3D printing: A force for revolutionary change

- Published

- comments

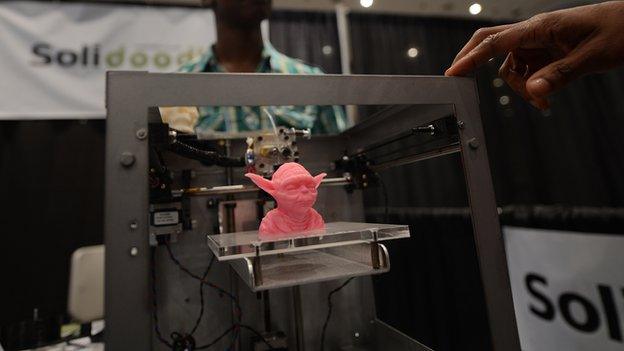

May the prints be with you: A recent example of a 3D-printed object

It was Neil Gershenfeld who introduced me to the potential of additive manufacturing, also known as 3D printing, getting on for 10 years ago, and I got very excited about its possibilities. And now, years later, here he is, trying to dampen my enthusiasm.

Professor Gershenfeld has been one of the stars of Massachusetts Institute of Technology MIT for a long time. I first encountered him at the famous MIT Media Lab nearly 20 years ago when he was part of a team investigating Things that Think: the wearable computer, for example.

Under its founder Nicholas Negroponte, the MIT Media Lab was one of the definers of the new digital era: a world where bits and bytes take over from atoms in many familiar activities and where everything that can be digitised will be digitised.

In 2002 Neil Gershenfeld spun off from the Media Lab something called The Centre for Bits and Atoms. It was inspired by MIT classes he had started in making things - physical things, not the computer software that had become such a large part of the MIT experience.

The classes continue: "How to Make (Almost) Anything" and "How to Make Something that Makes (Almost) Anything". They've been wildly successful; packed with hundreds of brainbox MIT students from many disciplines anxious learn how to use advanced machines to make things for themselves.

The Centre for Bits and Atoms is where I first encountered a 3D printer. They're not new: they've been around for 20 or 30 years, used by designers to make rapid prototypes of products they are developing.

It's a sort of extension of Computer Aided Design which has so transformed professions such as engineering and architecture.

You draw the design on a computer screen, and the data then drives a machine which spreads thin layers of plastic or metal powder on top of each other. Each layer is solidified by a sort of laser welder or sinterer; at the end of the process you blow off the unsintered powder and the object you drew on the screen is transformed into complex, intertwined three dimensional reality.

3D printing takes weeks or months off the design process, but for years it stayed as a prototype process, trying things out.

Now that's changing. Better techniques and materials are turning 3D printers into manufacturing operations - so-called additive manufacturers - as opposed to the cutting and grinding and sawing that has typified engineering up to now.

This is a great big step. It individualises industries which until now have been dominated by mass production. In theory, every single product can be different, made to measure, as operators learn how to make things with mixed materials on larger and larger scales.

In theory, it seriously reduces the need for factories, production lines, warehouses, transport around the world from great production hubs. Many things can be printed up for digital instruction in a neighbourhood print shop, and carried home under your arm, rather than shipped in container loads around the world.

Darker side

A student at the University of Texas managed to create a gun using 3D printing

In New York, I dropped in on a refurbished warehouse in Long Island City where a Dutch company called Shapeways is building a battery of 3D print machines to make things sent in by its customers -as data - over the Internet.

The products—lots of jewellery and individualised smartphone cases, but it could be anything—are then shipped back to them a few days later. 3D printing for people who don't want to spend upwards of $1,000 dollars on their own machine.

This is not necessarily nice. Sex toys are obvious personal 3D products. At least one American company is making headlines for printing guns and making the designs available to others. The authorities are investigating.

In theory this is a very disruptive change indeed, a new industrial revolution.

Neil Gershenfeld thinks journalists have got carried away by 3D printing

You might say that the development of printing ushered in the modern era 500 years ago.

