Margaret Thatcher: How her changes affected your finances

- Published

During her years as prime minister, Margaret Thatcher revolutionised the economic fortunes of every person in the UK.

Giving people the right to buy their council houses and shares in previously nationalised firms such as British Telecom and British Gas were among the initiatives that won her much support.

But some believe that other changes, such as those that made mortgages and credit much easier to get, sowed the seeds of future crises that still affect many to this day.

Here, BBC reporters look at some of the changes that, for better or worse, have changed our finances forever.

Right to buy

The King family in Milton Keynes receive the deeds to their council house in 1979

By Brian Milligan, personal finance reporter, BBC News.

The Right to Buy Scheme for council houses was one of Margaret Thatcher's most popular policies.

It was enshrined in the Housing Act of 1980, making it one of her first major pieces of legislation after she came to office in 1979.

The number of people who bought their council house from their local authorities rose to 200,000 by 1982, and again peaked at 180,000 in 1989, her last full year as prime minister.

Since the Housing Act came into force, it is estimated that some two million homes have been sold to former council tenants.

The sale price was based on market valuation, but included substantial discounts, depending on how long a tenant had been living there.

When Labour came to power in 1997, it reduced the value of such discounts in areas where councils were running short of housing stock.

Critics said the policy resulted in speculators buying up valuable housing stock too cheaply.

The Right to Buy Scheme was extended in the March 2013 Budget, as the government vowed to increase sales once again.

Credit and savings: Seeds of future crises

Holiday money in the 1970s was strictly controlled

By Simon Gompertz, personal finance correspondent, BBC News

Before Mrs Thatcher arrived at No 10, British passports contained a special page to record the amount of cash travellers took out of the country.

The page was one of the first things to be scrapped by the new government, as the Tories moved to abolish exchange controls.

The Chancellor, Geoffrey Howe, raised travel allowances to £1,000 per trip and permitted overseas property purchases of up to £100,000.

On the tax front, the basic rate was cut by 3p to 30p in the pound, while the highest rate came down from 83p to 60p.

But Thatcher's chancellors not only cut income tax, but also changed the way we pay tax.

To fund lower taxes on incomes, up went tax on most things shoppers bought. VAT, or value added tax, jumped from 8% to 15%.

Within a few years, the basic rate of tax had fallen to 25%, while the higher rate had been slashed to 40%.

Credit unleashed

With money from tax cuts in their pockets, shoppers began to rediscover the "feelgood factor". They were encouraged further as credit was unleashed.

Restrictions on hire purchase offers were relaxed, stores offered credit, credit cards boomed. Consumer borrowing tripled during the 1980s.

And, of course, mortgages were easier to get. The old rule of thumb that you only borrow two-and-a-half times salary was thrown out of the window.

Building societies were allowed to lend more and foreign banks set up in the UK to compete.

The Bank of England did not control the expansion of credit and there are those who see the roots of the current financial crisis in the credit boom of the Thatcher years.

Private pensions

Mrs Thatcher wanted self-reliance, not reliance on the state. That was the thinking behind the launch of personal pensions in 1988.

The new plans provided a route to save for those who did not have a company scheme. But, sadly, they backfired.

The promotions and publicity got out of hand. Advisers went to town, encouraging savers to switch out of solid traditional schemes into riskier personal pensions.

Compensating the victims cost the pensions industry £11bn.

More successful were personal equity plans or Peps, designed to encourage savers to salt away up to £6,000 a year in shares, in exchange for a tax break.

To complement Peps, John Major, the last chancellor of the Thatcher era, introduced a tax-free vehicle for cash savings, the Tessa.

The idea caught on. Peps and Tessas later morphed into individual savings accounts, or Isas, in which Britons have £390bn salted away.

Union rights

By John Moylan, employment correspondent, BBC News

Few senior trade union figures have commented on the death of Baroness Thatcher. That silence speaks volumes for the lasting legacy that her reforms had on the power of the movement.

She was ushered to power in the wake of the Winter of Discontent when a wave of strikes paralysed many parts of the economy. Rubbish was piled high in the streets as collections stopped. And famously, gravediggers went on strike.

The Conservative government set about a series of changes to employment and trade union laws, which ended mass picketing, secondary action and the closed shop, where staff had to join a union to get a job.

Secret ballots were introduced, as were restrictions on holding legitimate disputes that still rankle with the unions to this day.

In 1979 there were more than 29 million working days lost to strike action. These days, that number is typically well below one million.

