Phone boxes: Do we really need them?

- Published

Many phone boxes lie unloved and unused

The red ones may be design classics, but when was the last time you actually used a phone box?

Telecoms provider BT says only 3% of us have made a call from one in the last month, so it is planning to remove more than one thousand boxes this year.

Over the last decade it has taken away more than 33,000 payphones, well over a third of the total.

But some villagers in rural areas are fighting a rearguard action, saying they want their phone boxes back.

Last month, one such box was removed from the village of Pilton in Somerset, which is home to the Glastonbury festival.

Pilton had its phone box removed last month

BT says it gave the parish council a year's warning. And it left a notice inside the phone box, which it is also obliged to do.

"I understand that BT want to get rid of them because they're redundant, but for our village... it's history," says Sylvie Drake, a local resident.

In days gone by, music fans used to queue down the hill to use the phone box.

But now everyone has a mobile.

"It may have had its time as a means of communication, but it still feels wrong that they could just walk in and take it away," said Louise Butler, who lives a hundred metres from the spot where it used to be.

£1 a box

BT makes no apology for removing such boxes.

Some 33,000 payphones, more than a third of the total, have gone since numbers peaked in 2002.

And 1,000 more will go before the end of 2013.

On average, just one phone call a day is made from each of the 58,500 remaining payphones. In rural areas they are used even less frequently.

"Payphones in towns and cities are really well-used, with about 65,000 calls a day going through them," says Mark Johnson of BT.

"But in rural areas we've got 12,000 payphones that haven't made one call a month in the last 12 months," he told the BBC.

With 70% of payphones losing money, BT cannot afford to maintain such a large network.

It is encouraging communities to buy such phone boxes under its Adopt-a-Kiosk scheme. Communities pay just £1 to buy the box, and they can then use it as an information point, a library, or for storing a defibrillator, a device used by emergency crews to treat heart attack victims.

'Death of the phone box'

One of the strongest arguments for keeping phone boxes is that thousands of areas across the UK still have no proper mobile phone signal.

Officially 99.7% of UK homes and offices have mobile phone coverage from at least one service provider.

But the telecoms regulator Ofcom provides a map of so-called "not-spots", external, which shows that most counties in the UK still have areas where reception is poor.

For that reason the government is currently spending £150m to improve mobile infrastructure.

Some experts believe such investment will finally render payphones redundant.

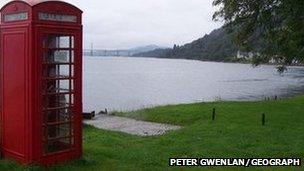

Villagers in Kilmuir formed a blockade to save their phone box

"Coverage is still a big issue, but that's being addressed by the phone companies, who are committed to a better signal in rural areas," says John McCann, who writes for the website TechRadar.

"That will really see the death of the phone box," he says.

In the meantime he holds up his smartphone outside a red phone box, and does a quick comparison.

"On my phone I can make calls, send text messages, browse the web, check out social media, send emails, and I can play games - whereas that thing over there, it just makes phone calls. So you can really see why it may well be doomed."

Women's Institute

But somehow we all just love a red phone box.

Tourists leaving Heathrow will probably buy shortbread in a phone-box shaped tin, exporting this oddity across the globe in a declaration that we Brits are still as self-confident and enduring as a bright red, solid-iron, 1936 industrial masterpiece.

The inhabitants of the Scottish village of Kilmuir showed just such affection for the work of designer Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, when, on hearing their phone box was to be removed, they barricaded their cars around it, to stop a lorry getting anywhere close.

While BT refused to leave the phone mechanism in place, villagers on the Black Isle near Inverness eventually did buy the box for a pound.

The quiet yet determined ladies of Toller Porcorum in Dorset have also fought a spirited campaign with BT to keep their phone box.

Ladies in Toller Porcorum have a rota to maintain their phone box

There is no mobile signal in the valley, and they argued that, even though few people were actually using the phone box, many walkers relied on it.

BT agreed to leave the phone, although they removed the coin box.

The box itself is now looked after by six members of Toller Porcorum Women's Institute, who have a regular maintenance rota.

They have even placed a vase of flowers inside.

"We dust the phone, take the spiders out, and we kill the flies that like to live there," said Pat Rutherford, a parish councillor who lives nearby.

"At Christmas we put in decorations: lanterns, sparkly things, and tinsel. But we're still battling with BT to keep it," she told the BBC.

Disappointment

Looking to the future, BT says it has development plans for many of its existing phone boxes.

Some of them already carry wi-fi equipment, to create hotspots for customers. Some 450 contain cash machines, and that number will be expanded. The company is also looking at making some of them into parcel delivery/collection points.

But sadly for the villagers of Pilton, BT cannot offer any good news about reinstating phone boxes that have already been removed.

"They were given every opportunity to adopt that kiosk," said Mark Johnson.

"Unfortunately that one has gone," he told the BBC.

"And we don't reinstall them."

- Published10 May 2013

- Published22 March 2013

- Published4 October 2012