In the same way, the combination of the internet, broadband-powered interactivity and the 3D printer could create a new nimble industrial era of individualised, localised goods escaped from the grip of huge manufacturing companies with vast capital investments and cumbersome making and delivery processes.

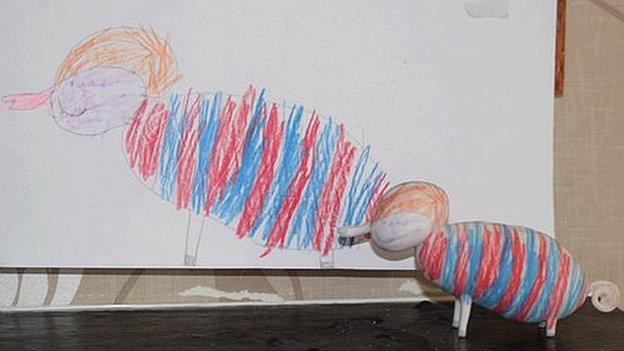

A great opportunity for entrepreneurs and start-up companies, these 3D printers. Turn an idea into a design, into a product almost instantly, and then reach an internet marketplace at the click of a mouse. Capitalism without capital, or without much of it. A new 3D world.

'Strange meme'

At least, inspired by Neil Gershenfeld, that is what I thought.

But the other month at the Centre for Bits and Atoms, he put a big shot across my bows.

"Three D printing is a strange meme that is being misrepresented in the press by people who don't actually use it", he said.

"You're pointing at me," I said. "You and your peers," he replied.

"Ouch!" I said, with some disappointment.

Neil Gershenfeld thinks that the press has got carried away with 3D printing, something which is interesting, but of limited application compared with all the things a creatively inclined person can do with the other machines.

Gaze on the products a 3D printer can make and you go a bit soft in the head, he thinks, especially when (like me) you have never used one in your life.

The thing is, what Neil Gershenfeld has at the Centre of Bits and Atoms is room after room of superb and expensive digitally driven machines that he hopes one day to compress into one quite small piece of kit for the home-based maker.

They're the components of what he calls Fab Labs, community fabrication centres where anyone can drop in and learn to use really advanced digital machinery.

Inspired by the MIT Centre for Bits and Atoms, there are now about 100 Fab Labs all over the world, including places such as Afghanistan, Belfast and Manchester.

Yes, they use 3D printers, but they are well down Neil Gershenfeld's list of priorities.

More useful, he says, is a computer-controlled laser cutter, a numerically-controlled milling machine for making big parts, a sign cutter, a precision milling machine and programming tools for low-cost high-speed embedded processors.

So 3D printing is not—according to one of the prophets of the new personal manufacturing age—going to change the world on its own.

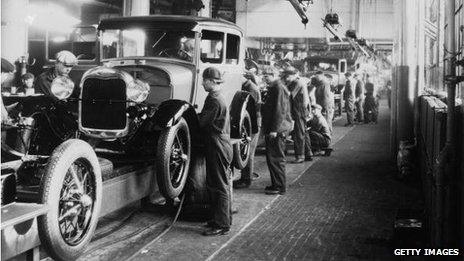

Mass manufacturing, like Henry Ford's production lines, may soon be replaced

Nevertheless, something is up. Professor Gershenfeld says that it's the suite of digital machines that in his words "blows up industry".

Just as personal computing transformed the computer industry, so many manufacturing corporations are going to be shoved aside by the personalisation of fabrication, by individualised goods.

Henry Ford's production lines have been the overwhelming model for manufacturing for the past 100 years. That predominance will soon be replaced by something much more individual, much more local, much more flexible.

And whatever Neil Gershenfeld says, I've still got a hunch that 3D printing is going to have quite a part in the revolution. Even though I have never done it.

In Business: New Dimensions is on BBC R4 at 8.30pm on Thursday 16th May, repeated at 9.30pm on Sunday 19th May.

- Published8 May 2013

- Published6 May 2013

- Published22 April 2013

- Published16 April 2013

- Published1 February 2013