Will Cyprus go the South American way?

- Published

Cyprus's banks aren't working

As the financial crisis in Cyprus has unfolded, every new development has been greeted by a chorus of analysts describing it as "unprecedented".

Freezing all bank accounts, trying to make account holders pay for the clean-up, talk of nationalising the country's pension funds - all these things are pretty much unheard of in a modern European state.

But there is a part of the world where such events are all too familiar. Over the past few decades, South Americans have experienced all these trials and tribulations.

And while some countries in the region have emerged stronger, others are still stuck in the same cycle of economic turmoil.

Brazil's 'confiscation'

For Brazilians, the events in Cyprus over the past few days have stirred up memories of a time they would rather forget.

In newspaper articles about the Mediterranean island's troubled banks, one expression has repeatedly cropped up: "o confisco".

That term - in plain English, "the confiscation" - will forever be associated in Brazilian minds with 16 March 1990, the day after the inauguration of the country's first democratically elected president since the end of military rule.

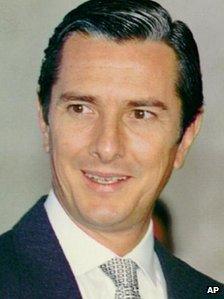

President Collor angered Brazilians without solving the country's problems

The new leader, Fernando Collor de Mello, had chosen as his finance minister the unrelated Zelia Cardoso de Mello, the first woman to occupy the post.

In her first act, Zelia, as she was known, went on national television to tell the country that all bank accounts were being frozen and that no-one could access more than 50,000 new cruzados in the currency of the time (a sum then worth about $1,250).

The move was part of a package of measures known as the Collor Plan, aimed at combating the country's chronic high inflation.

The rest of account holders' money was untouchable for the next 18 months, by which time it was worth a great deal less, thanks to the very inflation that the move had been designed to reduce.

The plan did have some temporary success. Annual inflation declined from nearly 3,000% in 1990 to under 500% in 1991, but then it shot up again in subsequent years. It finally took another finance minister, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, to tame hyperinflation with his Real Plan.

His success was rewarded when he won Brazil's 1994 presidential election, followed by a second term in office four years later.

Since then, the confiscation has gone down in history as a measure that inflicted pointless pain on the population.

From a European point of view, the most surprising aspect is that Brazilians largely put up with it. There was no immediate public outcry, unlike in Cyprus now.

Street protests against the Collor administration did eventually happen, but not until 1992, after the president became embroiled in an influence-peddling scandal that led to his resignation.

Argentina's pension grab

Since attempts to impose a confiscation in Cyprus have run into so much resistance, other options are now being explored.

The EU bailout deal requires the government in Nicosia to come up with 5.8bn euros ($7.5bn; £4.9bn) as its share of the 10bn euro plan. If bank customers decline to pay, someone else must do so.

The latest idea is to take over the pension funds of local corporations, which could yield 2bn to 3bn euros.

Argentina's president is running out of economic options

Again, this is a largely untested idea in Europe, but there is a major precedent in South America.

Argentina has been unable to gain access to world credit markets since its economic meltdown and $102bn debt default in 2001-02.

The country has already struck deals with the majority of its creditors. Yet before it can raise new loans, it needs to settle its outstanding debts, most of which are held by the informal Paris Club group of lenders, which represents 19 of the world's largest economies.

In the meantime, President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner has had to seek creative solutions to her cash-strapped nation's problems.

In November 2008, she persuaded the Argentine Congress to pass a bill nationalising private pension schemes worth at least $23bn - a much larger sum than the one now at stake in Cyprus.

This and other measures have reinforced the image of Argentina as a financial pariah.

It remains a member of the G20 group of nations, even though its financial crisis caused it to drop out of the world's top 20 biggest economies. But it may yet be expelled from the International Monetary Fund in a row about the unreliability of its official inflation figures.

Argentina may have the clout to go its own way, but little Cyprus is far more dependent on international goodwill to stay afloat.

Currency on lockdown

Of course, the problems in Cyprus are part of a much larger crisis affecting the entire eurozone, caused by a "one-size-fits-all" currency regime that gives member nations no flexibility.

Argentina, too, has suffered in the same way.

Cyprus, which adopted the euro in 2008, has its monetary policy decided by the European Central Bank in Frankfurt.

In contrast, Argentina has always kept its own currency, the peso. But under the Law of Convertibility, passed in 1991 and not abandoned until January 2002, its value was fixed at parity with the US dollar.

That policy was the brainchild of President Carlos Menem's finance minister at the time, Domingo Cavallo, as a way of restoring the currency's credibility after years of rampant inflation.

Initially, it worked well. But later, efforts to defend the currency peg led to unpopular spending cuts, since monetary policy was in effect being decided in Washington, not Buenos Aires.

Argentina had let its public debt get out of control, as Cyprus has now - although Cyprus's position is worse, with public debt now at 87% of GDP, as opposed to 62% of GDP in Argentina in 2001.

And on top of that, Cyprus has a banking sector on the brink of collapse.

In all, Cyprus has much to learn from Latin America. However, it should take the region's examples not as a path to follow, but as an awful warning.