Should bishops run the banks?

- Published

- comments

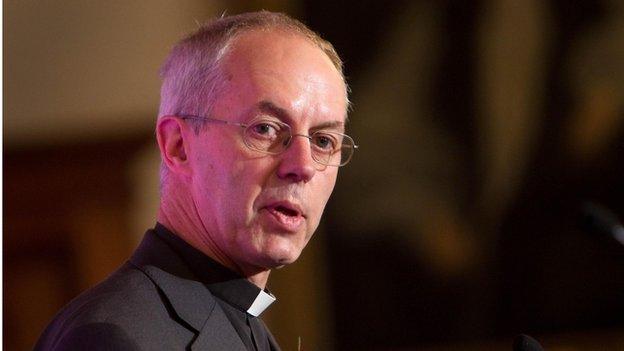

Justin Welby's most eye-catching reform would be for a big bank to be strengthened and then broken up into regional banks.

The newish Archbishop of Canterbury has strayed into unusual territory for such a senior prelate, which is to make some proposals to mend the banking system and British economy.

Serious reform is necessary, he said, because we are in "a serious depression".

That is true in the technical sense (as Stephanie and I have bored you to tears about) that national output is still 3% below where it was at the peak of March 2008.

But Archbishop Welby was making a related though different qualitative point - to the effect that the UK is in one helluva mess (to use an ecclesiastical term).

His most eye-catching reform would be for a big bank - presumably Lloyds or Royal Bank of Scotland - to be strengthened by having much more capital pumped into it and then broken up into a number of smaller regional banks.

This would be pretty expensive for taxpayers, both because of the capital we would need to inject into the bank, and because breaking it up would involve pretty horrendous IT challenges.

Archbishop Welby: ''What we are in at the moment is not a recession, but essentially some kind of depression''

That said, there might actually be benefits for taxpayers and others shareholders: as Andy Haldane of the Bank of England has argued, once banks get to a certain size, diminishing returns may set in.

To elucidate, some banks have become too big and complicated to manage safely - which would perhaps be the lesson of the 2007-08 debacles at UBS, RBS and Citigroup, inter alia.

But making investors or taxpayers wealthier is not the primary motive of the head of the Church of England.

His view is that better banking from an economic and moral perspective requires bankers to have a closer and more personal relationship with customers - and this could be achieved both by forcibly turning an RBS or Lloyds into a set of German-style regional banks, and by regulatory reform that would make it easier for local banks to flourish.

He also made the point, which none of the MPs or Lords present challenged, that banks have an obligation to endeavour to be "good" institutions: all companies are social constructs, so the normal rules of morality ought to apply to them; and that may be particularly true of banks, since there is an implicit contract provided by citizens or taxpayers that we won't allow banks to fail (that contract became explicit in the banking crisis).

Ethical argument

But why should anyone care what this man of the cloth says about the men - and occasionally women - who provide vital credit to businesses and households?

Well he was a relatively senior businessman in his earlier incarnation (that said, he self-deprecatingly and amusingly pointed out that he was the only innumerate treasurer of one of the UK's biggest companies, and his employer, Enterprise Oil, paid someone to check all his numbers).

Also, he is a member of the influential parliamentary commission on banking standards, although his remarks to the Christians in Parliament All Party Parliamentary Group were personal, rather than representing those of the commission (I should perhaps point out that I was the token non-observant Jew on the panel that then responded to the Archbishop's reflections).

But perhaps more germanely, the UK's economic malaise shows no signs of being fixed any time soon by the supposed experts in the Bank of England or Treasury, so there may be a case for looking elsewhere for wisdom - and it is no longer eccentric to argue that what went wrong in the financial system was as much ethical as technical.