Iron Maiden's Bruce Dickinson on his airline ambitions

- Published

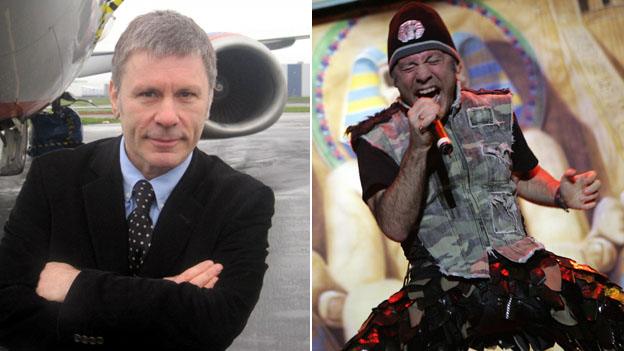

Bruce Dickinson in business mode at the Paris Air Show and doing his "part-time job" with Iron Maiden

Bruce Dickinson arrived for his BBC interview wet, hot, but in remarkably good spirits.

The lead singer with rock band Iron Maiden - and aviation fanatic - was at the Paris Air Show to unveil expansion plans for an aircraft maintenance business he started last year.

The usual chaos and gridlock, that have become an annoying inevitability of travelling to the show, were compounded by a lightning storm.

Mr Dickinson ended up abandoning his taxi on the motorway and walking a mile in the rain. But it has not dented his enthusiasm.

"It's great to be here," he says. "I've done Farnborough [the UK air show] but never Paris. It's all very exciting."

He left the show a few hours later, heading for Berlin where Iron Maiden's world tour continues. "But I should be back on Thursday," he says. Despite his love of all things aviation, Dickinson adds: "I'm here to do business, not watch the displays."

Doing deals

Last year, he set up Cardiff Aviation, a joint venture with business partner Mario Fulgoni, a pilot and airline executive.

They took over a fully-equipped former RAF maintenance facility at St Athan, just outside Cardiff. The site can park 20 narrow-body airlines, and the hangar is big enough to house a Boeing 767-300, just smaller than a jumbo jet. There is also a 6,000ft runway.

With an initial investment of £5m from a mix of government and private sources announced on Monday, the pair want to make it a centre for repairing and maintaining civil aircraft.

There are also plans to open a pilot training facility, and Dickinson is in advanced talks about setting up an airline leasing-cum-charter operation. It will be what is called an ACMI airline - providing aircraft, crew, maintenance and insurance.

He says: "Asia and the Middle East is going to be where the huge growth in aviation will be. But the smart way to start an airline is not to spend huge sums of money up front, but to come to companies like us.

"Our ambition [at Cardiff Aviation] is to create a sort of one-stop shop," he says. "A lot of maintenance facilities are closing, especially in Europe because of high labour costs and inefficiency. We have not inherited that."

Dickinson said his business is close to securing a deal to become the sole provider of maintenance to an aircraft leasing company, and he was in Paris to discuss possible contracts with airlines.

He says: "It's early days, but our business plan is perfectly achievable. We are already in profit and have no big debts. I think that's pretty good."

Engineering in his blood

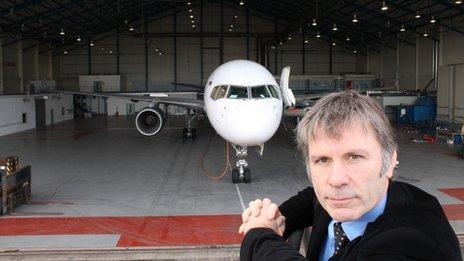

Dickinson, here at Cardiff Aviation, hopes to create many more jobs in Wales

The business employs about 80 people, though clearly if the expansion plans come to fruition that number will rise considerably, probably by many hundreds, he hopes.

There are complex certification procedures to pass, both for the maintenance operation and to start an airline. It will take time, he says, but things are progressing well.

Given the Iron Maiden fame, it's easy to assume that Dickinson's role in the venture is to open doors with prospective clients. "It helps," his business partner Fulgoni admits.

But it is clear that Dickinson loves being both an entrepreneur and involved in building something that could mean investment and jobs. Music, he said, is now a "part-time job" that brings in the money, he joked.

Dickinson went to his first air show aged five, and got his fascination with aircraft from his dad, an engineer, and uncle, who worked for the RAF. "Don't ask me to put up a shelf, but I love engineering."

And that was his cue to go off on a passionate five-minute rant about the failings of the educational system, and engineering itself.

"Teachers need to be more inspirational. But it's also up to engineering to make itself more interesting.

"Engineering stimulates the mind. Kids get bored easily. They have got to get out and get their hands dirty: make things, dismantle things, fix things. When the schools can offer that, you'll have an engineer for life," he says.

He got his pilot's licence in 1991, gaining more qualifications and experience so that he could fly bigger planes on longer journeys. He began flying Iron Maiden on tour, and then got a job with the now-defunct British World Airlines.

Later he became a pilot for Icelandic-owned charter airline Astraeus. That collapsed in 2011. "I was in the air when it happened, flying a group of pilgrims returning from Jeddah to Manchester," he recalls.

He does not do much piloting these days. Some of the shine has been taken off the job, because most modern aircraft are flown by computers these days, not pilots.

"You just need a pilot in the cockpit in case something goes wrong," he says.

"It's still a huge thrill to take off and land. But when you are in a plane, you are in the hands of the engineers. That's where it's at these days."

- Published17 June 2013

- Published21 November 2011