A350: The aircraft that Airbus did not want to build

- Published

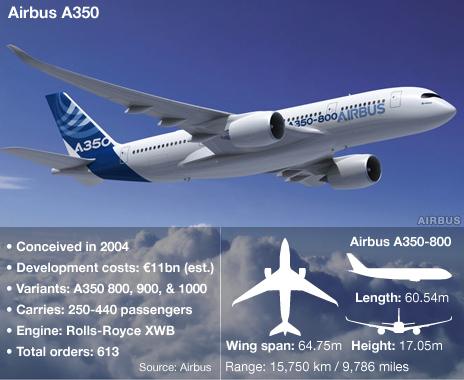

After many years on the drawing board and $15bn (£9.5bn) of investment the latest potential blockbuster from Airbus made its long-awaited first flight on Friday.

The A350XWB (extra wide body) is an aircraft which Airbus says will set new standards in fuel efficiency and environmental performance.

The long-range, twin-engined plane is being pitched as a direct rival to Boeing's radical 787 Dreamliner, another airliner which claims to have taken aircraft technology to new heights.

Yet, the A350 is also an aircraft that Airbus never really wanted to build.

Towards the middle of the last decade, the European manufacturer had its hands full preparing for the launch of its long-delayed A380 superjumbo.

The double-decker giant was a hugely complex machine, and its development costs were spiralling. So Airbus was reluctant to commit billions of dollars to another clean-sheet design.

But, Airbus needed a new product to take on Boeing's planned Dreamliner, which was already attracting a great deal of interest from airlines.

Unlike the A350, Boeing will have its Dreamliner on display at the Paris show

The Dreamliner was to be built using lightweight carbon composites, and to feature advanced aerodynamics in order to reduce fuel consumption and running costs.

The design Airbus came up with was based on its existing A330 model, but with a lighter fuselage, new wings and new engines, in an attempt to match the Dreamliner's fuel efficiency.

But potential customers weren't impressed. Among the fiercest critics was Steven Udvar-Hazy, then head of International Lease Finance Corporation, which buys huge quantities of aircraft.

A very powerful figure within the industry, he suggested publicly that the A350 as planned simply wasn't up to the job. Several airline chiefs agreed - and in mid-2006, Airbus went back to the drawing board.

The result is the aircraft that now stands on the tarmac at Airbus' headquarters in Toulouse, and it seems that airlines have already given it a sizeable vote of confidence.

State-of-the-art

More than 600 orders have already been placed, and more deals look set to be announced at next week's Paris Air Show, where Air France is reportedly considering the purchase of 25 A350s plus options for another 35.

Analysts say a first flight for the A350 has more than just symbolic value. It underlines to potential buyers that a complex industrial project is on target.

Theo Leggett takes a look at how the A350XWB is put together

Like the 787, the A350 is a radical machine. It offer airlines the chance to combine long-range services with improved fuel efficiency.

The fuselage is made of carbon fibre reinforced plastic, while many other parts of the aircraft use titanium and advanced alloys to save weight.

It also has state-of-the-art aerodynamics, and engine manufacturer Rolls Royce has produced a new custom-designed power unit.

Airbus claims that all of this means the A350 will use 25% less fuel than the current generation of equivalent aircraft. It also points out that noise and emissions will be well below current limits.

The market segment that the A350 is aiming at is set for huge growth, John Leahy, Airbus's chief operating officer, told the BBC. He estimates that some 6,500 of such aircraft will be required by the world's airlines over the next 20 years.

What's more, he thinks the A350 is pulling ahead of the Dreamliner. Mr Leahy said: "The A350 reached over 600 sales in much quicker time than the 787 ever did, so the markets have spoken for themselves in demonstrating overwhelming demand for the A350."

But as Boeing recently found with the 787, new and unproven technology can have its drawbacks.

In January, the Boeing flagship was grounded by regulators, little more than a year after entering service, after overheating batteries caused a fire on one aircraft and smoke on another.

The 787 was using lithium ion batteries, very popular in gadgets such as laptops and mobile phones, but never previously installed in a commercial aircraft. While they are light and can store a great deal of energy, they can also be prone to overheating.

Fly-past

After a rapid redesign, the 787 started flying again in April. Meanwhile, Airbus decided not to use lithium ion batteries in the A350 - which it had originally planned to do. Instead, it will stick with proven nickel-cadmium technology.

.jpg)

Rolls-Royce Trent engines will power the A350

But Airbus's caution over the A350's development may help to explain why the aircraft will not be making its public bow at this year's aerospace industry showcase, the Paris Air Show.

Not only is the show on Airbus's home turf, it is the 50th aviation trade fair in Paris since the first in 1909.

Airbus would have dearly wanted to have put its new toy on display there. But the company appears to have been very wary of rushing the new plane into the air.

Instead, it has been taking its time resolving glitches, away from the public eye. The first flight has come just too late to allow the A350 to join the party.

So on the Le Bourget airfield next week at least, Boeing will be able to steal a march on its rival. The 787 will be on prominent display, as the US manufacturer tries to rebuild its damaged reputation.

But there remains the tantalising possibility that the newly airborne A350 might at least make a fly-past.

And if it can do that, the A350 could just steal the show.