The great London airport debate

- Published

Last year the government decided to kick any decision about building new runways around London into the long grass.

Former Confederation of British Industry head Howard Davies has been put in charge of a commission of inquiry, external.

He has been told not to come back with any recommendations until after the next elections in 2015, although he is allowed to rule out any options deemed patently unviable before that date.

End of story, you might think.

But, in fact, the announcement has kicked off a whole new debate about whether and how to deal with the South East's crowded airports.

Partly this is due to hopes and fears that the move heralds a secret change of heart by the Tory leadership over their opposition to any further expansion at Heathrow.

Partly it is because many see the commission as a unique opportunity to lobby for their own pet solution.

Here are some of the big questions that Mr Davies will be mulling.

Do we really need more capacity?

"We needed it yesterday," says Peter Budd, head of aviation at engineering consultancy Arup. "The issue is the resilience of the provision. Every time there's a problem with the weather, Heathrow goes up the pole."

Heathrow is already operating at close to what is deemed full capacity. However, there is a lot of room at London's smaller airports, and according to the Department for Transport, external, Gatwick and Stansted will not be chocker until 2030.

Long-term forecasting can be a thankless task

But full capacity is not where you want to be, according to Mr Budd. Airports need a certain amount of wiggle room to keep everything running smoothly - which is precisely where Heathrow comes unstuck.

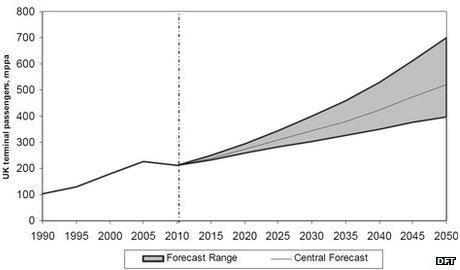

Passenger numbers, and equally importantly cargo, are forecast by the Department for Transport (DfT) to resume their steady growth after what has been a four-year recession-induced hiatus.

Since World War II, air travel has grown at roughly twice the rate of economic growth.

However, Richard George, energy campaigner for Greenpeace, thinks the DfT underestimates how steeply the cost of flying could rise in the future.

"Air travel is already far too cheap," he says. "Airlines pay no VAT or fuel duty, and ticket prices do not reflect the cost to the environment of noise pollution or greenhouse gas emissions."

If the UK is to stick to its target to cut emissions by 2050, taxes will surely have to rise, Mr George says.

The DfT also assumes no increase in the oil price by 2030.

Yet demand for air travel, and energy generally, is rising quickly in China and other developing countries - something likely to push up prices for the rest of us in future, as the world's oil resources deplete.

Even so, others doubt that rising prices will choke off demand.

"Low cost airlines have given people the bug for flying - people who weren't flying before," says David Kaminski-Morrow, air transport editor at industry magazine Flight International. "I don't think you'll be able to claw that back."

And Arup's Mr Budd points out that economic growth in China also means more Chinese tourists flying to London.

Do we need a hub?

A hub airport is one that hosts a lot of connecting passengers - people arriving say from New York and flying onto Mumbai, without ever leaving the terminal building.

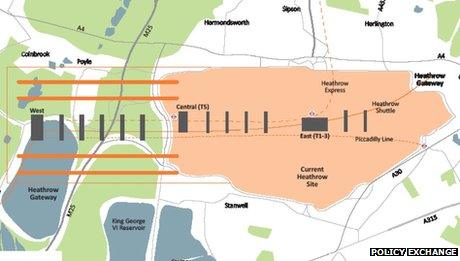

The standard argument for the UK hosting a hub is laid out in a proposal from the think tank Policy Exchange, external, which advocates rebuilding Heathrow at double its current size.

The Policy Exchange proposes doubling the size of Heathrow

People flying intercontinental prefer major, well-serviced routes, and therefore often have to change planes, the argument goes. It is efficient for the airline industry to connect all those major routes in a single hub, where every arrival can connect smoothly to every destination.

If you get to host your continent's main hub, you benefit from direct flights to every corner of the globe. That makes your city a much more attractive place for global businesses to invest.

The evidence to support these claims is largely anecdotal. Mr Budd points to Dubai - a city that has seen rapid growth in airport capacity and in business, leisure and trade facilities. But it is hard to say which caused which.

As the South East's only two-runway airport, Heathrow currently enjoys hub status.

"The budget carriers end up at Stansted - they're servicing people who aren't using London for transit," says David Kaminski-Morrow. "London Gatwick has a lot of holiday carriers, and big airlines who can't get into Heathrow."

For example, after the EU-US open skies agreement opened Heathrow up to more competition, all the US airlines chose it over Gatwick, despite the landing slots being considerably more expensive.

But Heathrow faces competition from Paris, Frankfurt, Amsterdam and even Dubai. All four are major Heathrow destinations, in large part because of the onward flights they facilitate.

