Davos Man eyes investment opportunities

- Published

Does Jorn Madslien's team win the competition?

I have seen the future - the Indian consumer will be crowned king and our $1bn (£630m) bet will grow tenfold in a decade.

It started as a vision, hammered out by our team of international investors.

"You've all seen the Indian tourism campaign 'Incredible India'," declared one of our members.

"We don't need an incredible India, we need a credible India."

And so our fund was born - Credible India Consumer Fund.

Secretive investors

Credible India was one of eight funds launched as part of a fantasy investment event at the World Economic Forum's annual meeting in Davos.

The rules of the Investment Heatmap game are simple:

Eight teams get to invest $1bn each.

Each team is allocated one geographical region and one industry.

The goal is to pick winners or if in doubt go short - that is, using financial instruments that mean you gain when investment values fall.

"It is partly real, partly game," said one venture capitalist as it all kicked off.

Chief executives of some of the world's largest industrial groups were up against hedge fund managers with tens of billions of dollars under management.

Corporate acquisitions executives teamed up with venture capitalists, private bankers with savvy entrepreneurs.

One player claimed to be a former CIA agent, though that might have been a joke. In Davos, as in the world of investments, it is not always easy to distinguish fantasy and reality.

But one thing was made clear: names and faces were secret. Like Vegas, what happens in Davos stays in Davos.

A strategy is born

Teams were formed at break-neck speed and soon the room was buzzing.

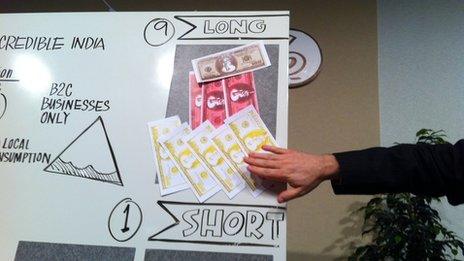

The participants in the game had pretend money with which to invest

"For tech, we'll go after the bottom of the pyramid in India," said one investment strategist.

"Tobacco and alcohol companies are going long," chipped in a venture capitalist.

"Semi-urban and urban is where we'll be; that's where the growth will come," a fund manager called.

And then, a word of caution from a banker: "But you can't just do early stage investment with a billion in India. There aren't enough deals available."

And so, in just 20 minutes, Credible India's strategy was born.

Name dropping

The next step in the game was designed to figure out which of the eight investment strategies was the one most likely to be successful.

Each team was told to explain their strategies to the others, who would then chose which ones they liked the most. Everyone was given cash to invest and the only rule was that no-one could back their own fund.

The average Davos delegate is not short of a few dollars to invest for real

"I'll do the presentation," said our team's fund manager.

A series of sessions followed, fuelled by testosterone and alpha male posturing worthy of the calibre of the characters in the room.

Some funds tried to impress by dropping names of respected economists or business people.

"We've got Prof Robert Shiller working for our fund," bluffed one, while another claimed: "Carlos Slim's family and others of similar stature are involved."

The Chinese consumer fund boasted of a chief executive in its team who had promised to quit his job in industry and move with his family to China, where he would start up a rival to his current employer.

"It won't be with my current family," the chief grinned, only for the pitch to be changed to reflect how he would be "moving with his new wife" instead.

The Africa fund claimed to have a successful serial entrepreneur on its team, but declined to give away too much. "I'm not going to tell you exactly what we're going to do," said a secretive hedge fund manager.

"I would not like a fund that tells you everything, 'cos it changes every day."

"We feel aerospace and defence is at a crossroads, and we're not going to cross," reasoned one speculator. "The peace dividend is good for the world, but not for the industry."

Real estate offered a golden opportunity, according to the European Renaissance Fund, not because it would rise in value any time soon, but rather because "a lot of existing portfolios will be offloaded by distressed investors".

Smooth professionals

One fund, which dubbed itself "A Berkshire Hathaway Fund" - which in the real world is controlled by investment guru Warren Buffett - decided to invest $900bn in low-yielding but ultra-safe government securities "with a healthy sidepocket" that would ensure the investment wasn't pulled before maturity.

The funds used white boards to work out their investment strategies

The remaining $100m would go into "highly leveraged shorts" in Russia - meaning bets that would make money if asset values in Russia were to fall sharply.

"But we'll go long in Russian cement, so that if we'll end up under it, at least it's our cement," quipped one investor.

One financial rocket scientist talked about using financial derivatives to hedge against "air pockets along the way", another said no fees would be incurred and insisted his fund was "not looking to generate returns through financial engineering".

And so the presentations went, delivered professionally and confidently by smooth professionals who had clearly seen it all before.

Not that easy

In the end, Credible India's insistence that per capita spending power is set to double, that 50% of the population has yet to turn 25, and that 365 million people are set to enter the workforce over the next 15 years helped win over many in the room.

So in the end, our fund raised more money than any of the others and we were declared winners.

Reflecting on the evening, one investor lamented: "If it had been that easy, somebody else would've done it already."

And yet, insisted another, many of the predictions voiced during Investment Heatmap sessions in Davos will be mirrored in the real economy during the following year or years.

If only I knew which ones they were.

You can follow Jorn's coverage from Davos on Twitter @jornmadslien., external