HMV leaves social gap in High Street

- Published

For some, the last reason left to go shopping

For anyone of a certain age, the collapse of music retail chain HMV poses one immediate and pressing problem: where do you spend time on the High Street once the last place worth browsing in has gone?

Men reluctantly dragged round shopping centres by their partners have traditionally sought refuge in the nearest record shop or bookstore.

But with both those kinds of physical media now being rapidly replaced by digital equivalents, the attractions of a trip to the shops have dwindled further.

Nick Twine, a 47-year-old supervisor at home improvement chain B&Q in Lincoln, probably speaks for many of his kind when he laments the changes at his local HMV shop.

"My time to go to the High Street is to take the kids shopping," says Mr Twine, who has three daughters. "They want to go to the shops and buy clothes and make-up. HMV is my soother to the pain of going to the shops - I can spend a couple of hours browsing around."

The problem is that browsing is all he does there nowadays. The chain's decision to stock fewer music titles in favour of games and gadgets has made it hard for him to find any CDs worth buying.

"I have broad music tastes - anything apart from opera - but I went there on Sunday with £50 to spend and I actually couldn't find anything that I needed.

"It's kind of indicative that they can never carry enough stuff to appeal to guys like me, who have vast record collections and go online to find the stuff they need."

Failed turnaround

That observation goes to the heart of why HMV is in such deep trouble. As a shop that began as a seller of recorded music, it has made concerted efforts to branch out and widen its product range in recent years.

However, it has struggled to persuade people to make it their first port of call for buying their iPads and designer headphones, while DVDs and computer games are performing as sluggishly as the CD market.

HMV is having a miserable time

As a result, HMV has managed to alienate its core market of CD-buyers, while failing to attract new customers for other products, leaving it in the worst of all worlds.

Other efforts to turn around the business, such as moving into the live music market, have also failed. London music venues such as the Forum in Kentish Town and the Hammersmith Apollo were sold off last year, following the Waterstones book chain, which was spun off in 2011.

In recent times, HMV has been propped up by the record industry, which is dismayed at the idea of losing the last dedicated music retailer on the High Street.

The record labels, film companies and games firms that supply it with stock were persuaded to take a small stake in HMV as the chain found it increasingly difficult to pay them for the merchandise.

However, it was a call for further investment, to the tune of £300m, that proved to be the last straw.

Of course, HMV has done well to keep going as long as it has, given how many of its rivals have fallen by the wayside.

It has been visibly struggling since 2007, when it announced the first of its attempts to revamp the business. But during all that time, it managed to avoid going the way of other vanished music retailers such as Tower, Virgin, Our Price and many more.

"It has been a long time coming," in the words of Neil Saunders, managing director of retail consultancy Conlumino.

On the other hand, as he continues, "everyone has known that the writing was on the wall since the day someone first downloaded a digital song."

Niche business

Another reason for HMV's downfall came home to me not long ago when I visited my local branch in Croydon.

Over the past few years, record companies have been trying to halt the march of Apple's iTunes digital music service by making physical CDs a more interesting purchase.

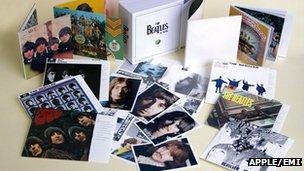

They have created "super-deluxe" versions of classic albums by big-name artists, usually multi-disc box sets including vinyl or DVD extras and typically retailing at £50 to £150 or even more.

Luxury music box sets are hard to come by at HMV

With many record industry observers warning that record shops could soon be as rare as blacksmith's shops or candle-makers', this has proved a worthwhile way of catering to a hardcore audience of music fanatics, rather than chasing a fast-declining mass audience.

The problem is that these instant collector's items are seldom seen in the shops. When I asked an assistant in one branch of HMV where the box sets were, he replied that I would have to go to their central London shops: "We've moved all that to the Trocadero now."

The store was, of course, piled high with discounted copies of big-selling CDs, much as can be found in any supermarket. The only option was to trudge home, order that prized item on Amazon and hope it wouldn't get too dented in the post.

The record industry can clearly adapt if music retailing becomes a niche market, as shown by the way it has embraced the vinyl revival. However, HMV has not been in sync with that strategy: it has chosen to stand or fall as a mass-market retailer.

Back in Lincoln, Nick Twine is still digesting the implications of that. "When I was growing up, record shops were the place to go.

"I grew up in a small town with three record shops. Now I'm going to be living in a medium-sized town that has none."