Lance Armstrong: Fuller fights to fix cycling's doping culture

- Published

Usada said Armstrong ran the most successful doping programme in sport

The major sport story of the past six months has been the fall from grace of cyclist Lance Armstrong for extensive doping offences, and the subsequent stripping of his seven Tour de France titles.

It is the latest debilitating blow to a sport that over the past decade, if not longer, has become increasingly synonymous in the public mind with drug taking.

Despite previous scandals, many inside and outside the sport recognise the Armstrong case has been a watershed moment, and in December a pressure group of former cyclists and others in the industry was formed to demand radical reform of the sport's anti-doping approach.

Called Change Cycling Now (CCN), the driving force behind it is Jaimie Fuller, chairman, and until last year chief executive, of sports compression-wear firm Skins.

He says he launched CCN because of the sluggish response of world cycling body the UCI to the report by the US Anti-Doping Agency (Usada) into Armstrong's drug regime.

Usada labelled Armstrong a "serial" cheat who led "the most sophisticated, professionalised and successful doping programme that sport has ever seen".

Do It Yourself

"The media was going gaga, all hell was breaking loose, and I was waiting for the UCI to do something, but nothing happened," says Mr Fuller, whose firm, based in Steinhausen, Switzerland, has sponsored cycling for the past five years.

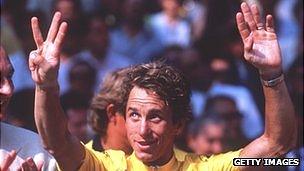

Greg LeMond, a leading light of CCN, remains the only US winner of the Tour De France

Just over a week later, the UCI accepted the findings and sanctions of the Usada report.

But Mr Fuller says this was inadequate in light of the damage that had been done to the sport over many years, and something more had to be done to prevent a repetition.

"I sat back waiting for someone else to do something, and they didn't, so I thought… I will do it myself," he says.

After a lot of phone calls he had enough people involved, including former riders - most notably three-times Tour winner Greg LeMond, journalists, anti-doping experts, and others from within the cycling industry.

Charter for cycling

Funding to get CCN off the ground came from Mr Fuller's own pocket. However he is at pains to point out that this "coalition of the willing" is not a Skins-led organisation, or some sort of publicity stunt.

"My aim was to bring together as many different stakeholders as possible," he says.

"At our first meeting, we came up with four outcomes that we want to see, that are incorporated in our charter."

These call for a "truth and reconciliation" committee to probe doping practices in cycling, an independent commission to investigate the UCI and senior cycling management, independent doping controls, and "a cultural change at the UCI".

There has been some progress - a UCI commission, tasked with investigating its handling of the sport during the Armstrong era, and allegations of corruption within the organisation, has been disbanded, to be replaced with a truth and reconciliation committee.

'No satisfaction'

It is all a far cry from when the Australian entrepreneur started out in business, at his parents printing firm, and when he went on to launch his own print brokerage, outsourcing work to other companies.

Mr Fuller started his business career in printing and property development

"I then moved into property development, and as with printing it was very successful, but there was no satisfaction," he says.

In 2002 he was then asked by Skins, which had been founded six years earlier by Australian physiologist and ski enthusiast Brad Duffy, to come in as the firm's US distributor.

"I then had my Victor Kiam moment, and I bought the company," he says, referring to the US entrepreneur who bought Remington after his wife bought him an electric shaver.

At first he took a 49% holding, but by the end of 2004, after putting in much of his own money in a desire to take Skins "to the next level", he bought up the whole firm.

The firm launched in the UK in 2006, the US in 2007, and now - from initially selling one product, a pair of tights - sells more than 160 compression products, and has other regional offices in Australia, France, Germany and China.

It has distributors in another 14 countries.

Rugby League controversy

A major development, and one which explains his current stance, came at the end of 2007, when he was introduced to a London brand consulting firm called Eatbigfish.

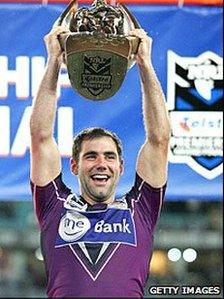

Melbourne Storm were stripped of two championships in Australia's National Rugby League

"We started this incredible brand values process, we wanted to define what we stood for, and looked for ways we could implement that in our culture as well as in our consumer facing, so that there was a degree of consistency.

"We defined the essence of our brand as standing for the true spirit of competition - not cheating, not taking drugs, not crossing the line."

Clauses to this effect were subsequently put into contracts that Skins signed with athletes and teams, and the firm vowed that if any of its sportspeople or teams were caught "systematically cheating" - on a regular and calculating basis - then the firm would "terminate the contract, and terminate it very loudly".

And that is what happened in 2010 when Australian Rugby League team the Melbourne Storm were caught systematically breaking the competition's salary cap.

Skins dropped the team, and Mr Fuller says he felt the fall-out both financially, and from fans.

"I got flak, I got death threats," he says. "The deal to us was worth millions, it was a good deal, but I said we could not be hypocritical, and we terminated the contract."

Short-term deals

As part of his anti-cheating stance and continued dissatisfaction with the UCI, Skins is suing the governing body for $2m, claiming its alleged inability to run a clean sport has caused the company to suffer.

This is the sum the firm feels it could legitimately claim - in terms of monies spent on things like sponsorship, advertising, research and development - if it was forced to withdraw from cycling.

Meanwhile, any new cycling sponsorship deals are now for one year, rather than the previous four, while Mr Fuller decides whether to continue his involvement with the sport.

"We are only signing short-term deals while we consider our position," he says.

"If things don't change, we will consider leaving cycling."