Austerity: Views across Europe

- Published

Voters' opposition to continuing cuts is mounting in several eurozone countries

Are the European Union's political leaders now changing their austerity policies in the face of growing popular opposition in some countries?

This week, the European Commission's President Jose Manuel Barroso said that he thought the policy had "reached its limits".

BBC correspondents in four European countries highlight the current state of political debates in Germany, France, Italy and Portugal, and look at whether or not governments and voters are yet ready to decisively move away from austerity.

Austerity 'painful but correct', Steve Evans in Berlin

In Germany, the austerians rule. This week, economy minister Philipp Roesler conceded that reining in spending was painful but insisted it was the right course: "On this point, this government will always remain firm."

In the US and Britain, economists argue over whether government spending is the best way of prompting depressed economies into life.

It is an echo of the argument in the 1930s between "orthodox economics" and the new economics of John Maynard Keynes who argued that governments needed to spend when interest rates were at rock bottom and there was substantial slack in the economy.

In Germany, that argument did not happen. The politics of the 1930s in Germany were different, so today there is no Keynesian tradition.

There are some dissidents, particularly among economists associated with trade unions, but not enough to dent the consensus that balanced budgets are the beginning and end of economic policy.

Chancellor Angela Merkel said that they were the way to ensure growth: "We need to find a way to have solid finances and of course growth at the same time."

Whether that combination is possible is debated hotly outside Germany but not inside it - and certainly not before the election in September.

Reforms 'too severe', Christian Fraser in Paris

Francois Hollande, pledged to reduce unemployment by the turn of the year but after two quarters of stagnant growth it is hard to see how the trend can be reversed.

The experts believe the economy would need to show annual growth of 2% to put a significant dent in the figures - the prediction for growth this year is 0.3%.

President Hollande is under pressure to slow his reforms

In a bitter irony, the only place to have announced any major hiring plan recently is the national employment agency, which said last month it would take on 2,000 extra staff.

Like the rest, France is buffeted by the ill winds from southern Europe. The crisis in Greece and Spain has had a dramatic effect on manufacturing, particularly the car industry - a major employer.

Perhaps it explains why Mr Hollande, since his election, has stood as the main bulwark to Germany's austerity. But at home the figures present him with a problem. Think of Mr Hollande as a social democrat.

There is a sizeable chunk of his party that are much further to the left and they believe the level of cuts and the pace of reform is too severe.

Eurosceptics gain ground

The key issue is labour reform. The government has made a start; it will be easier for factories to scale the workforce and their salaries to demand. But it is still too expensive to do business in France, and the tax horizon is ever changing.

If unemployment continues its inexorable rise then perhaps Mr Hollande's party will have no option but to grasp the nettle. But to do that they may need to convince the people first.

Next Sunday, to mark the anniversary of Mr Hollande's first year in power, thousands are expected to march in Paris with Jean-Luc Melenchon and his far-left Front de Gauche.

On the other extreme, polls suggest there is no longer a majority in France who think the far right Front National is dangerous; 47% see it as a threat while 47% do not.

Across the EU it is the eurosceptics, those who stand against globalisation, like the two extremes in France, that are gaining traction.

Jose Manuel Barroso questioned this week whether the pace of austerity was "sustainable socially or politically". There are very few on the left of Mr Hollande's party who would disagree with that.

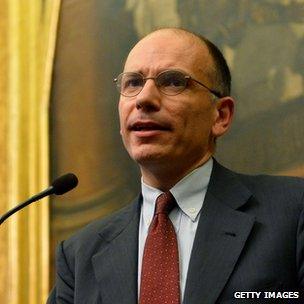

An 'unbearable emergency', Alan Johnston in Rome

The man currently trying to put Italy's new government in place, Enrico Letta, has made clear that he believes the country has endured more than enough austerity.

Austerity is no longer enough, says Italy's new prime minister

Mr Letta, of the leftwing Democratic Party, said his priority would be tackling the "unbearable emergency" of the economic crisis here.

He spoke of the suffering caused by business closures, unemployment and growing poverty.

And when it came for the search for answers to all this, Mr Letta said "too much attention" had been paid to the strategy of austerity - it was not enough any more.

Mr Letta's opponents on the right of the political spectrum agree. The former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi made a promise to reduce the tax burden a central part of his election platform.

He has described the austerity measures imposed by the outgoing, technocrat government as excessive and disastrous.

And just the other day I listened to the owner of a small upholstery workshop in the heart of Rome complain bitterly about the bleakness of the business climate.

Entrepreneurs like him would very much like to see the tax man back off, and a freeing up of spending that might to lead to growth, and better days.

Democracy 'at risk', Alison Roberts in Lisbon

In Portugal, the effects of austerity, particularly on unemployment, have prompted some to warn that democracy itself is at risk.

Portugal's democracy is under threat, say some

Vasco Lourenco, one of the army officers who helped end decades of dictatorship in 1974, with a coup that ushered in free elections and social reforms, was among several leading figures who refused to take part in official ceremonies this Thursday to mark its anniversary.

"Those in power are destroying everything 25 April represents, what was achieved," he told the BBC.

"People haven't realised it yet but it's no longer the welfare state that's at stake but democracy, because when the welfare state is destroyed it makes democracy impossible."

Though the right-of-centre coalition has a comfortable majority in parliament, cracks have appeared between its two parties, as protests against austerity have multiplied.

Yet the government, which from the start declared itself ready to "go beyond" measures agreed with international lenders, has never lobbied openly for an easing of its bailout targets.

'It is a systemic problem'

Troika officials last month recommended that Portugal get an extra year, to 2015, to bring its deficit below 3% of GDP.

But the finance minister, Vítor Gaspar, last week played down comments by the president of the euro group, Jeroen Dijsselbloem, suggesting the targets might be eased further given Portugal's "very tough" situation.

This was, according to Mr Gaspar, a "recognition" of Portuguese efforts but not a sign that renegotiation was imminent.

But even economists who stress the need to cut deficits say giving countries like Portugal more time is not enough. According to Vitor Bento, a former Treasury Secretary and a member of the council of state which advises Portugal's president, it is now clear the EU's "piecemeal" approach to indebted countries cannot work.

"At this stage it is not a sum of individual problems, it is a systemic problem," he said.

"It is replicating the mistake of the 1930s, to extend austerity even to surplus countries. Europe needs to concert an expansionary programme in order to promote growth."

There are signs EU officials are coming around to that view, he said, but the process is slow because many decision-makers are involved, all facing different political constraints.

- Published26 April 2013

- Published26 April 2013

- Published26 April 2013

- Published25 April 2013