Budget 2013: What might be in it?

- Published

Chancellor George Osborne will deliver the 2013 Budget on Wednesday, against the backdrop of dissent from his own backbenches and the longest period of economic stagnation in the last century.

He is under pressure to pull back on his plans for cuts which will reduce borrowing, and to come up with measures that will create jobs.

But there is no indication from the government that it will change economic course, and there is little money for headline-grabbing measures.

Mr Osborne did, however, tell the BBC on Sunday that he was determined to do the right thing by the economy. His Budget would help people who "want to work hard and get on, own their own home and save for their retirement".

So what can we expect from the chancellor's fourth Budget?

The deficit

The deficit is the amount that the government has to borrow every year to cover the gap between the amount it spends and the amount it receives in tax.

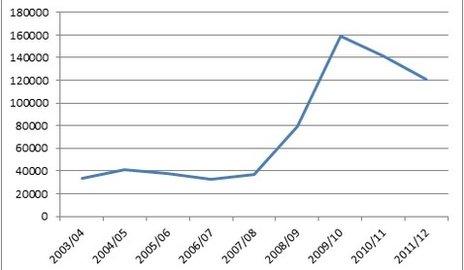

The government proudly states that, from 2009-10 to 2011-12, it has succeeded in cutting borrowing by nearly 25%.

But while overall it has come down in the last couple of years, borrowing is still considerably higher than before the start of the recession in 2008.

Amount borrowed each year in millions of pounds (Graph shows £0 to £180bn)

On Budget day, the independent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) will provide fresh forecasts as to how much the government has borrowed in 2012-13 and how much it expects to borrow in the years to come.

Many forecasters believe the downward trend will be reversed and borrowing will go up, not down, for the first time since this government came to power.

The chancellor only narrowly avoided this embarrassment in last year's Autumn Statement by the inclusion of the sale of 4G mobile licence receipts in the figures.

However, given that the economy has performed even more poorly than he had expected and he received less 4G money than he hoped, the chancellor may be forced to announce borrowing is rising, which risks damaging the government's political credibility.

Growth

In previous Budgets and Autumn Statements, the chancellor was forced to lengthen his plans to dramatically cut the size of the overall deficit and eliminate it on its chosen measure, known as the structural deficit.

He now believes this will take until 2017-2018, rather than in 2014-15 as he had initially expected.

This is partly as a result of weak growth which has meant the amount of tax the chancellor has received has been much lower than he and the OBR predicted. Indeed, since the first full quarter of George Osborne's time as chancellor, the economy has grown by only 0.7%.

Some 56 months after the start of the first recession in 2008, the UK economy is now more than 3% smaller.

This is much worse than the other most severe recessions in modern times: In the 1970s and 80s, and during the 1930s, the economy had returned to its pre-recession size after 47-48 months.

As part of its forecast, the OBR will say whether or not it thinks the UK will slip back into recession this year for the third time.

If it reduces the UK's growth forecast, the chancellor will find it even more difficult to balance the government's books and may have to seek further cuts or tax rises.

All change at the Bank?

There has been a great deal of speculation as to what changes could be made to the Bank of England to help the economy get back to sustained growth.

In July, the current governor, Sir Mervyn King, will make way for Canadian Mark Carney.

He and others have expressed interest in expanding the Bank's role in some way, potentially targeting growth or unemployment alongside its current target of ensuring inflation is around 2%.

One of the chancellor's formal responsibilities in the Budget is to reconfirm the Bank's remit. It is possible he might change it on Wednesday or open the matter to consultation before Mr Carney assumes the role of governor.

With little money to spend on the fiscal side of the Budget, any changes to monetary policy and the Bank could be the most significant of Mr Osborne's announcements.

He may also expand or adjust the Bank of England's Funding for Lending Scheme which, though designed to increase lending to small business and individuals, has disappointed some.

More spending cuts

George Osborne told a cabinet meeting on Monday that he will announce that government departments will have to cut their spending by a further 2% over the next two years, raising around £2.5bn of extra money earmarked for infrastructure projects.

The cuts come on top of the planned 3% extra reduction in spending for the next two years announced in last year's Autumn Statement, with the money raised again going to infrastructure.

Infrastructure

Business groups want investment in projects like house building that can start immediately

At the heart of the political debate will be a central question: Should the chancellor abandon his plans to keep cutting borrowing over the next few years in order to spend more on infrastructure and capital projects to create jobs, restore confidence and foster growth?

Deputy PM Nick Clegg recently provoked controversy when he indicated that the government had moved too quickly to cut capital spending in the June 2010 emergency Budget.

The government did partially reverse some of those cuts and the chancellor is known to favour diverting government resources to capital and infrastructure spending, as in the 2011 National Infrastructure Plan, external.

And in part, the chancellor's decision to use £2.5bn of extra savings from departmental spending on infrastructure projects suggests he agrees it is a good way to boost the economy.

The government should provide some updates on the projects it has already announced and will probably announce a few more.

After the Heseltine Review into delivering greater regional growth, the chancellor may spell out the government's response, with changes to the way skills and economic development funding is spent in England.

Pensions and care

The chancellor disclosed two new measures on Sunday, telling the BBC that the government would bring forward its changes to pensions and social care funding.

The proposed flat-tier pension, worth about £144 a week, would now start in 2016, a year earlier than previously planned.

Mr Osborne told BBC One's Andrew Marr Show that the "generous" flat-tier pension would be "a huge boost for people who want to save for their retirement".

He also said that a cap on the amount the elderly pay for social care in England, originally planned to be set at £75,000 and introduced in 2017, will now also be introduced in 2016 at a level of £72,000.

Tax changes

Several tax changes are already pencilled in for 1 April including the reduction of the top rate of tax, to 45p, and an increase in the personal tax allowance, which will rise from £8,105 to £9,400.

It seems probable that the chancellor will indicate a further increase of the allowance to reach the coalition agreement's stated £10,000 ambition. This is the amount that you can earn before you start paying tax.

He may also signal a further reduction in the rate of corporation tax to 20p. He already plans to reduce the rate to 21p by June 2014, down from a 28p rate when he took office.

In the wake of recent tax avoidance scandals, the chancellor might provide new details as to how he intends to make companies pay more tax.

Over the weekend, the government said that it would close a loophole that allows firms to avoid paying £100m a year in National Insurance.

Alcohol and fuel duty

The next rise in fuel duty may be delayed - a common occurrence

The Budget could prove to be bad news for drinkers, but relatively good news for drivers.

After the government's perceived U-turn on minimum alcohol pricing, it is possible that the chancellor will attempt to appease health campaigners with some rises in alcohol taxes above the automatic increases - of 2% above inflation - which will automatically take effect in April.

Extra revenue raised here might fill the gap left by a potential suspension of a fuel duty increase planned for the autumn, which will please motorists.