Q&A: World Economic Forum, Davos

- Published

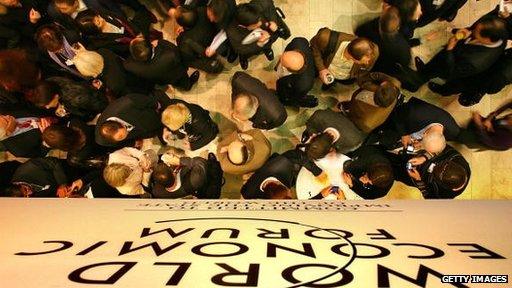

Once again the rich and powerful are congregating in Davos, Switzerland, for the annual meeting of the World Economic Forum (WEF) - but does the forum still have a purpose?

The WEF is a talking shop. Arguably, though, it is the best of its kind in the world.

The concept dates back to the early 1970s, and is very simple: Take top business leaders out of the pressure-cooker of their jobs and bring them together in a remote valley in the Swiss mountains. Removed from their daily routines, they can freely exchange ideas - and maybe do a deal or two.

Professor Klaus Schwab, who started WEF and still runs the event, calls it "a platform for collaborative thinking and searching for solutions, not for making decisions".

Over the years it has evolved, taking in artists, politicians of all stripes, activists from trade unions and campaign groups, social entrepreneurs, inventors, all sorts of clever people from universities and think tanks, and young entrepreneurs.

How big is it?

What started as a cosy chat around the log fire in a mountain chalet is now a huge event, with more than 2,500 participants from 140 countries, hundreds of journalists, about 40 heads of state, and numerous other politicians.

The key ingredient, though, is the 1,500 bosses of many of the world's top companies - not just from the West, but from emerging economies as well.

And this is just the annual meeting, traditionally held in the Swiss mountain village of Davos.

The once-a-year event has evolved into a year-round succession of regional forums in all parts of the globe, plus a bevy of working groups bringing together key decision makers on global issues such as cyber security, global risk, and fighting corruption and poverty.

All these activities are supposed to underpin the forum's official motto: "Committed to improving the state of the world".

And I thought it was just a bunch of capitalists having a good time in the mountains...

Well, that's one way to see it. Yes, Davos is about the rich and the powerful having a good time. The parties and exclusive dinners, the deal making and schmoozing - and the skiing - are legendary.

And the exclusivity of the event has offered fertile ground for plenty of conspiracy theories. But Davos is decidedly not a place from which the world is run.

Still, with so many powerful people in one place, Davos has often been targeted by the Occupy movement, following in the footsteps of Occupy Wall Street and Occupy London Stock Exchange. There have even been topless protests from the Ukrainian feminist group FEMEN.

But you have to give the forum's organisers some credit: every year they are trying hard to put tough topics on the agenda and add inconvenient voices to the mix. Fighting poverty, climate change and the shortcomings of banks and companies are always big themes here.

Also remember that the forum often provides the cover for political enemies to meet, gain mutual understanding, and even strike a peace deal.

And then there is the fabled "Davos consensus", when a common theme emerges that sets the global agenda for the months to come.

What are this year's big topics?

It's always hard to tell but there's bound to be lots of discussion about the plunging price of oil, the outlook for Russia and cyber security. There are also several debates organised around finding a cure for Ebola and "mindfulness" in business.

There's always lots of interest in the latest technological developments and what challenges and opportunities they could create for businesses.

How does it work?

A couple of years ago fruit smoothies were handed out with little woolly hats on

It is obviously big, and in a strange way it is both free-flowing and utterly regimented. The fairly rigid framework is provided by hundreds of official sessions - panels, speeches and workshops - ranging from keynote speeches from the German chancellor Angela Merkel, France's President Hollande and China's Premier Li Keqiang, to a bunch of Nobel Prize-winning economists discussing the year's economic challenges, to a panel discussing how video games are affecting the next generation.

The free-flowing is everything in between. There are numerous private sessions and bilateral meetings. The corridors of the concrete-and-wood confection of a conference centre are host to constant networking and schmoozing.

Here you can hear financial regulators harangue top bankers, trade unionists challenge the bosses of the world's biggest multinationals, and the finest minds in economics discuss the finer points of quantitative easing.

Security is always a big issue in Davos

And what will be the outcome?

Don't expect any. Not even the organisers do. They say that's not the forum's purpose.

But if participants go away with new ideas, new connections, a better awareness of the world around them, and fresh ideas on how to tackle its problems, Davos may well have served its purpose once again.