How under-funded is lung cancer research?

- Published

- comments

Funding for lung cancer research is a fraction of that for other cancers

The Today Programme this morning highlighted a new initiative to coordinate lung-cancer research in London, with a view to increasing the availability of targeted, genetically personalised therapies for lung-cancer, external.

As you may know, this is an issue close to my heart, because my wife, the writer Sian Busby - a lifelong non-smoker - died of lung cancer at the age of 51 in September (which is why this is a slightly different blog from many I write).

So how under-funded is lung cancer research? This is an issue I looked at in a recent film for the One Show, but here is a bit more granular detail.

The first set of stats relate to how lethal it is.

Stephen Spiro, deputy chair of the British Lung Foundation : Low public resonance for lung cancer

Lung cancer accounts for around 13% of all cancers in the UK and 22% of cancer deaths, according to Mick Peake, the clinical leader of the National Cancer Intelligence Network.

So that's 42,000 new cases identified every year, and around 35,000 deaths.

Survival rates

To put that into some kind of context, the next biggest cancer killer is bowel, which accounts for just under 16,000 mortalities per annum and then breast, which kills under 12,000 a year.

What is also striking, and horrifying, is how quickly lung cancer kills sufferers.

Recent figures from the Office of National Statistics show that 83.3% of breast cancer sufferers are alive five years after diagnosis, just over 51% of bowel cancer sufferers live at least five years and 79% of prostate cancer sufferers survive five years.

In stark contrast, the five year survival rate for lung cancer is 8.8% for women and 7.4% for men.

Here is perhaps an even more chilling number: according to the ONS more than 70% of lung-cancer sufferers are dead in less than a year after diagnosis.

Now according to experts, such as Mick Peake, there are two reasons why lung cancer is such a savage killer.

One is that we are lousy in the UK at catching and diagnosing the disease before it becomes inoperable: cutting the cancer out through surgery is still the most effective way of prolonging life.

For reasons which the clinicians say are hard to fathom, parts of Scandinavia are significantly better at achieving early diagnosis of the disease - so lung-cancer sufferers there have much greater life expectancy than in the UK.

Prevention

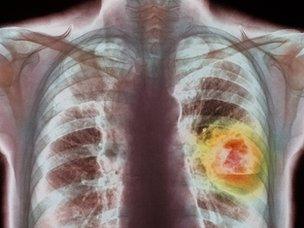

The simple thing that needs to happen, according to the experts I filmed for the One Show, is that those who have a prolonged cough - whether smokers or non-smokers - need to be sent for an X-ray on a more routine basis than currently happens in the UK.

The second reason why lung cancer is such a killer is that funds spent on research are a fraction of what they are for other cancers.

The main source of data on this is published by the National Cancer Research Institute, which receives information on cancer research spending from 22 organisations responsible for most cancer research in the UK.

Those who supply this information include Cancer Research UK (the most important research organisation), the Department of Health, Wellcome Trust and the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry.

This showed that in 2012, breast cancer received research funding of £41m, Leukaemia received research funding of £32m, bowel cancer received £35m, Prostate cancer got £21m and lung cancer - remember it is the biggest killer - got less than £15m.

And nor was 2012 untypical. Lung cancer has received significantly less than these other cancers have secured for research in every one of the 11 years of data published by the NCRI.

Historic reasons

There is a starker way of seeing this funding disparity.

Breast cancer receives just over £3,500 of research funding per death from the disease. Leukaemia receives over £7000 of research funding per mortality.

Lung cancer receives just over £400 per death.

So why has lung cancer research received so little funding?

Part of the explanation, historically, has been prejudice - according to researchers struggling to win research backing for lung-cancer projects.

There has been a perception that lung cancer sufferers have only themselves to blame, because they've smoked all their lives, and they tend to be old.

But this perception is wrong. The median age of diagnosis for lung cancer is 72, but with 42,000 diagnosed every year there are many thousands of sufferers who are much younger.

Non smokers

Of course there is a strong causal link between smoking and lung cancer. But is depriving smokers of help and hope tantamount to saying that addicts of all sort should be left to rot - which most people presumably say would be an appalling attitude?

However experts have also said to me that they have historically over-estimated the link between smoking and lung cancer.

Mick Peake, for example, says that around 10% or men and 15% of women who have the disease are people - like my late wife - who have never smoked. Others say that around 20% are never smokers.

So that is, as a minimum, more than 5,000 new cases per year in people who have never smoked and around 4250 deaths.

Resources

Here is the thing: the total amount of lung-cancer research in the UK equates to £3,500 per never-smoked lung cancer death, more or less the same as for breast cancer - which you might see as implying that as a society we have chosen not to devote any research resources to saving smokers.

Even if you think that is a correct societal judgement, as was pointed out on the Today Programme, many thousands of lung cancer sufferers gave up smoking years even decades before diagnosis.

However, it is not just stigma that has led to the under-funding of lung cancer. It is also that with so many sufferers being diagnosed too late for surgery, there hasn't historically been as much tissue available to researchers to carry out the kind of genetic research necessary to develop effective targeted treatments.

Which is why any serious progress in treatment and care of lung cancer requires a combination of better and earlier diagnosis with a more adequately funded research effort.