Hugo Chavez leaves Venezuela in economic muddle

- Published

Hugo Chavez had an impulsive approach to the economy

One of the most damning verdicts on the late Hugo Chavez's leadership of Venezuela came from a doctor who made a name for himself by claiming to have inside knowledge of the cancer that eventually killed the president.

Dr Jose Rafael Marquina, a Venezuelan based in Miami, repeatedly predicted that Mr Chavez's illness would prove terminal, providing detailed accounts of what he said was the president's course of treatment.

His statements were given extensive coverage by the opposition media in Venezuela, eager to fill the vacuum left by the lack of official information about Mr Chavez's condition.

But whatever the truth of Dr Marquina's medical diagnosis, his broader criticism of the president's record hits home. As he said during an interview with the Tal Cual newspaper in December 2012: "Chavez dealt with his illness the way he dealt with the country - in an improvised fashion."

That habit of impromptu policymaking was integral to Mr Chavez's style, right from the start of his 14 years in power.

Time and again, the president would make major decisions on an ad hoc basis, often during the course of his rambling and unscripted weekly TV broadcast to the nation, known as Alo Presidente.

He was particularly prone to quick-fix solutions in economic policy, resorting to regular currency devaluations, expropriations of private firms and inflation-busting public-sector pay rises rather than tackling the economy's underlying structural problems.

This fire-fighting approach continued even as Mr Chavez lingered on his Cuban sickbed, with Vice-President Nicolas Maduro implementing a 32% devaluation of the bolivar in February.

As a result, Mr Chavez bequeaths a nation beset by crumbling infrastructure, unsustainable public spending and underperforming industry.

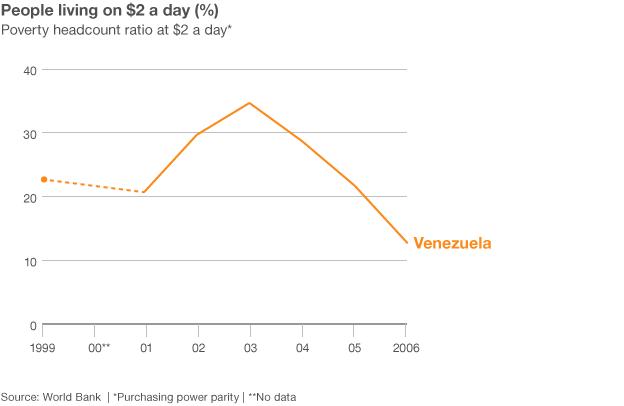

Thanks to his social programmes, poorer Venezuelans have certainly benefited from the country's oil wealth more than they did under what he called the rotten elites that used to be in charge.

But there are strong suspicions that much money has been wasted - not just through corruption, but also sheer incompetence.

Are you better off than in 1998?

During Hugo Chavez's time in office, from 1999 to the present day, income inequality in Venezuela gradually declined, as it did in most of the region.

The country now boasts the fairest income distribution in Latin America, as measured by the Gini coefficient index.

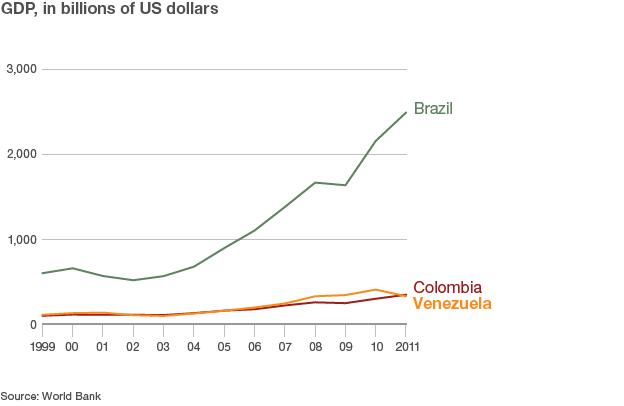

Brazil's economy has grown faster than Venezuela's

In 2011, Venezuela's Gini coefficient fell to 0.39. By way of comparison, Brazil's was 0.52, in itself a historic low.

