Has Mario Monti done a good job?

- Published

Mario Monti formed a government in November 2011

Mario Monti is stepping down as prime minister, saying he has lost the support he needs to govern.

He took over from Silvio Berlusconi a little over a year ago, when Italy's cost of borrowing was approaching unaffordable levels and the eurozone's leaders were desperate for credible leadership in the country.

The most important thing he did was in the early days of his government, according to Tito Boeri, professor of economics at Bocconi University in Milan.

"The first stability budget law included pension reform and real estate tax, which were very important for reassuring markets," he says.

"It showed the government was in charge and prepared to take action."

The retirement age was raised to 66 for men and 62 for women, with the age for women rising to 66 by 2018.

The reforms also did away with the system of seniority pensions, which had allowed many public workers to retire at the age of 58.

Italy has a relatively low rate of employment because Italians retire so early.

Avoiding the precipice

But Mr Monti's greatest achievement was not to do with the specifics of pension reform, it was in the restoration of credibility for the Italian political system, according to Fabio Basagni, chairman of Actinvest, a corporate financial adviser specialising in Italy.

"His biggest job was to keep Italy from the precipice," he says.

"The specifics were not as important as establishing the systems."

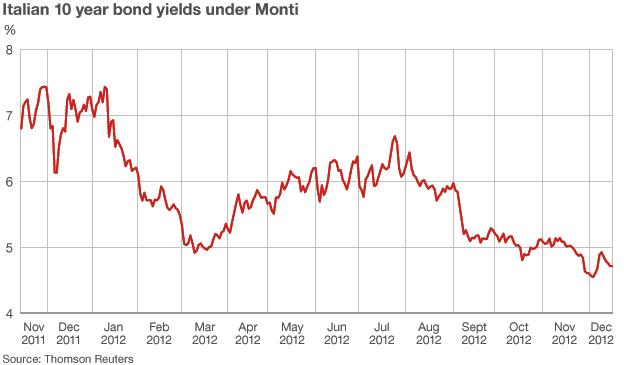

Italy's key problem in late 2011 was that the yield on its 10-year bonds, which are a key indicator of how much it will have to pay to borrow money, was over 7%, which is unaffordable in the long term.

When the unelected Mr Monti formed a government supported by a fragile majority in parliament, Italian bond yields fell to more affordable levels.

The original plan had been for him to stay in power until the end of the parliamentary term in April 2013, but when Mr Berlusconi's People of Freedom party withdrew its support from the government he said he would resign after the budget had been passed, meaning elections would take place in February instead.

"It is important to remember that the largest party in the coalition was Mr Berlusconi's, so there were some things that just could not be done," says Mr Basagni.

"He's done rather well - he could have done better if he'd been supported by a larger majority."

Spending review

Mr Monti's next step was to hold a spending review, which "could have been more effective", according to Prof Boeri.

"It brought a 3bn euro ($4bn; £2.4bn) cut in spending out of a 300bn euro budget," he says.

Some of the more ambitious part of the spending review will not have a chance to be enacted now because of the early election, according to Robert O'Daly, Italy analyst for the Economist Intelligence Unit.

"There was a proposal to reduce the number of small provinces to save money, which has been blocked in parliament and probably will not happen for at least a year," he says.

"My main regret was that he didn't use the high levels of public support when he came in to push harder for structural reforms."

He adds that it was a shame Mr Monti had not managed to do more to deal with the duality of the Italian labour market, in which younger workers are on temporary or fixed term contracts while older workers are on permanent contracts that make it almost impossible to make them redundant.

"Monti gave in to the Confederation of Trade Unions and the final result was far from satisfactory," Mr O'Daly says.

But again, it may be that the importance of the spending review was in the process rather than the results.

"It showed that spending at national, regional and local levels would be closely monitored," Mr Basagni says.

'Right direction'

Prof Boeri would also have liked to have seen more structural liberalisation.

"There are very strict rules about opening pharmacies, for example, with a ceiling to the number of stores allowed in each town," he says.

"Mario Monti marginally raised that number when he should have completely phased out the limit."

"He had the right principles and the right direction, but his policies were not effective enough."

The final judgement on whether Mr Monti's year as an unelected premier has been successful may not be made for some time, because it depends on his legacy.

"Will the serious way he went about governing affect the next government?" Mr O'Daly asks.

"Will the Monti Agenda of fiscal discipline and structural reforms be followed?"

Another part of his legacy may be in the way Italians treat taxes, according to Mr Basagni.

"People protest about paying taxes, but they are less nonchalant about it," he says.

"They have started getting receipts from plumbers and builders."

Mr Monti may have the opportunity to continue shaping Italy's future himself if, as is being reported, he stands in next year's elections.

But there is little doubt that Mr Monti did what was required in November 2011, which was to provide a new government to inspire international confidence and keep borrowing costs down, without the need for elections.

"Elections last year would have been extremely disruptive - it would have been a disastrous three or four months," says Mr Basagni.

"Monti provided a bridge solution, which was very useful - almost indispensable."

- Published10 December 2012

- Published10 December 2012

- Published10 December 2012

- Published9 December 2012

- Published8 December 2012