Italy tackles mafia-owned businesses

- Published

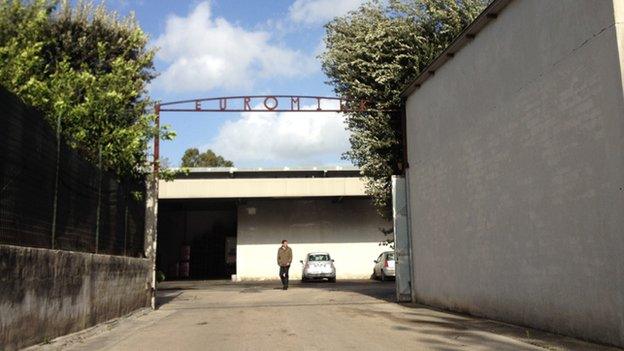

After being seized from the mafia, San Marcellino-based Euromilk was revived by the Italian authorities and it is now an economically viable enterprise

Sitting on the edge of a town outside Naples, the Euromilk dairy-produce distribution firm looks like any other small business engaged in a very ordinary trade.

But the compound, with its warehouse and offices, lies in the heartland of the formidable Neapolitan crime network, the Camorra.

And Euromilk, on the outskirts of the community of San Marcellino, used to be the property of mafiosi managers.

Now though, it is trying to shed its past.

This business is among many hundreds that have been seized from the mafia and put under the control of Italy's National Agency for the Management of Assets Confiscated from Organised Crime.

It tries to draw these firms away from their roots in the underworld, and sell them on to honest owners.

But only a tiny number of confiscated companies survive the complexities of that transition.

'Most wanted'

According to the agency, Euromilk was owned by a member of one of the toughest Camorra clans, the Casalesi.

Euromilk's caretaker manager, Giuseppe Castellano, says he was never afraid

The gang's leader, Michele Zagaria, was among the most wanted men in Italy until he was arrested last year.

He was captured hiding out in an underground bunker not far from the Euromilk compound.

"The company was confiscated because the person responsible for the firm was declared a member of one of the local clans," says Gianpaolo Capasso, the head of the Agency in the Campania region.

The fact that the business was in the hands of such a person was enough to warrant its seizure, whether or not it was operating illegally.

And after confiscating it, the agency put in charge a new, caretaker manager, Giuseppe Castellano, who has experience of taking over troubled or bankrupted companies.

So how did it feel, coming to assume control of an enterprise where the senior members of staff would have been used to working for the former, mafiosi boss?

"Of course they weren't happy," says the smiling, understated Mr Castellano.

"But I was never afraid. I tried to explain to them that there was a common interest, which was to keep the company running.

"I was also a bit lucky. I found people willing to help and thanks to that, the company is still here."

And the fact that the firm remains in business several years after it was seized is indeed a kind of victory.

Very often enterprises taken off the Mafia close down soon afterwards.

In the region around Naples the agency has confiscated about 300, but it has only managed to keep six of them running.

Corrosive idea

Ultimately, Euromilk should be sold to private investors

And that is a problem.

When the mafia sets up a firm, it creates employment. And too often when the state confiscates the asset, the company collapses and the jobs are lost.

"The state fires people, while the Camorra gives jobs," is a complaint the confiscation agency's officers often hear.

And this is exactly the sort of corrosive idea that the mafiosi would like to promote - the notion that in practical terms, communities might be better off with the gangsters than the rule of law.

So how does the agency try to get round this?

What does it do when it suspects that some of the most senior figures in the workforce of a confiscated firm are loyal to the former management, and might still have active mafia links?

"You know that if you fire those three or four key members of staff the company would shut down immediately, and all the workers would lose their jobs, including those who have no links," says Gianpaolo Capasso, the head of the agency in the Campania region.

"So we chose to allow these people to stay, closely controlling their activities, trying to limit any illegal activity on their part."

But Mr Capasso says that in the end, when the agency was about to sell off a firm to a new owner, those members of staff believed to have mafia connections were forced to quit.

He says that in the specific case of the confiscated Euromilk Slr firm in San Marcellino, if it is sold, some employees will be fired.

Corruption and intimidation

Mafia bosses involve themselves in apparently legitimate business activity for different reasons.

For a start it is possible to make good money out of a busy company in, for example, the construction industry.

And that can be especially true if you bring to bear the "business ethics" of the mafia, such as intimidating competitors, or corrupting the local officials who hand out contracts.

At the same time, a superficially legitimate business can be used to launder money made in criminal activity, such as drug trafficking.

A mafia boss's children or other relatives might need access to money that at least looks as if it has been earned in a conventional manner.

So having a foot in the world of legality can be useful for the mafiosi in various ways.

And the agency says there are mafia strongholds where the local business environment is so polluted by the presence of gangster-run enterprises that it is almost impossible for honestly managed firms to operate.

To take just one of many possible scenarios, a legitimate company might be forced to pay protection money to the local mafiosi.

But a competitor in the area, a firm run by the gangsters themselves, would obviously not be subjected to that kind of cost.

Wealth and prestige

Asset confiscation agency spokesman Dario Caputo says some communities in southern Italy, where the mafia is particularly strong, appear lawless

A Rome-based senior spokesman for the agency, Dario Caputo, says "there definitely are extremely difficult situations in which the social tissue is so damaged, the conditioning [by the mafia] is so strong, that there is a feeling that one lives in a different reality, outside legality".

"We see this difficulty in small towns in some areas of the south," he says.

But despite the many difficulties, Mr Caputo sees the confiscation of assets as an essential part of Italy's struggle with the Mafia.

He says: "What hurts the mafiosi most is not only going to jail for a certain period, it is also losing their wealth.

"Because this is what gives them prestige, makes them feel important in the eyes of common people."