What should the International Monetary Fund say to the UK?

- Published

The good friendship between Ms Lagarde and Mr Osborne is no secret

Here's a question: When a male friend refuses to concede that he may have taken a wrong turn, what is the tactful thing to do?

That, more-or-less, is the question facing Christine Lagarde, head of the International Monetary Fund, as her team of economists arrives in London on Wednesday for a regular annual visit to gauge the state of the UK economy.

It is no secret that Ms Lagarde and the Chancellor, George Osborne, get on well.

In her former role as French finance minister, the glamorous and flawlessly Anglophone Ms Lagarde once even made an impromptu appearance on Newsnight alongside Mr Osborne, whom she just happened to be meeting for dinner that evening.

In 2011, following the humiliating resignation of the former (and also French) managing director of the IMF, Dominique Strauss-Kahn, the British chancellor wholeheartedly backed the ascent of his "good friend" to the IMF helm.

Ms Lagarde seemingly returned the favour later that year, as the IMF backed Mr Osborne's ambitious plans to slash government spending.

Falling flat

Yet, if there is one outcome from this week's visit that is reasonably certain, it is this: The IMF will tell the Treasury that it has taken a wrong turn.

More specifically, it will say that the UK government needs to slow down its austerity plans big time, and perhaps that it needs to consider a Plan B, in the form of a more aggressive ramping up of publicly-funded investment, to boost the economy.

Indeed, this was pretty much the message delivered 12 months ago, after the IMF's last annual visit to our shores - not that anyone much noticed at the time.

The Fund's "Article IV" write-up last May explicitly stated that, external:

the UK economic recovery had stalled

the government should shift more of its spending to things like building infrastructure, to help perk things up

if the economy continues to flatline, then austerity will need to be slowed down

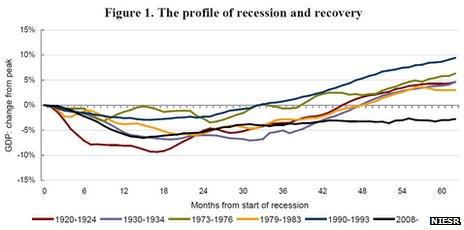

Since May 2012, the economy has continued to flatline, external.

What nobodies expected

What is more, this year's review comes after a fairly public change of heart at the IMF about the merits of austerity in general, and not just in the UK.

The instigator of this change of heart has been another French citizen, the Fund's chief economist, Olivier Blanchard.

He has been churning out research notes over the last 12 months, external pointing out how government spending cuts throughout the industrialised world have had a much worse impact on economic growth (or "multipliers" in economics lingo) than anyone had expected.

That "anyone", by the way, means anyone inside those governments.

Outside those governments, plenty of economists of a more Keynesian bent had fully expected spending cuts to severely depress Western economies, pointing to the following three reasons:

The US, UK and eurozone have just suffered serious financial crises, leaving many households and companies over-indebted, and therefore keen to cut their spending in order get their finances back under control

Normally central banks help out these struggling borrowers by cutting interest rates, but now interest rates have fallen as close to zero as Western central banks feel comfortable with, and it is still not enough

In these circumstances, if the governments of the US, UK and eurozone also all try to cut their spending at the same time, the whole exercise becomes self-defeating, because virtually all economic activity ultimately depends on somebody actually spending money

Sugaring the pill

Mr Blanchard has already been very explicit in his advice to Mr Osborne, telling the BBC in January that the chancellor should rethink his austerity plans.

More recently, as the IMF cut its forecast for UK economic growth this year to 0.7%, the chief economist went further, saying that to tolerate such a weak economy was like "playing with fire", external.

That boldness may be because Mr Blanchard now enjoys the backing of his boss.

Mr Blanchard has accused the chancellor of "playing with fire"

In April, a somewhat cagey Ms Lagarde herself told the BBC that the Treasury may have to give "consideration to adjusting by way of slowing the pace" of spending cuts, given that "the growth numbers are certainly not particularly good".

To be clear, nobody at the IMF is calling for a full reversal of austerity - unlike a certain vociferous economist across the Atlantic, external - but their report is still likely to prove politically awkward for a chancellor who has shown every sign of sticking to his guns - or should that be axe?

Mr Osborne has already put in a pre-emptive response to the IMF.

"The priority for most advanced economies is still to restore fiscal sustainability," he told the Fund last month, external - in other words, wavering now risked undermining hard-won market confidence in the government's finances.

Rather than calling on the UK government to go slow on its spending cuts, he in effect suggested the IMF instead lean on those troublesome "surplus economies" - code for China and Germany - to do more to increase their spending on imports from the UK and other perennial borrower nations.

So, to sum up, what can we expect from this week? The IMF's basic message is already fairly clear. And so is the chancellor's likely response.

All we are really left with is that question of tact.

In other words, should the IMF seek to publicly berate Mr Osborne - giving ammunition to his political opponents?

Or should the Fund downplay the disagreement, making it that much easier for Mr Osborne to simply ignore them?

- Published19 April 2013

- Published16 April 2013