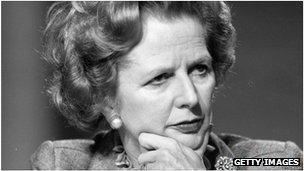

Margaret Thatcher: The economy now and then

- Published

She changed the country, yes. But did she make it better? That's the question lurking behind the deluge of commentary following Baroness Thatcher's death - and in the fascinating parliamentary debate in her honour.

For me, the lesson of all that talk is that it is a very difficult question to answer without caveats and qualifications, and not just for the usual reason, that her policies "divided the nation". It's also because the market economy she helped to bring to the UK is itself such a many-sided thing.

The market can be miraculous - the greatest vehicle for wealth creation the world has ever known. But it can also wreak havoc - economically and socially. Margaret Thatcher gave Britain its first big lesson in both.

You might say that policymakers on both sides of the political divide have been looking for a middle way between those two things ever since, a way to get the miracle without the misery.

The global financial crisis taught us we haven't found it yet. But, you can bet that politicians will keep looking for the right balance between government and market: how to provide a safety net for the unemployed without discouraging work, for example, promote financial markets without also promoting unsustainable debts, or balance the government's books without tanking the economy.

Experiment

How do today's versions of those policies compare with hers?

Like Thatcher, Iain Duncan Smith thinks the welfare system he inherited saps individual initiative and traps people in long-term dependency, at an unacceptable cost to the state. Thatcher had one answer to that. Universal Credit is Iain Duncan Smith's. We'll start to see this year how his experiment works out.

The removal of exchange controls and easing of credit restrictions were Thatcher's first big moves to free up the financial system. (Hard to believe, now, that in 1979 we were still only allowed to spend £50 a year abroad.) The "Big Bang" reform of the City in 1986 was another important step along the road, though the bang is probably remembered as bigger, now, than it was at the time.

Many would argue that Gordon Brown's "light-touch regulation" and general deregulation of banking, in the UK and around the world, did more to "unleash" the City than anything Margaret Thatcher did, and more to pave the way to the financial crisis.

Higher international capital and liquidity requirements, plus the government's decision to put the Bank of England back in charge of regulating banks, are this government's attempt to have the benefits of free financial markets without the accompanying disasters. Years from now, we'll be drawing our own conclusions about whether they got the balance right.

And macroeconomic policy? What about that?

Monetarism

Thatcher's macroeconomic policy was front and centre of the debate when she was in office - at least in the first few years. Oddly enough, it hasn't featured very prominently in the many articles on her legacy that economists have written this week. That might be because most of what was new in her monetary and fiscal policies didn't really work.

The experiment in "monetarism" - using the control of the money supply to control inflation - was quite quickly abandoned. Purists would say it was never really tried. And only on the back of an unsustainable economic boom in the late 1980s did she manage to make serious progress in shrinking the relative size of the state. Public spending was around 45% of national income when she took office, and it was 45% again in 1985, having risen as high as 48% in 1982-3. Spending only fell below 40% at the end of the decade, and then only briefly.

In real terms, you might be surprised to hear that there were only two years in Thatcher's time when spending fell at all. According to the IFS, real spending grew by 1.3% a year between 1979 and 1990.

In that sense, George Osborne is planning to be much tighter than she ever was. His plans allow total spending to grow by just 0.3% a year in the five years from 2009-10. And remember, that total includes rising debt interest and social security payments. He's squeezing most government departments far more than Thatcher did.

His austerity plans are almost as controversial as Thatcher's were in 1981. But it's worth noting that the deficit she inherited was a lot smaller. In 1979, the gap between public spending and tax revenues in 1979 was 4.1% of GDP.

I'm tempted to say, a "mere" 4.1%. For all his toughness, Mr Osborne has had to resign himself to borrowing more than that amount for the entire Parliament. The deficit is not even forecast to get below 5% of GDP until 2016-17 - which is one reason why at least one ratings agency has decided that Britain's sovereign debt is no longer triple A. The deficit was 11% of national income when he took office, more than double what it was in 1979.

Economic hole

You could say the stakes in today's argument over austerity are even higher than they were in the early 1980s. Not only is borrowing higher, but the hole in the economy is also worse than it was then.

Can Margaret Thatcher take any credit for the resilience of employment since 2008?

The recession of Thatcher's first term was the worst since World War II, but national output still managed to grow by 5% in the five years after 1979. In the five years since 2007, Britain's national income hasn't grown at all - in fact our economy is 2% smaller than it was at the start of the downturn. And growth in the ten years after 2007 is now forecast to be just 0. 8% a year - one-third of the average growth rate under Thatcher.

But, bad though it is, I don't think the average person would say that Britain's economic situation was as desperate today as it was in the late 1970s.

There are lots of reasons why that might be the case - not least, the fact that our living standards are higher now than they were then. We are a much richer nation. But the lower level of inflation and unemployment surely also makes a big difference.

Even though inflation has been well above target for several years, it has never got close to the 22% it reached in 1980. And even though joblessness has risen to 2.5 million since 2007, it is not as high as it was in the 1980s - despite a deeper recession.

As a share of the labour force, unemployment peaked at 12% in 1984, and was hovering around 10% for more than half of Thatcher's time in office. It has risen about 2 percentage points since 2007, but it has not gone much above 8%.

Can Margaret Thatcher take any credit for the resilience of employment since 2008? Well, many economists would say the supply side reforms she introduced (including toughening up the welfare system and reining in the unions) helped make the labour market more flexible - so when recession struck in 2007, wages took the strain rather than jobs.

Though monetarism was a flop, her fans would also say she paved the way for a less political approach to monetary policy, including an independent Bank of England.

Needless to say, her critics would give her a lot less credit. But the human cost of bringing down inflation in the 1980s surely did leave its mark on policymakers - even those who were very young at the time. That is one part of Thatcher's legacy where policymakers across the political spectrum can unite in saying "never again".