How bust is Whitehall?

- Published

This government appointed a series of business people to sit as non-executives on the boards of Whitehall departments.

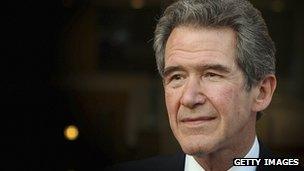

The so-called "lead" non-executive, the primus inter pares, is the former chief executive of BP, Lord Browne.

Tonight, in a speech to the Institute for Government, he will give a gloomy assessment from his ringside seat of the capability of Whitehall to deliver what's demanded of it.

"We now expect the civil service to deliver more. from a declining resource base, and with a staff which is being asked to do things they were not trained to do," he will say.

Oh dear.

He continues:

"Sometimes I feel that we expect the civil service to do anything that is asked of it, without the right behaviour or culture that comes from the appropriate incentives, pay, training or overall structure in which to perform."

He argues that the governance of Whitehall hasn't changed sufficiently from what was appropriate for the small, less complicated public sector of the nineteenth century - and he therefore believes the time is ripe for a "comprehensive and independent review of the civil service's structures, processes and lines of accountability".

It could of course be argued that he knows a thing or two, from painful personal experience, of the terrible consequences of a failure to adapt governance to changing circumstances.

At BP, he oversaw the massive expansion of the company through a series of huge takeovers, but arguably did not adequately adapt the company's operational controls and grip on potential risks - failures that came close to destroying BP in the Deepwater Horizon disaster, after he had left.

Strikingly, he argues that Whitehall needs to become better and more confident about talking out loud about its own failures.

He argues that the civil service is hopeless at learning from past mistakes. "Failure is frowned upon", he says, "rather than seen as an inevitable and desirable consequence of informed risk-taking".

That said, he doesn't believe civil servants are equipped to succeed, especially in the management of complex large projects. Despite concerted efforts to train them, they lack commercial skills.

So (and you will have heard this before from private-sector leaders) he wants more secondments from business into government, and fewer constraints on how and how much these secondees are paid.

However it is not just the civil servants he has in his sights, but everyone in the public sector with the power to take decisions.

What may resonate with many is his belief that policy-making based on trawling through all the evidence has gone too far.

By all means harvest the relevant facts and data, he says, but the best decisions require an intuitive or irrational leap of faith.

Which is another way of saying - and he is not the first to say this and won't be the last - that good government requires less timidity and more leadership.