Press rewind: The cassette tape returns

- Published

VIDEO: The music and machinery spurred by the cassette's resurgence (Produced by the BBC's David Botti)

The humble cassette tape, a happy memory for many music fans of a certain age, has staged a comeback for one Canadian company.

The first order came in 1989: 10 cassettes. With that began Analogue Media Technologies, a company created to help bands market their music.

Musicians would bring finished master recordings and graphic design templates, and Analogue, now also called Duplication.ca, would turn those materials into slickly produced albums, complete with labels, cover art and liner notes, ready for sale or distribution.

"We've changed products depending on what's been in style and what the demand is for," says Denise Gorman, part-owner of the Montreal-based company.

It started with cassettes and vinyl, but then the trends shifted towards CDs, then DVDs and Blu-ray.

Now, they find themselves returning to the medium that started it all.

"We're back to cassettes as one of the main attractions," says Ms Gorman.

Analogue now says that cassette recordings make up 25% of the business. That is quite a change from five years ago, when cassette tapes seemed to be going the way of the defunct 8-track cartridge - the music format that was popular in the 1960s and 70s.

Fiscally sound

Audio purists love the analogue sound that comes from the classic cassette.

"Digital will always be ones and zeros," says Fernando Baldeon, a sales consultant at Analogue. "Analogue is still the best sound from a recording."

Vinyl, the purist's darling, has that sound, but it also has a hefty price tag - C$14.10 ($13.80; £9.09) per record for a set of 100, compared to C$1.29 for cassettes. Although cassettes are still slightly more expensive to produce than CDs, they add value for many of what Mr Baldeon calls "lo-fi" bands: punk, hip hop, metal and experimental groups.

"Clearly MP3s exist," says Craig Proulx, one half of the Ottawa-based record label Bruised Tongue. "I get it. I have an iPhone. But where's the fun in that?"

Bruised Tongue mostly produces punk bands, and Mr Proulx says the do-it-yourself aesthetic of the music make a good fit for cassette tapes. But the decision for him isn't just artistic, it's financial.

"In the past I've pressed records myself and they're nothing but trouble," he says.

The minimum number of records needed to complete a small order was still too much for him to sell. Tapes can be made quickly and cheaply without amassing too much overhead.

"Working on a local level, releasing cassettes is what makes sense."

Global appeal

Mr Proulx says he is part of an international community of local music producers and do-it-yourself fans who are all turning to cassettes to spread their music.

Denise Gorman says the firm is well positioned to serve customers as trends develop

And indeed, Analogue sees business from around the world.

It has cornered the market in Canada and attracts international clients, even in places such as the US, where other companies offer cassette duplicating services. But because the business is small, Analogue is able to offer more flexibility and faster turnaround times than some competitors.

"Small businesses are in a unique position to take advantage of trends because they can move quickly," says Helena Yli-Renko, associate professor of clinical entrepreneurship at the Lloyd Greif Center for Entrepreneurial Studies at the University of Southern California.

They are also better placed to serve a niche market, she says. Small companies such as Analogue can see big profits from filling a niche - profits that might be negligible to a huge conglomerate working with more mainstream customers.

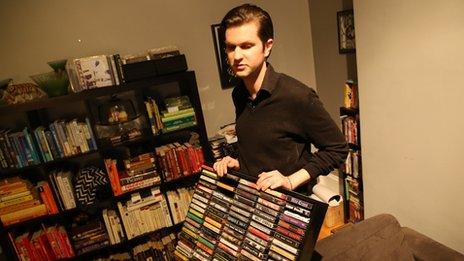

The variety of colours and printing options makes cassettes a popular choice for bands looking to be distinctive

The trick is to find out how to capitalise on these niche trends while also being aware that they could fall out of fashion next week, replaced by kids asking for their music on USB flash drives, or via digital download codes printed on Frisbees.

"You don't want to get into the business of imagining the clock is turning backwards and this is a permanent phenomenon," says Paul Kedrosky, a senior fellow at the Kauffman Foundation, a non-profit organisation that runs programmes for would-be entrepreneurs.

Staying the course

"When small businesses are looking at whether to go for an opportunity like this, the first test is, 'Is this in line with what we do as a company? Does this serve the same customer needs?'" Ms Yli-Renko asks.

In Analogue's case it does. By serving existing customers well, it is able to expand its client base.

"We get a lot of referrals," says Ms Gorman. "In Australia or Japan, we'll suddenly see a whole bunch of orders at the same time." Because the clients exist in such tight-knit communities, word spreads quickly once one band finds a reliable source of niche products it needs.

Still, it's difficult to say how long a company can count on revenues from a fad.

Craig Proulx says he has discarded scratched CDs, but still has cassette tapes from his childhood.

Mr Kedrosky says companies profiting from a new trend need to ask if it is transient or evidence of something more fundamental? "If it's just faddish, and gone in six months you don't want to invest too much effort," he says.

Since Analogue started as a company that makes cassettes, it is well positioned to capitalise on the fad without having to invest in new equipment or inventory.

Michelle Gorman says that as long as bands want to package their music, Analogue will be prepared to meet the next trend.

"I don't know what's going to take off next, but we'll be prepared for it," she says. "That's how I work. We roll with whatever the client wants, that's how we try to satisfy our clients and that's how we bring the best products. We give them what they want, and we have the tools to do that."