An 'optimal' Budget?

- Published

- comments

George Osborne has not had much space to move

They say economics is all about "constrained optimisation" - you try to get the best outcome, subject to numerical constraints. It's the same for chancellors.

In the overall scheme of things, he didn't do much. But if ever there was a chancellor constrained by economic and political circumstances it is George Osborne. And they just got a bit worse.

Growth is down this year and next - with the fall in the forecast for 2013, from 1.2% to 0.6%, quite a lot bigger than most had predicted. The Office for Budget Responsibility, external (OBR) is now on the gloomier side of the spectrum of independent forecasters. Though, historically, it has not stayed that way for long.

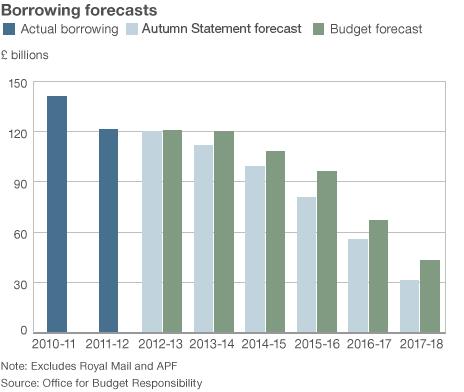

Borrowing is up over the medium term, as everyone predicted - meaning the UK public net debt in 2015-16 will be £60bn higher than forecast in December.

The structural hole that the chancellor set himself to fill has also risen - the OBR thinks his target measure of the deficit in 2013-14 will be 2.8% of GDP, not 2.2%, as it thought in December - or 0.7%, as it forecast in June 2010.

When he wrote that first Budget, Mr Osborne thought he would have eliminated that measure of the deficit entirely by 2014-15. Now it will take him until 2016-17, and the margin for even that success is just 0.1% of GDP.

Even that tiny margin for error is large compared to the amount that the government can claim the deficit has fallen in the past year. There are numerous measures of borrowing listed on page 160 of the OBR's Economic and Fiscal Outlook, external, depending on how many special factors you strip out of the total.

If you get rid of all of those one-offs - including a new one, related to transfers due to the Special Liquidity Scheme (SLS), external for banks - then borrowing has risen very slightly between 2011-2 and 2012-13, from £121bn to £123.2bn.

However, though the OBR has bothered to provide us with this stripped down figure on table 4.36 of its report, it seems comfortable to use the borrowing numbers highlighted, unsurprisingly, by the Treasury. These include the SLS transfers (but not other special factors) and show borrowing falling by £0.1bn, from £121bn to £120.9bn.

For reference, that £0.1bn difference compares with an average forecasting error, for borrowing numbers one year out, of £12-15bn.

'Wide margin'

The big picture, underscored by the OBR itself, is that the deficit will be more or less the same in 2011-12, 2012-13 and 2013-14: around £120bn.

Of course, there's an enormous amount of politics in the details. But the economic story, as the OBR director, Robert Chote said himself, is that the effort to cut the overall deficit has stalled. It has been put on hold for three years by the weak economy.

As you know, city experts were predicting borrowing would rise a lot more than this. How did the chancellor avoid this fate?

The OBR gives us a large part of the answer in page 128 of its report, which explains how the expected under-spend by government departments in this fiscal year has risen, in just a few months, from an already high £7.5bn to an astonishing £10.9bn.

As the OBR itself says, it is "very rare for the government to under-spend the departmental plans it has set out less than a year ago by such a wide margin".

Paragraph 4.118 explains the elaborate efforts involved in coming up with such a large number, which include delaying payments to bodies such as the World Bank, by a matter of weeks, so as to get them into the 2013-14 tax year instead of 2012-13.

It's not the first time that a Treasury had used these tactics. But you have to wonder whether Mr Osborne will continue to talk quite so much about the fiscal fiddles that went on in the Gordon Brown era.

The OBR itself "sees some risk" that some of the payments now tabled for 2013-14 will actually be made in 2012-13, as previously planned.

If that happened, we would find, next time the chancellor stands up, that spending in 2012-13 has gone up again, and spending in 2013-14 has gone down.

Call me crazy, but I don't think that is a risk that will unduly concern Mr Osborne. It could even make it easier for him to say borrowing has fallen next year as well. Imagine that.

So much for the fiddly details. The big picture is that the chancellor has done a little more than expected, given the great economic and political constraints that he is labouring under.

But we can say that Whitehall has bent itself to the chancellor's will, even if the economy has not.