Jambo pesa! (Hello, money! in Swahili)

- Published

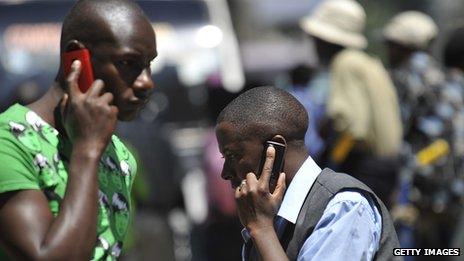

M-Pesa, money transfer services using mobiles, are used by half of Kenya's population

The last time I was in Kenya in 2007, it was pretty easy driving round the capital, Nairobi.

The cars jolted fairly steadily over the holes in the road; the place had the air of a rather provincial city: nice climate, nice people, a dark underside of criminality, but a bit slow.

Six years later, you notice the change straightaway, coming in from the airport at seven o'clock in the morning. Even then the traffic jams are accumulating, and they are going to stay in place all day and into the evening.

A journey to the suburbs takes at least an hour of uncertainty. By any standards anywhere, this traffic is notably dreadful.

Prosperity brings cars, and cars clog the place up, as they do almost everywhere else in the developed and developing world.

And one of the reasons for the new prosperity and the air of expectation in Nairobi is high technology entrepreneurship, which I actually encountered the inklings of on my first visit here, and did not exactly recognise.

In 2007, it was the so-called informal economy that hit you in the face: the vast number of roadside stalls hawking everything imaginable. A vibrant but little documented part of the Kenyan business scene that some people estimated contributed as much as 40% of the country's GDP.

The intensity of small-scale economic development was particularly evident in the vast Nairobi slum Kibera, said to be the biggest in Africa, though no-one can count how many people have settled there... something like 600,000, perhaps.

Food, drink, power, water and all sorts of other goods were all provided by an intricate network of private enterprise: local, small scale, cash on the nail.

Mobile phones usage grew much more quickly in Africa than in the West

Transforming communication

But back in 2007, something else was stirring.

I was in Africa to report on the explosion of mobile telephony that was transforming communications in the cities and the countryside in many African nations, and creating new business opportunities.

In Ghana, schoolgirls were putting themselves through college by selling airtime to customers without a phone by the side of the road.

In Kenya, not-for-profit organisations were using phones to tell village farmers the daily price in Kenya's markets of the crops they were harvesting: real-time information which undermined the grip of the middlemen who had been their sole buyers until then.

Hawkers could get prices from different suppliers, rather than depending on the one next door.

I saw this and reported it, and then I went to see the head of the largest mobile phone company in Kenya, Safaricom - then half owned by Vodafone and the Kenya government.

Michael Joseph told me about the huge take-up of mobile phones in Africa: far faster than the speed they had been adopted in the rich world.

Faraway people previously denied phones because they were never reached by copper wire in the ground (and never would be) were rushing to mobiles as their first taste of distant communications.

The phone companies were rolling out their networks at top speed, even though many locations needed permanent guards because otherwise the masts would be stolen and sold abroad as scrap metal. But they had built networks faster than they had in the developed world.

And then, almost surreptitiously, Michael Joseph told me about something he was about to announce in Kenya within the coming few weeks: the ability to transfer money payments round the country using a mobile phone.

For the first time, people in the cities would be able to send money home to their parents, fast, by effectively using an add-on to phone credits. Until then money had been sent up country by bus.

It meant that, for example, mothers could use their city-boy son's credit to buy chickens.

Money transfer was about to arrive in a country where the banks had not been interested in poor people, or those who lived in the country far from bank branches. A revolution was being set in place.

There are now hundreds of places offering M-Pesa in just one suburb of Nairobi

Millions of users

I could understand why Michael Joseph was so cagey about talking about it. Safaricom was in effect introducing an alternative Kenyan currency, and it was a company with a big government stakeholder.

The regulators had taken a lot of convincing about a scheme which had been dreamed up with the backing of the British government's Department for International Development.

Safaricom's mobile money scheme is called M-Pesa, M for Mobile and Pesa the Swahili for money. And it seems to have become a transformational force in Kenya and beyond, more than I grasped, and more I think than Vodafone ever expected.

The other Kenyan phone companies now offer something similar, but M-Pesa has grabbed the lion's share of the market. And how.

Six years after it launched, M-Pesa now has more than 17 million users, half the total Kenyan population. They undertake millions of transactions a month, buying credits from a dense network of 65,000 Safaricom agents who also sell the phone credits you need to use the phones (most Kenyan mobile phones are financed on pay-as-you go).

The transactions add up to one third of Kenya's total GDP. But Safaricom is not a bank, it is just a transfer agency.

The M-Pesa idea has been exported by Vodafone with varying success. In some countries such as Nigeria, the regulators are reluctant to permit money transfer like this. In other places, phones are used in different ways. South Africa is also a place where mobile money seems not to have taken off, at least at the moment.

But mobile money turns out to have been just the beginning of things, as I have been finding out on this new visit to Kenya. Technology is breaking out all over.

There are signs that the spirit I found in the informal economy may be transferring itself to a very new entrepreneurial environment, here in the heart of Africa. Certainly there are hundreds of M-Pesa shacks in the slums of Kibera.

I'll have more about Kenya's Silicon Savannah here next time.