Budget 2013: Who has lost the most and the least?

- Published

- comments

The chancellor may find himself looking in the Budget for some extra sources of money for the government, to try to trim its borrowing.

If he does, it would make sense for him to look at who has taken the biggest hit so far.

It is possible to look at the impact of all the measures announced so far covering the period between the government coming to power in 2010 and the end of the tax year 2015-16, as the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) has done, external.

"The chancellor has said that those with the broadest shoulders should bear the biggest burden of any further consolidation," says Paul Johnson, director of the IFS.

Paul Johnson, director of the IFS, says the Budget may target those with the most wealth rather than the highest incomes.

"It is fair to say that up till now the highest-income people have, since January 2010, seen the biggest increases in tax, by some considerable distance actually."

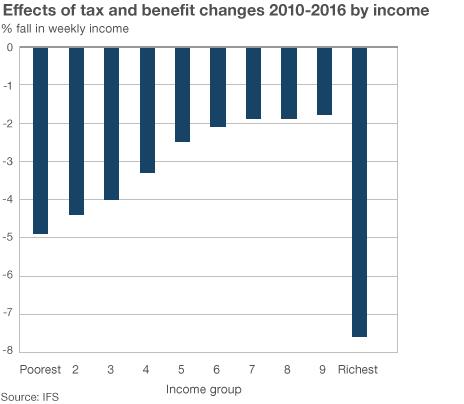

Indeed, IFS figures show that taking all the tax and benefit changes announced so far for 2010-16, the people with the top 10% of incomes will see those incomes drop by 7.6% on average.

Those on the highest incomes have been hit by measures such as the loss of the tax-free allowance for people earning above £100,000, loss of child benefit for higher earners and restrictions on how much they can contribute tax-free to their pensions.

In percentage terms they have lost considerably more than the next worst-hit group, which is the poorest 10%, who are expected to see their incomes drop by 4.9%.

So on this analysis, there is little sign of the so-called squeezed middle. Those with incomes above the bottom 10% and below the top 10% have benefited from the increases in the amount they can earn before they have to pay any income tax, even if they have suffered from their wages failing to keep up with rising prices, which is not reflected in these figures.

"If you look at the groups who have been less affected, it is actually those in the upper-middle bits of the distribution, perhaps basic rate taxpayers, where you have a couple who are both earning, particularly those without children," Mr Johnson says.

"They've not been very much affected at all by the tax increases we've seen so far, so he [the chancellor] might decide to go for that group, though electorally that would be difficult."

Households on the lowest incomes have been disproportionally hit by benefits to people of working age and tax credits being raised by less than the rate of inflation.

Of course, income level is not the only way to consider the effects of tax and benefit changes - the IFS also considered types of households.

Clearly it would be tempting to try to get couples with two earners and no children to take on more of the burden, although technically it might be difficult to do so.

In this analysis, pensioners are among the least hit groups, with a single pensioner's income falling an average 2% and a pensioner couple down 2.3%.

There have been calls for wealthy pensioners to be taxed more, although that would also be politically difficult.

Last year, a report from the Free Enterprise Group of Conservative MPs called for ministers to be "brave enough" to tell the wealthiest pensioners that their benefits would be cut.

They suggested doing things such as taxing winter fuel allowance or even removing it from pensioners who are higher-rate taxpayers.

The chancellor may also decide to ignore income and go for a different group instead.

"He may decide to look at those who have got high levels of wealth, which is actually a bit of a different group to those who have high levels of income, so a mansion tax, for example, for those who have very expensive houses, or looking through things like inheritance tax or capital gains tax," Mr Johnson says.

The idea of a tax on properties worth more than £2m came from the Liberal Democrats, although it is not part of the coalition agreement, but it has now been adopted by Labour.

A vote on it was defeated in the Commons last week.

So, the groups hardest hit by changes in taxes and benefits are those with the highest 10% of incomes followed by the lowest 10%.

The hardest hit types of households are those on working-age benefits, with four of the top five categories being households with nobody working.

Pensioners and working households without children have been hit relatively less hard.