The miners' strike of 1984-85 came to symbolise the government's battle with the unions. The year-long dispute over pit closures led to repeated scenes of violence as striking miners clashed with police.

In the end the miners went back to work. The balance of power in industrial relations had shifted forever.

Unions insist that the collapse in traditional manufacturing industries during the 1980s did as much to diminish their power. Membership fell from over 12 million in 1980 - today there are fewer than 6 million members of Trades Union Congress-affiliated unions.

One of the first actions of the Labour government in 1997 was to repeal the ban on unions at GCHQ - the Government Communications Headquarters - imposed under the Tories. But under New Labour, the main planks of the reforms of the Thatcher years remained unchanged.

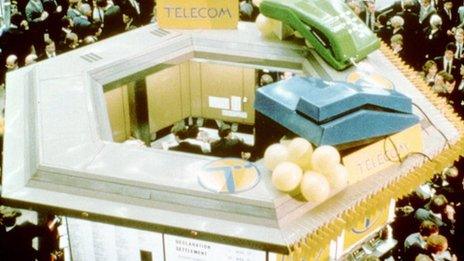

A share-owning revolution

BT privatisation day at the London Stock Exchange was a big event

By Kevin Peachey, personal finance reporter, BBC News

A policy of privatising the UK's large utilities revolutionised share ownership in the UK, and as such it was widely popular with many, though the initiatives also had their critics.

The recession of the early 1980s created the environment that allowed the Conservatives to drive forward the idea of moving nationalised industries into private ownership.

By the end of its first term, it had already privatised British Aerospace and Cable & Wireless. British Telecom, British Airways, British Steel, as well as water and electricity firms were among those privatised later.

This led to a new wave of first-time shareholders in the UK.

The advert for the sale of British Gas shares became one of the most celebrated campaigns

One of the first privatisations and arguably the most memorable - through a celebrated advertising campaign - was the sell-off of shares in British Gas in 1986.

The promotional campaign featured TV adverts in which characters urged each other to "tell Sid" about the chance to buy shares at "affordable" prices.

Anyone who has held on to these shares will now have a portfolio that includes a stake in Centrica, BG Group and National Grid.

Privatisation was key to the Thatcher government's economic policy. As a result, it hoped that the large subsidies granted to industry over the decades would be eventually phased out, allowing for further tax cuts and controlling borrowing.

It also encouraged the idea of members of the public owning shares in big former monopolies.

Yet, figures from the Office for National Statistics show that the percentage of the UK stock market owned by UK individuals was higher in the 1960s and 1970s in terms of value, than the 1980s.

In 1981, 28% was owned by UK individuals. This had fallen to 20% by the end of the Thatcher term in 1990. Yet it fell to just over 11% by the end of 2010.

The Big Bang

Traders on the London Stock Exchange were a close-knit bunch

By Rebecca Marston, business reporter, BBC News

The impact of one of Margaret Thatcher's deregulation drives was the drastic reorganisation of the way shares were traded in the UK.

The so-called "Big Bang", introduced on 27 October 1986, made it far simpler to trade shares on the London Stock Exchange.

The most visible reform was that traders no longer stalked the floor of the Exchange, animatedly dealing with each other face-to-face.

Big Bang moved them at a stroke from that to screen-based and telephone trading.

It also broke up what many saw as a gentlemen's club, ruled by restrictive practices. (It is worth noting that there were almost no women and the gentlemen described came from a far wider class base than the phrase suggests.)

Before Big Bang, share dealing was done through a stockbroker, who advised clients on dealings. Transactions were carried out by jobbers, who made markets in shares - physically seeking out others with whom to trade on the Stock Exchange floor.

Price competition was not allowed, fixed commissions were the norm.

At best it was a self-regulating club, where bounders could easily be spotted, but at its worst this club fostered insider dealing and share price ramping.

Big Bang saw many of the City's historic names disappear in a frenzy of takeovers as banks jostled to buy jobbers and stockbrokers in order to become one-stop shops.

This, in turn, unleashed a succession of takeovers by even bigger organisations, the giant American finance houses.

Big Bang helped facilitate privatisation, demystifying the share-buying process that many ordinary people had found a stumbling block, thus allowing people to simply walk into their banks and order a parcel of shares.

But while it made dealing and investing easier, it also paved the way for the creation of giant financial institutions, whose size has meant their health is critical to the wellbeing of the general economy.