Cyprus's future: Is euro membership viable?

- Published

Is it game over for Cyprus as the financial services sector crumbles?

What is the future for the Cypriot economy following a 10bn-euro bailout deal with the European Union and the International Monetary Fund?

To ask about a country's long-term prospects in the middle of a financial crisis is something of a fool's errand.

How the future pans out for Cyprus will depend crucially on what happens over the coming days, weeks and months.

Will Cyprus be able to lift restrictions on bank accounts quickly? Will the banking system recover? Will the offshore banking business evaporate?

While we can only speculate at the answers to these questions, two conclusions stand out:

The short-term is looking very bleak and could involve a 20% shrinkage in gross domestic product (GDP) by some estimates, external

The longer-term is, at best, uncertain and largely outside the country's control

Bank malfunction

The immediate problem facing Cyprus is how to restore confidence in its banking system.

The job of its banks is to keep the flow of money to the economy going. Disrupting that flow is akin to disrupting the flow of blood to the brain.

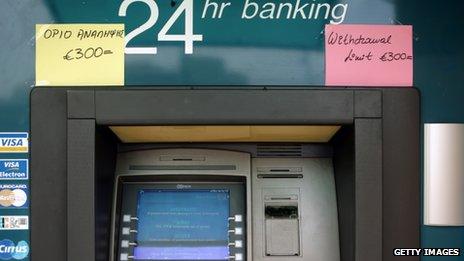

Since the banks reopened - after closing for two weeks - there remain limits on how much access Cypriot people and companies have to their money.

The continuing malfunction of the banks has two nasty consequences.

First of all, capital controls - and a suspension of lending - prevent the normal functioning of the economy by starving businesses and households of the means of payment.

There are potentially permanent consequences if these measures stay in place for too long.

A British woman tells the BBC's Tim Willcox she could lose 40% of her savings after retiring in Cyprus

For example, Cypriot businesses face limits on their ability to pay suppliers, and may have to lay off staff and sell off valuable assets in order to survive.

Much of the cash they held at the two biggest banks - the defunct Laiki and the restructured Bank of Cyprus - has now been lost forever.

As the weeks pass with restrictions still in place, the incentive will strengthen for Cypriots to hoard assets - such as euro banknotes, jewellery, even yachts - that can then be moved offshore, further disrupting economic activity.

What the authorities hope is that, once hefty losses have been calculated and imposed on the trapped depositors at the two banks, the European Central Bank (ECB) will deem the Cypriot banks to be sufficiently healthy again.

Then the controls can be quickly lifted because the ECB should be willing to lend the banks whatever cash they need to meet depositor withdrawals - as happened with Greece's bank run last summer. The ECB may also need to airlift a few million extra banknotes to Nicosia, external.

Feeling deflated

The second consequence of the country's continuing economic crisis is that, even if confidence can be rapidly restored and restrictions are lifted, the banks will remain over-bloated and will still be unable to perform their role as lenders for many years.

The banking system had grown to eight times the size of the Cypriot economy's annual economic output, external - or GDP - although the restructuring of the two biggest lenders should significantly shrink that number.

Much of that bulk is due to the country's role as an offshore tax haven - with Russian money being recycled into ill-judged loans to Greece.

But Cyprus is now also suffering from the deflation of a property bubble.

Property prices rose 50% between 2006 and their peak in 2009 - as the banks lent readily to home buyers, landlords and property developers - and have since fallen steadily, external.

This has had a predictably negative impact, external on activity and employment in the construction sector.

It has also affected confidence among mortgage borrowers, the ability of companies to borrow against property to finance investment, and the ability of property developers and speculators to repay their existing loans.

Construction activity has halved, from 12.8% of economy in 2007, to 6.1% last year. However, other property business - including landlords' rents and the activity of estate agents - represents a surprisingly elevated 11.6% of the economy.

Taxing matter

A longer-term concern is whether Cyprus' financial services sector - which contributes 9% of the economy - has a future.

Germany suggested that a condition of the island's bailout was that its many offshore depositors should also bear the brunt of the losses.

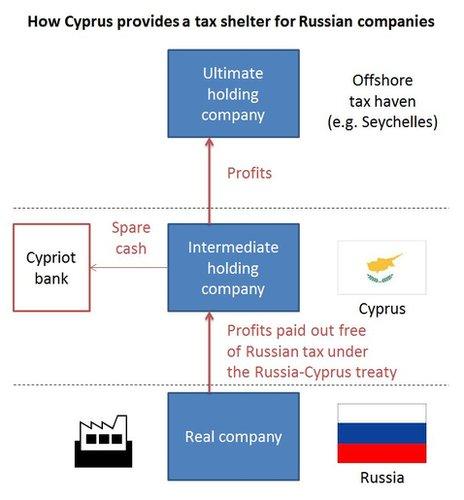

The country's role as an offshore tax haven dates back to 1982 when the island signed a tax treaty with the USSR - which has allowed Russian businessmen to completely avoid paying tax on the profits their businesses make in their home country.

But Russia has threatened to cancel its treaty, external.

Its businessmen have undoubtedly lost a chunk of money in Cyprus.

But, as the country serves a useful purpose, it is unclear whether that means they will stop doing business there.

Using Cyprus as a tax haven does not necessarily require them to hold a lot of money in the country.

It merely requires them to wash their Russian profits through a Cypriot holding company which, in turn, is typically owned by another company in a third country which - unlike Cyprus - offers a zero corporate tax rate.

Whether the offshore business has a future ultimately depends on political decisions made in Moscow, Brussels, Berlin and Frankfurt, over which Cyprus can only hope to have some influence.