TV's white spaces connecting rural Africa

- Published

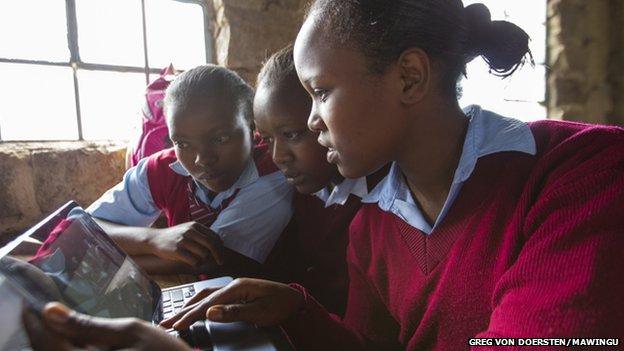

Wide open spaces: Projects like the one in Nanyuki could let people in the more remote areas connect to the internet

"This is the greatest achievement I can say for this school. [The students] are finding it a great favour that they should be the first school in Africa to have this kind of a project. It is very exciting. They wonder how they got there."

Beatrice Nderango is the headmistress of Gakawa Secondary School, which lies about 10km from Nanyuki, a market town in Kenya's rift valley, not far from the Mount Kenya national park.

The school is situated in a village that has no phone line and no electricity. The people that live here are mostly subsistence farmers.

"We don't really have a cash crop, but the farmers do a bit of farming," says Mrs Nderango.

"They grow potatoes, a little bit of maize, but we don't do well in maize because of the wild animals. They invade the farms."

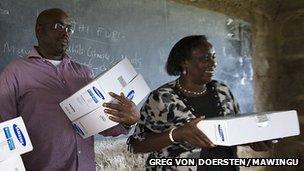

Going online: The schools are being supplied with computers as part of the project

Although Kenya has fibre optic broadband thanks to the Seacom cable, external, most of rural Kenya is not connected and until now getting online would mean travelling to town.

But all of this is changing, thanks to technology that uses the unused parts of the wireless spectrum that is set aside for television broadcasters - the white spaces.

The colour of television

The project is part of the 4Afrika Initiative, an investment programme being announced by technology giant Microsoft, that also includes a new Windows Phone 8 smartphone for the region and investment in help for small businesses on the continent, and in education and internships.

The base stations work in the same way as mobile phone masts, and will create massive wifi hotspots

For the white spaces project, the company is working with a Kenyan ISP, Indigo Telecom, and the Kenyan government.

The ISP is installing wireless 'base stations' - or masts - that are solar-powered, to get round the lack of mains electricity.

The base stations act as a link to the nearest main cable connection to the internet, without the expense of extending the fibre-optic network.

The solar panels will power the bases stations - and also charge computer equipment

The signal supplied is much more powerful than normal wifi.

"What we are calling TV white space, that is just a different set of frequencies. It is between 400 megahertz and about 800 megahertz, and those radio frequencies will just go further," says white spaces expert Professor Robert Stewart of Strathclyde University.

"They can go through walls, they will kind of bend around hills, they will give you much better connectivity. And of course, that's why the TV guys chose that in the first place."

Local schools, a healthcare clinic, a government agriculture office and a library have been connected in the first part of the pilot.

Ms Nderango says internet will benefit teachers and students alike.

"Students will now be introduced to e-learning, they will be able to carry out the assignments, they'll be able to do a lot of research," she says.

"To add to that, there is the exposure to the rest of the world."

And she believes the wider community will benefit as well.

"It will change lives, because on the internet you can access information about skills.

Beatrice Nderango (right) says the new computers will make teaching easier

"The farmers for example will improve their skills, and learn entrepreneurship."

Business networking

Microsoft's Fernando de Sousa says getting rural areas online is a crucial part of making them economically viable.

"There is... a commercial responsibility that both private and public sector have across Africa to bring technology and bring access that can then drive economic growth, economic development and sustain employability, especially outside of the metropolitan areas," he says.

"It is going to significantly increase the ability for innovation and the great ideas that Africans have to actually reach markets and become available for use by consumers... I think that there is a fantastic opportunity for Africa to showcase its own capabilities in the world because of the increased access."

The local healthcare clinic will be part of the network, opening up access to telemedicine resources

The next step is to open the network more generally to the business community in the area.

"The commercial viability of actually deploying white spaces on a broad spectrum across the communities, is something that is very important... because a. it can't be a subsidised service; and b. it is not a private government or community network," says Mr de Sousa.

"It really needs to be a commercially viable network. Bringing small businesses online and enabling them to use the technology is very, very important."

This is not the first time that TV white spaces have been used in this way - in the UK pilots are underway on the Isle of Bute in Scotland and in Cambridge.

In the United States, Wilmington, North Carolina, has a white spaces project in place, and the Air.U partnership, external hopes to connect rural college campuses. There are several test beds around the world.

More is planned. In Africa, Google is sponsoring a project in South Africa, external that will connect 10 schools in the Western Cape for six months, that will launch soon.

There are obstacles: in many countries this part of the spectrum is licensed, and the way it is used is changing as television services move to digital. National and international regulators are looking at how to allocate space, to avoid having competing services trying to use the same space.

For now, and probably in the long term, TV white space networks will be complementary to fibre-optic broadband rather than a replacement. But Strathclyde University's Prof Stewart, one of the men behind the pilot on the Isle of Bute, thinks that for remote rural areas it may be the most cost-effective option.

"If we find that rural communities in developing or developed countries can access this without significant expense, then it will make a difference," he says.

"It is not going to solve all the problems. It is not for everyone. But it will solve problems for some folks."