whether the government is going to borrow less money this year than it did last year.

In other words, will the deficit be lower in the financial year 2012-13 than it was in 2011-12?

This is a crucial political question.

The chancellor had to reveal the bad news that it would take longer than planned to start reducing the overall debt (that's all the deficits added together) than he had hoped.

But he gave great fanfare to the news that the independent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) had predicted that this year's deficit would be below last year's.

"There are those who have been saying that the deficit was going up this year," he told the House of Commons.

"But any way you present these figures, that is not what the OBR forecasts show today. They say that the deficit is coming down."

Mobile phone auction

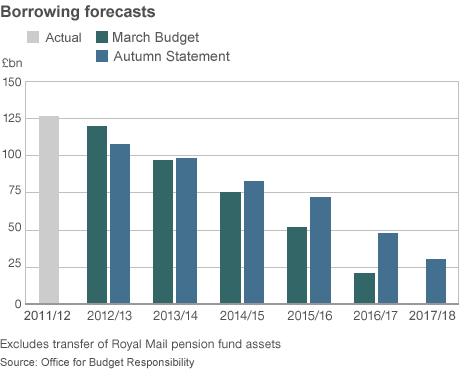

The OBR does indeed predict a fall in the deficit, from £126bn in 2011-12 to £108bn in 2012-13.

But the judgments behind the figures are fiendishly complicated.

Among the questions is whether you take into account the assets of the Royal Mail pension scheme.

The Treasury took over the assets of the scheme in April 2012, which wiped £28bn off the deficit. But the liabilities of the scheme will cost the Treasury money in the future, so some have argued that the benefits should have been excluded.

The deficit figure for this year is also flattered by the £3.5bn sale of licences to run 4G mobile phone services.

BBC economics editor Stephanie Flanders says that without the boost from the spectrum auction the deficit would have risen.

She asked Treasury minister Danny Alexander if that should not have been excluded as a one-off factor but was told that there were one-off sales included in the figures every year.

To make matters even more complicated, the OBR has had to decide how to treat a chunk of money held by the Bank of England as a result of its quantitative easing programme, under which it has created money and mainly used it to buy UK government bonds.

Simon Gompertz explains the difference between 'debt' and 'deficit'

The government has been paying interest to the Bank of England for those loans, which has accumulated into a big pot of cash.

The Treasury has decided to transfer that money to itself, which has knocked £11.5bn off the deficit this year and will continue to reduce it for several years to come.

On the flip side, once the Bank of England begins unwinding the quantitative easing programme, the deficit will rise again, so one could see the transfer as a temporary effect.

Indeed, the Office for National Statistics, which calculates the national accounts, will not decide how it is going to treat these money transfers until next month, and the OBR points out that its forecasts could be affected by its decision.

Finally, the assets of Bradford and Bingley and Northern Rock Asset Management have been reclassified as part of central government, which has knocked another £400m off the deficit.

This is not to say that there is anything dodgy going on or that the accounting practices would not be supported by independent organisations or followed by other countries.

But excluding the effects of the Bank of England money gives a figure of £121.4bn in 2011-12 and a forecast of £119.9bn for 2012-13, which demonstrates the importance of the inclusion of the assumed receipts from next year's 4G spectrum auction, without which the deficit would indeed have risen.