So every Venezuelan now has a more equal slice of the cake. The trouble is, that cake has not been getting much bigger.

"Venezuela is the fifth largest economy in Latin America, but during the last decade, it's been the worst performer in GDP per capita growth," says Arturo Franco of the Center for International Development at Harvard University.

As Mr Franco says, it depends on how you measure Venezuela's progress.

If you compare life under Mr Chavez with the previous 20 years, under a now discredited two-party system widely blamed for rampant corruption, the Chavez era is preferable.

But if you look at the superior economic performance of neighbouring Brazil and Colombia during the same period, it suddenly doesn't look so rosy.

And given that the price of a barrel of oil is now roughly 10 times what it was when Mr Chavez was first elected, his opponents say that he could and should have done more.

Venezuela's economy: Oil takes the strain

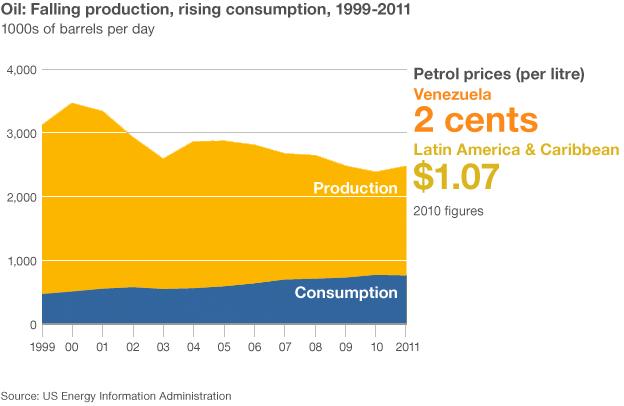

Mr Chavez's failure to diversify Venezuela's economy means that oil is still its mainstay. In fact, it accounts for more than 90% of the country's foreign currency inflows.

About 50% of government revenues come from the petroleum industry, mostly from state company PDVSA.

The Amuay fire raised questions about investment in Venezuela's oil sector

Mr Chavez's government took firm control of PDVSA in 2003, when it fired 40% of the workforce in the aftermath of a general strike aimed at forcing him from power.

But critics have accused the firm of neglecting maintenance while it funnelled oil revenue into government social programmes, especially after an explosion in August 2012 at the Amuay refinery, the country's largest, in which 42 people were killed.

Instead of investing in PDVSA to increase production, Mr Chavez treated it as a cash cow, milking its funds to finance his social spending on housing, healthcare and transport.

Finding out just how that money has been dispensed is not easy. But the government has become steadily more involved in every sector of the economy, to the detriment of the private sector.

In September 2012, Reuters news agency published a special report, external into a state corporation, Fonden, that now accounts for one-third of all investment in Venezuela.

It found a string of abandoned or half-built facilities, including a paper factory, an aluminium mill and a fleet of unused buses - all of which apparently received money from Fonden.

Fonden has absorbed $100bn of Venezuela's oil revenues since it was founded in 2005.

At the end of January, the government cut PDVSA's contribution to Fonden by 19%, a move which seems to presage a round of public spending cuts. But until the post-Chavez political landscape is clearly established, the president's successors can hardly afford to alienate the people with austerity programmes.

Public spending: Can the boom last?

In the run-up to his presidential election victory last October, Mr Chavez made low-income and social housing a priority, launching a plan to build three million homes by 2018.

Mr Chavez stepped up house-building in the run-up to the election

The housing drive fuelled big increases in public spending - and big expectations among those yet to be housed under the programme.

According to Bank of America-Merrill Lynch, government expenditure rose 30% in real terms as a result over the 12 months leading up to the election.

But all that largesse took its toll on the public finances. Capital Economics, a research company, estimates that Venezuela's fiscal deficit widened to 9% of GDP in 2012, while Morgan Stanley reckons it could have reached 12% by now.

According to the World Bank, the Venezuelan economy is estimated to have grown by more than 5% during 2012. However, it forecasts a slowdown in 2013, with just 1.8% growth expected, while many analysts are expecting the country to fall into recession this year.