The industry complains that while Heathrow has ample direct flights to financial centres like Hong Kong, it has no capacity to add regular services to up-and-coming cities such as Chongqing and Shenzhen.

Incremental or big bang?

If we do go for a bigger hub, there are three options: expand Heathrow, massively expand one of the smaller airports, or build a new hub from scratch (with several proposals for locating it in the Thames estuary).

A fourth option - linking Heathrow and Gatwick via a fast transit link - is a non-starter, according to David Kaminski-Morrow: "As a passenger, I get annoyed if I only have to change terminal building in transit!"

The government has previously ruled out Heathrow expansion

Heathrow needs capacity urgently, according to Mr Budd. And it already has so much going for it - the hub status, a massive locally resident workforce, excellent transport links. That was the logic behind building Terminal 5 and a mooted third mini-runway.

The problem is that Heathrow is in a dreadful location.

Because of the prevailing westerly wind, Heathrow, like most airports on the planet, operates on an east-west alignment. Unlike Heathrow, most other major airports in the world are therefore located either north or south of the city they serve, meaning low-flying aircraft do not pass directly over the city.

The big bang approach has the advantage not only of picking the least-bad location, but also of building a state-of-the-art airport from scratch.

It would likely involve replacing Heathrow, according to Mr Budd at Arup - either by rebuilding Heathrow itself (as proposed by the Policy Exchange), or by closing it in order to shift its hub value to the new location, as proposed by Heathrow itself, external.

But any such undertaking would be expensive and enormously disruptive - relocating workers, building transport links, completely reorganising densely-used airspace - and would require a lot of long-term planning.

"Airports take longer to build than politicians are usually in power," says David Kaminski-Morrow, which means the case for building a new hub airport from scratch rarely gets a fair hearing.

What would make an ideal airport?

Modern major airports usually conform to some basic rules:

Runways need to be parallel and distanced at least 0.6 miles (1km) apart, to make sure that they can be operated independently. Otherwise aircraft have to be co-ordinated to make sure that they don't land at both runways simultaneously - a problem that afflicts Frankfurt Airport.

Terminal buildings are located between the runways at right angles, giving aircraft immediate and easy access.

Terminals comprise a major building and a set of islands, linked by an airport transit system, as at Heathrow Terminal 5, which enables easier connections and fast-tracking travellers with hand luggage only.

The resulting layout, known as a "toast rack", is well exemplified by Hartsfield-Jackson Airport in Atlanta, the world's busiest.

The best location is of course a vexed question, and depends on the criterion. A rundown of the options can be found here.

North of London would provide the easiest access to the rest of the country, and would avoid planes having to fly directly over the London suburbs.

But most suggestions have instead focused on the more politically acceptable Thames estuary, which benefits from having very few local residents.

However, an estuarine location too close to London still risks sending planes over the East End, while a more distant location would be much harder to link up to London and the rest of the country.

And much of the lower Thames is populated by birds that risk being sucked into jet engines with dangerous consequences.

What can be done about noise pollution?

Even if the number of planes flying to and from London does increase, does that necessarily mean more noise blight for residents?

Aircraft are undergoing two major technological revolutions that are helping to reduce noise.

Firstly, the planes themselves are being made much quieter, thanks to technologies, external such as noise-absorbing linings around engines, and chevrons that create quieter air vortices inside engines, along with a lot of wind-tunnel testing.

New planes such as the Airbus A380 jumbo are half as loud as their predecessors. Airlines have a strong incentive to buy quieter planes, as they get to pay cheaper landing fees at most airports.

Complaints rose substantially over the summer, peaking at nearly 1,800 in August

Secondly, satellite navigation is allowing air traffic control to pinpoint aircraft far more accurately.

This not only improves safety on foggy days, but also means more planes can be reliably crammed into daylight hours, while mitigating the effect on locals.

Landing and take-off paths can be curved around towns and villages near the airport - admittedly not much help over the ubiquitous west London suburbs near Heathrow.

Better navigation systems, along with specialist training for pilots, will also enable much steeper take-offs and landings, meaning aircraft spend less time hovering low over rooftops.

The airline Emirates has called for steeper flight paths at Heathrow as a way of allowing more "quiet" night flights, which are currently heavily restricted, external.

Heathrow also alternates landings and take-offs between its two runways, external, to give West Londoners a half-day's respite, but recently has been dabbling with operating the runways "mixed mode" in order to give itself more flexibility to deal with backlogs.

The Policy Exchange's proposal advocates steeper flight paths, along with a ban on night flights, as quid pro quo for doubling Heathrow's size.

They also suggest moving Heathrow's existing runways two-and-a-half miles (4km) to the west, which is great, so long as you don't live near Sunnymeads, external.

- Published1 July 2015