Protecting that great idea with a patent

- Published

Mark Stadnyk is now finding it more difficult to make patent applications

Mark Stadnyk's inspiration for an adjustable motorbike windshield came from being "beat to death" by wind and turbulence when he rode his new bike.

But after coming up with the idea for a system of gears and brackets, it took rather a while to get a US patent.

"It wasn't that difficult in terms of the work [needed to apply]," he says. "I got an attorney to prepare the paperwork and an artist to prepare the drawings to patent office standards.

"Then it was a matter of waiting for about two and half years for the first patent, and another two years for the second one."

While waiting for the first patent, Mr Stadnyk developed and refined his product, which he has called the RoboBracket, turning it into a viable product.

He now employs seven people at MadStad Engineering in Florida, which he launched in 2006, and his US manufactured windshields sell for under $300 (£197). His annual sales total more than $500,000.

Mr Stadnyk said that despite the long wait to get the patent, "there was no dispute that this was something new and unique and patentable."

But in March this year the US government changed the rules.

Idea germ

To secure a patent for his next idea (a cosmetic product), Mr Stadnyk won't have to prove he is the first inventor, he just has to make sure he's the first inventor to submit the paperwork.

He says that could lead to multiple filings, making it more expensive and difficult for small businesses like his to compete with corporations armed with teams of lawyers.

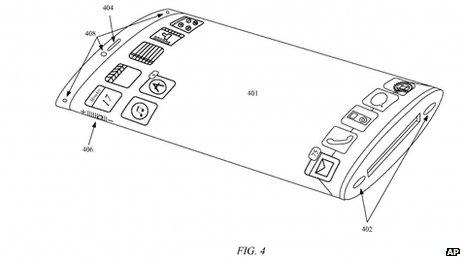

Apple has been involved in a number of patent battles in recent years

Depending on the type of application, securing a single patent can cost between $3,000 and $10,000 in legal fees and a further $2,000 to $5,000 in government processing fees.

"My idea might just be a germ of an idea and not developed. But I file because I'm afraid someone else will file first, [even though] I've not had time to experiment to see if it actually works or will sell," he says.

"In the next few months I might find that it's not going to work the way I want and have to change it. That means I have to file again."

'Wait and see'

The first-to-file regulation is part of the America Invents Act, which is aimed at streamlining the patenting process and bringing the US in line with patent laws in other countries.

Elizabeth Dougherty, director of inventor education, outreach and recognition at the US Patent and Trademark Office, acknowledges small business concerns, but says it's too early to tell whether they're justified.

"We have to wait and see," she says. "Some of these procedures are so new and are just being rolled in for the first time; it's difficult to know what the true case will be."

She says the act does offer tangible benefits to some small businesses and lone-inventers, in the form of greatly reduced patent application fees. And she says US businesses will find it easier to partner with companies abroad because the patent laws are now more compatible.

'Eureka moment'

The America Invents Act also aims to give businesses better access to the expertise found in many US colleges and universities.

British designer James Dyson successfully defended his vacuum's patents in the early 2000s

Education institutions contain a wealth of research that often goes no further than the classroom. But small businesses are being encouraged to draw on these hubs of knowledge when developing an idea. And many small business themselves are formed as a direct result of student research.

"It's about making science useful," says Mark Crowell, executive director of University of Virginia innovation in Charlottesville.

"The old days when one sat in a garage or alone in a lab and had that eureka moment - it happens - but it's no longer sufficient. You need people who understand markets, patent landscapes and finance and how to make something actually work once you've had the idea."

He says securing intellectual property (IP) ownership has become increasingly challenging because of the volume of open-source knowledge and the huge number of existing patents. Investors often demand patents before they'll fund further research or development.

"It's changed the nature of what we do. We discuss IP for new drugs earlier in the day than we did 25 years ago. Before, if we could just get a patent on the initial compound, we felt we were home free. Today we are more sophisticated, and because of the knowledge that's out there, it takes a lot more."

Defensive applications

Medical patents are often criticised by some groups for preventing cheaper generic drugs

Some 565,000 patent applications were filed in the US last year and the US Patent and Trademark Office is struggling to keep pace with the backlog.

"The sheer volume speaks to the creativity and status of innovation in America," says Ms Dougherty. "It's very positive. We haven't seen a dramatic decline with the change in law or because of the economy."

But Randolph Smith, owner of Washington-based law firm Smith Patent Office, says 95% of patents will never leave the drawing board. Large companies in particular obtain them as a defensive measure to prevent competitors from developing a similar product.

And he warns that small businesses must stay abreast of patent law changes if they want to stay competitive.

"A recent survey showed that only 9% of small businesses realise we've had the biggest change of patent law in the last 50 years," he says.