The latest maxi-devaluation of the Venezuelan currency will help the government's financial position. Since oil is priced in dollars, a weaker bolivar increases the local value of oil revenues, giving the government more cash.

In theory, it should also help Venezuela to export more goods from other sectors of the economy. But observers reckon the country's manufacturing sector is too small to benefit much - another consequence of Venezuela's concentration on oil to the exclusion of all else.

In the words of Michael Henderson at Capital Economics: "The current malaise is the product of years of capital flight and under-investment, which has hollowed out the country's productive base."

Borrowing against oil

So how did the government finance its pre-election spending spree? Foreign private investors have certainly stayed away since Mr Chavez's nationalisation drive began.

High inflation, still nudging 20% a year, doesn't help either.

Will the Venezuelan capital see brighter times ahead?

As survey organisation Consensus Economics says: "Soaring inflation and government spending - coupled with currency and capital controls - have created a widening fiscal deficit.

"The authorities are increasingly reliant on external debt to finance this."

For "external debt", read loans from China. According to Bloomberg news agency, the state-run China Development Bank has lent Venezuela $42.5bn over a five-year period.

Oil Minister Rafael Ramirez said in September 2012 that of the 640,000 barrels of oil a day that Venezuela exports to China, 200,000 went towards servicing the country's debt to Beijing.

Unless PDVSA's underperformance can be remedied, those debts will remain and will probably grow as the country's gap between spending and income widens.

The impact for the region

It certainly doesn't seem hard to uncover evidence of waste in government expenditure during the Chavez years.

But the overspending doesn't stop at home. In an effort to spread the influence of his Bolivarian revolution, Mr Chavez allowed Cuba and other countries in the region to benefit from cheap deals and soft loans under the Alba and Petrocaribe programmes.

The next administration will have to decide whether or not to continue funding that extensive network of petro-diplomacy.

In the meantime, most countries in the Caribbean, already suffering from a decline in tourism because of the global economic downturn, will be hoping that Venezuela's economic lifeline is not about to disappear.

Tackling poverty and increasing access to education and healthcare were avowed aims for President Chavez

Income inequality has dropped in Venezuela but GDP growth has been poor

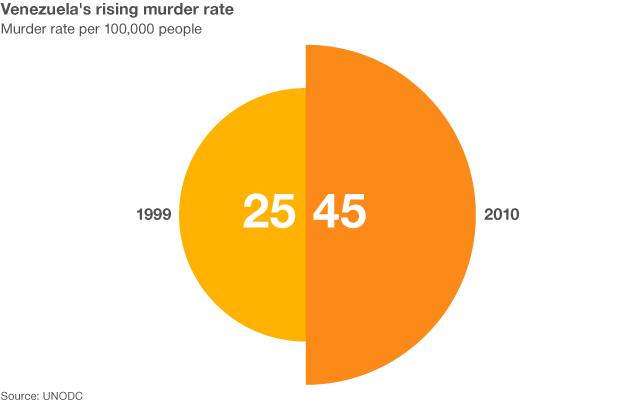

The high rates of murder, other violent crimes and kidnappings are key concerns for Venezuelans

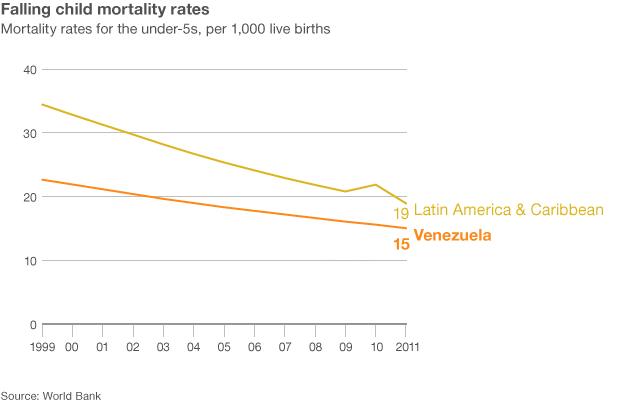

Child mortality rates fell, in line with the region, but some medical staff protested at lack of investment

Venezuela's oil wealth has been the mainstay of the economy, providing 50% of government revenues