Girls and women 'hit the hardest' by global recession

- Published

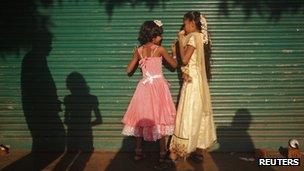

Girls are "the largest marginalised group in the world", says one of the report's authors

Women and girls were hit the hardest by the global recession, according to child rights and development organisations.

"The world is failing girls and women," a report by Plan International and the Overseas Development Institute said.

A shrinking economy sent girls' infant mortality soaring, and more females were abused or starved, they said.

This could erode gains made in recent years towards reaching the Millennium Development Goals, they added.

"The improvements made during the last five years are very fragile," Nigel Chapman, chief executive of child rights organisation Plan International, told BBC News.

"It is shocking, because I don't think anyone's really noticing it."

Dying babies

The problems started when the girls were very young, Mr Chapman explained.

"Girls are the largest marginalised group in the world," said Mr Chapman.

The proportion of baby girls who died when the economy shrank rose five times faster than the proportion of baby boys who died, he said.

Hence, a 1% fall in economic output increases infant mortality by 7.4 deaths per 1,000 girls against 1.5 for boys, said Mr Chapman, citing World Bank research into previous crisis in 59 countries., external

"It's the most stark example of the impact of exacerbated poverty," said Mr Chapman.

More work, less food

The report, which draws on evidence from a wide range of sources such as academic studies or papers published by the World Bank, points out that there is a lack of data gathered specifically to measure impact based on gender.

"However, from what is available it is clear that girls and young women are at specific risk during periods of economic uncertainty and stress," the report stated.

As the recession caused poverty to spread, older girls were increasingly taken out of school, says the report.

Primary school completion for girls fell 29% whereas for boys it fell 22%.

Many girls were taken out of school to help out at home because their mothers had to work longer hours for less pay, the report found.

"Girls get sucked into domestic chores," said Mr Chapman. "And once they stop going to school it's very hard to get back into the rhythm of things."

In many cases, an increase in the number of child marriages was observed once the downturn hit. "Poverty-struck families simply could not afford to feed those mouths, so they'd marry them off early," said Mr Chapman.

The report warns that the global recession means more girls miss out on school

Others were sent out to work as child labourers - sometimes as sex workers.

At home, girls and women would often eat less to make sure the main "breadwinner" had enough to eat, so the levels of food shortages and malnutrition were more common among girls than boys, with women often making even greater sacrifices for their children.

"They got weaker and less healthy," said Mr Chapman. "They got into a downward spiral."

Meanwhile, girls and women suffered more neglect and abuse than they did before the economic downturn.

Or when pregnant, they received less help than previously, leaving girls between 14 and 19 particularly at risk of death in pregnancy, the report said.

Create jobs

Girls and women also experienced reduced access to basic services and social safety nets, it said.

"Girls' fundamental human rights are increasingly under threat," said one of the report's authors, Nicola Jones, research fellow at the Overseas Development Institute.

Much of the problem lies with "entrenched gender inequality", according to Mr Chapman, though current challenges such as austerity budgets and long-term economic trends.

To solve the problem, international programmes must be set up to ensure young women are properly fed, to protect them socially, to make sure they get to go to school and to create jobs for them after they have finished their education, the report recommended.

"We must close the gap between girls and women on the one hand and boys and men on the other," said Mr Chapman.