How Estonia became E-stonia

- Published

Ancient and modern: Estonia is preparing for a digital future

In some countries, computer programming might be seen as the realm of the nerd.

But not in Estonia, where it is seen as fun, simple and cool.

This northernmost of the three Baltic states, a small corner of the Soviet Union until 1991, is now one of the most internet-dependent countries in the world.

And Estonian schools are teaching children as young as seven how to programme computers.

Estonia's e-revolution began in the 1990s, not long after independence. Toomas Hendrik Ilves, then the country's ambassador to the United States, now Estonia's president, takes some of the credit.

There's a story from his time in the US that he is fond of telling. He read a book whose "Luddite, neo-Marxist" thesis, he says, was that computerisation would be the death of work.

The book cited a Kentucky steel mill where several thousands of workers had been made redundant, because after automatisation, the new owners could produce the same amount of steel with only 100 employees.

"This may be bad if you are an American," he says. "But from an Estonian point of view, where you have this existential angst about your small size - we were at that time only 1.4 million people - I said this is exactly what we need.

"We need to really computerise, in every possible way, to massively increase our functional size."

Online schools

So Estonia became E-stonia - a neat Ilves joke. And with the help of a government-backed technology investment body, called the Tiger Leap Foundation, all Estonian schools were online by the late 1990s.

President Ilves saw the online economy as an opportunity for a small country

Through Tiger Leap, they have been teaching programming at secondary level for some time. But their latest project is to introduce the concept to children earlier, when they enter at the age of seven. So far, they have trained 60 teachers to teach the first four year groups.

"By next September, when the new school year begins, I hope every school finds it to be important to integrate programming in their classes," says Tiger Leap's Ave Lauringson, who is in charge of the project.

In a newly-built, yellow-painted school in Lagedi, outside the Estonian capital, Tallinn, this can already be seen taking shape. A class of 10-year-olds are designing their own computer games, supervised by information and communications technology (ICT) teacher Hannes Raimets, a slight, quietly-spoken 24-year-old, a child of the first e-generation.

"I think teaching them to programme has lots of benefits. It helps the children develop their creativity and logical thinking," he says. "Also, it's fun, building your own game. "I think it's their favourite subject at school," says Mr Raimets.

What is also evident is that computer programming, at least at a basic level, just isn't that hard.

President Ilves makes the same point. Born in Stockholm of Estonian parents, he grew up and attended high school in the US. He learned programming at 13, as part of an experimental maths class, and says it helped him to pay his way through college.

"I don't think programming computers is such a deep, dark secret. I think it's strictly logic," he says.

"Here in Estonia, we begin foreign language education either in Grade One or Grade Two. If you're learning the rules of grammar at seven or eight, then how's that different from the rules of programming? In fact, programming is far more logical than any language."

Folk digital

President Ilves argues that education reforms take 15 or 20 years to show an effect. He feels this point is proved by the large number of technology start-ups for which Estonia today is attracting attention.

One of these is Frostnova, whose chief executive, Mikk Melder, is 25. His company has designed a game for primary school children called Ennemuistne, drawing heavily on local folklore and myth.

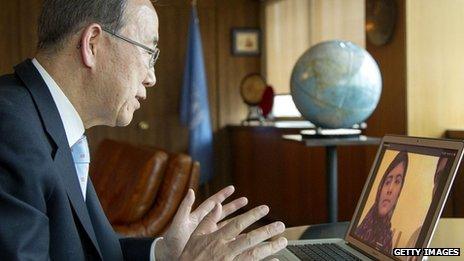

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon using Skype, an Estonian invention

Mr Melder says he visited local museums to make sure the architecture depicted is strictly accurate. Players can dress their characters in traditional costume and make them dance a uniquely Estonian jig.

"This is the ultimate purpose of the game," he says. "To bring something old, preserved and traditional into today's world, into the digital age."

Rather better known is Skype, an Estonian start-up long since gone global.

Skype was bought by Microsoft in 2011 for a cool $8.5bn, but still employs 450 people at its local headquarters on the outskirts of Tallinn, roughly a quarter of its total workforce. Tiit Paananen, from Skype, says they are passionate about education and that it works closely with Estonian universities and secondary schools.

"Your capability not only to use, but also to create IT components will give you a competitive edge," says Mr Paananen. He is happy to hear that they are now starting even younger.

"Skype has kicked off a wave of technological innovations in Estonia and all these knowledge-rich, highly-paid jobs will need those bright heads for the future."

Online voting

Estonians today vote online and pay tax online. Their health records are online and, using what President Ilves likes to call a "personal access key" - others refer to it as an ID card - they can pick up prescriptions at the pharmacy. The card offers access to a wide range of other services.

All this will be second nature to the youngest generation of E-stonians. They encounter electronic communication as soon as they enter school through the eKool (e-school) system. Exam marks, homework assignments and attendance in class are all available to parents at the click of a mouse.

The Baltic country sees technology as part of its cultural independence

"For most kids in Estonia, eKool is their first connection to ICT," says eKool's chief executive, Sander Kasak.

"They will be at school for 10 to 12 years, so they'll be learning about technological improvements all the time. So you could say eKool is not only a technological partner, but also an educational partner."

For Mairi Tonsiver, whose 11-year-old son Uku is a student at Lagedi School, eKool is a life-saver. He has just spent three school days at home because of sickness, but by checking online, his mother can find out exactly what he has missed and needs to catch up on.

"It was much more difficult and much more time-consuming when we didn't have eKool," she says.

"And your kids can't now make the excuse that they didn't write down what homework they have to do, because now you can just go to the computer and check it."

Uku says he wants to be a cosmonaut. Designing computer games is probably not a bad way to start.