When will banking ever change?

- Published

The government wants more competition in banking - but most of us are just too lazy to switch bank accounts

This is the year we are going to "reset the banking system", said chancellor George Osborne in a speech to JP Morgan workers in February.

And boy, does it need re-setting. Its rap sheet is long and inglorious.

"Irresponsible behaviour was rewarded, failure was bailed out, and the innocent - people who have nothing whatsoever to do with the banks - suffered", Mr Osborne curtly summed up.

The government's answer? Ring-fencing retail and investment banking operations; a strengthened regulatory structure; and the encouragement of "upstart" challenger banks to inject competition into a market where the "big four" High Street behemoths - Barclays, HSBC, Lloyds, and Royal Bank of Scotland - still control around three quarters of all UK personal current accounts.

So where are these challengers and how are they doing?

Convenience

Metro Bank, the first new High Street bank for 100 years, entered the market in 2010, and now has 19 "stores" across Greater London, with over 200 planned by 2020. Its main selling point is convenience, opening seven days a week.

Its US founder and chairman Vernon Hill certainly has form. He set up Philadelphia-based Commerce Bank in 1973 with a philosophy of attracting deposit-making "fans not customers" and sold it to TD Financial in 2007 for $8.5bn (£5.4bn). By then the bank had $50bn in assets and 500 branches.

Metro Bank is the first new bank on the High Street for 100 years

"The big banks in the UK operate like a cartel," Mr Hill told the BBC. "They overcharge and underserve. Metro is one of the new threats to their dominance."

But he admitted: "Setting up a bank in the UK is a complicated, difficult and capital-intensive endeavour."

Simon Hills, executive director at the British Bankers Association, argues that things have changed a lot since Metro began.

"It's got a lot easier in the last six months," he says.

This is largely down to a streamlined application and vetting process by the new Prudential Regulatory Authority, he maintains. New banks, particularly if they are offering simple deposit and current accounts, can set up business within six months with capital of just £5m, he says.

"They have to be able to show that if they go belly up they won't need a bailout."

And if they want to lend money their capital adequacy requirements are much less onerous in the first two years of operation, he added.

Off-the-shelf

But he concedes that an underdeveloped market in banking IT services makes starting up a bank in the UK more difficult than in the US, for example, where off-the-shelf systems are readily available. Vernon Hill concurs with this assessment.

Even if Metro's UK expansion plans stay on track - it has about 140,000 customer accounts so far - 200 branches is a pinprick in the side of Lloyds Banking Group, say, which will still have over 1,300 branches even after transferring 468 of them - including all Cheltenham & Gloucester branches - into a new separately floated bank, TSB, in the summer.

This imposition on Lloyds came courtesy of the European Commission, which approved £17bn of "state recapitalisation" during the financial crisis, providing the group shed some of its bulk.

The recent failure of the Co-operative Bank to buy 631 branches from Lloyds as part of this process was a considerable embarrassment for a government that had encouraged the deal. And now that Co-op plans to fund the gap by forcing bondholders to become shareholders and floating on the stock market - albeit still majority-owned by its parent - some are seeing the move as another nail in the coffin of the mutual ideal.

Virgin Money bought Northern Rock's remaining healthy assets in 2011

Full-service banking

Virgin Money bought the good bits of Northern Rock for £747m in 2011 and completed the integration of the two businesses in November 2012.

But it has just 75 branches, or "stores" as it also likes to call them, and has "no plans" to expand the network, relying primarily on the internet and call centres to service its four million-plus customers.

"Our ambition is to become a full-service retail bank to rival the big four," a Virgin Money spokesperson said, pointing to the bank's "very well capitalised and highly liquid" position.

But is this the triumph of hope over experience? Virgin Money still does not offer a personal current account, although it plans to launch one "before the end of the year".

The problem is that current accounts are notoriously expensive to operate, hence the need for the big banks to recoup costs by selling other products. Virgin Money is still debating whether to charge a monthly fee.

Similarly, Tesco Bank, which many analysts believe could provide serious competition to the big four given its existing national supermarket network and Clubcard database, plans to launch a current account, but not before 2014.

Its customers have bought 6.6 million credit cards, personal loans, savings, mortgages and general insurance products so far.

Switching

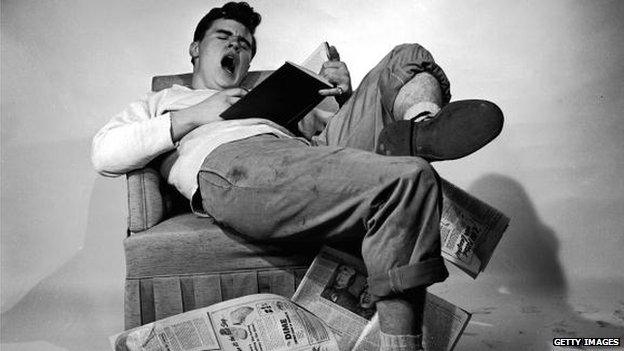

But the biggest barrier to increased competition, some argue, is not bureaucracy or capital adequacy requirements, it's us. We are just lazy when it comes to switching accounts.

"There's an awful lot of inertia out there", said David Black, banking specialist at Consumer Intelligence. "Current accounts are very sticky products. You need to offer something truly exceptional to encourage people to switch."

Most of us have had our bank account for more than 5 years

A recent survey by Consumer Intelligence suggested that nearly two thirds of respondents have had the same bank account for five years or more. It would take the introduction of cash machine withdrawal charges or monthly fees on credit balances to make most of us switch, it finds.

The government wants to make the switching process easier; from September a new law comes into effect stipulating that banks have to facilitate account switching within seven days.

And the EU's forthcoming Bank Accounts Directive is also aimed at increasing the transparency of bank fees and charges so customers can easily compare accounts and switch providers, including across borders.

But Peter Hahn, senior fellow and banking expert at the Cass Business School, is sceptical such efforts will have that much effect.

"People don't change banks much, and when they do it's usually for a negative reason - they're fed up with the service or the high charges," he says.

So what will work?

"The real game changer in UK retail banking will be when the likes of Google, Amazon or Apple decide to enter the market," he argues. "Amazon is already experimenting with lending to its small business customers in the US."

Until then, the big four look set to remain the big four for several years to come.