Governments urged to prepare for the worst

- Published

Events trigger events, and responding to crisis means policy makers often do not deal with long-term risks

Governments should learn from companies and appoint dedicated "risk ministers", according to the authors of a World Economic Forum (WEF) report.

The "ministers" should assess a broad range of economic, environmental, geopolitical, societal and technological risks, the Global Risks 2013 report, external's authors reason.

Companies have long had their own "finance ministers", though they call them chief financial officers, and in recent years it has become common to also have risk management functions in companies, according to Axel Lehmann, himself a chief risk officer at Zurich Insurance and a co-author of the report.

It would be useful, adds Lee Howell, managing director of the WEF's Risk Response Network and editor of the report, if governments were to create similar functions, with a view to "take an interdisciplinary and holistic approach to risk".

"How often do you see a central bank governor talk to a defence minister?" he says. "It doesn't really happen."

Multiple risks

The risks faced by nations - indeed by the world - have always been both complex and interconnected.

But recently, "the changes are in the amplification and the speed of these interconnections", according to David Cole, chief risk officer at the reinsurers Swiss Re and co-author of the report.

The complexity arises partly from the extensive variety of risks. The WEF report identifies the major risks of concern globally:

Health and hubris, the basic idea of which is that the world is complacent about threats to global health, ranging from rising resistance to antibiotics, to the way pandemics could easily spread in a hyperconnected world. In a world where genetic mutation often outpaces human innovation, it is foolhardy to be complacent, the report's authors suggest.

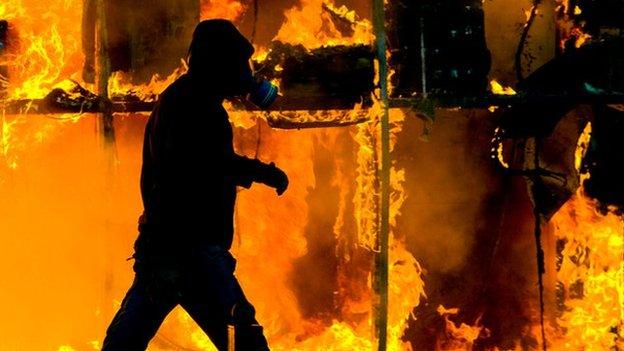

Economy and environment under stress, which focuses on how the economic and the environmental storms are colliding, essentially relating to how - during a period of widespread austerity - it is difficult to mobilise finance and other resources to mitigate risks arising from climate change, such as extreme weather events. The cost of storm and flood damages are huge and growing, and governments are finding it increasingly hard to pay. Other risks relate to socioeconomic or geopolitical fallouts from greater gaps between rich and poor, or from persistent global economic fragility. Violent anti-austerity protests in Athens might be little more than mild examples of such risks.

Digital wildfires are risks relating to how "the democratisation of information can... have volatile and unpredicted consequences, as reflected in the riots provoked by an anti-Islam film on YouTube", the report notes. Confidence in governments and companies, newspapers and markets, can be eroded by fast-spreading information or propaganda.

But these are just three of the 50 risks described by the report, ranging from security risks such as terrorism or the militarisation of space, to more existential risks such as shortages of food and water.

Governments should pay more attention to the risks that might lie ahead and prepare accordingly

"Some of the risks we see are not acute, but that doesn't mean they're not important - in fact, many of them are chronic," says Mr Cole.

The fact that there are not just so many risks, but also that they are in constant flux - responding to each others by morphing into new risks that in turn change other risks - means responses need to be fluid and flexible too.

Or more to the point, nations should not merely respond to crisis once it has happened, but instead work out how to "build resilience to global or external risks", by dealing with it the way they do with "preventable" risks such as breakdowns in processes, or "strategic risks" that are weighed up against potential rewards, Mr Howell says.

Nations' ability to respond and recover, he reasons, will rely on their ability to set aside excess capacity and back-up systems that kick in during times of crisis. It will rely on their resourcefulness and their robustness. Risks must be assessed in advance, both in terms of how likely it is that events will happen, as well as by looking at the likely impact of such events.

'Profound implications'

The report also describes so-called X Factors, or "unintended consequences of technology or science", according to the chief editor of Nature Magazine, Tim Appenzeller, who lists five such risks:

Runaway climate change, or the uncertainty about the consequences if we have passed the point of no return. "What if we have already triggered a runaway chain reaction that is in the process of rapidly tipping Earth's atmosphere into an inhospitable state?" the report queries.

Significant cognitive enhancements, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation that help boost memory - offering a number of obvious benefits, while at the same time posing risks ranging from unknown side-effects to ethical considerations around the impacts of the pills akin to those associated with doping in sports.

Rogue deployment of geoengineering, such as the creation of sun shades by injecting small particles high into the atmosphere to block some of the incoming solar energy and thus reduce global warming, a process that could inadvertently cause droughts. "The global climate could, in effect, be hijacked by a rogue country or even a wealthy individual, with unpredictable costs to agriculture, infrastructure and global stability," the report notes.

Costs of living longer, which in a sense could be seen as an unintended consequence of developments in medical science, in that "big inroads against common banes such as heart disease, cancer and stroke, may be in the offing". "Are we setting up a future society struggling to come with a mass of arthritic, demented and, above all, expensive elderly who are in need of long-term care and palliative solutions?" the report asks.

Discovery of alien life is the final X Factor risk, with the report suggesting that "it is increasingly conceivable that we may discover the existence of alien life or other planets that could support human life". It talks of "profound implications" of such a discovery and insists it "would fuel speculation about the existence of other intelligent beings and challenge many assumptions which underpin human philosophy and religion".

Action is necessary

Identifying risks might well be the easy part, however. Working out what to do about it, and then doing it, might turn out to be much trickier, but there is no way around it, according to Mr Cole.

"Our responsibility as leaders and as communicators in society is to leverage this awareness into action," he says.

"We cannot keep kicking the can down the road.

"By delaying action, we're not avoiding the problems, were just making it more expensive, not just in economic turns but also in terms of lives."

The Global Risks 2013 report, external was developed from an annual survey of more than 1,000 experts from industry, government, academia and civil society. It was published ahead of the World Economic Forum's annual meeting in Davos from 22-27 January.