The rise of the global middle class

- Published

- comments

The United Nations describes it as a historic shift not seen for 150 years.

The new global middle class in China, India and Brazil have propelled their economies to equal the size of the industrialised G7 countries. By 2050, they are forecast to account for nearly half of world output, far surpassing the G7.

Plus, within a decade, the middle class in Europe and North America will be less than a third of the world's total, down from more than half now.

The Brookings Institution estimates that there are 1.8 billion in the middle class, which will grow to 3.2 billion by the end of the decade.

Asia is almost entirely responsible for this growth. Its middle class is forecast to triple to 1.7 billion by 2020.

By 2030, Asia will be the home of 3 billion middle class people. It would be 10 times more than North America and five times more than Europe.

There is also substantial growth in the rest of the emerging world. The middle class in Latin America is expected to grow from 181 million to 313 million by 2030, led by Brazil. And in Africa and the Middle East, it is projected to more than double, from 137 million to 341 million.

So who counts as middle class?

According to organisations like the United Nations and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), it's someone who earns or spends $10 to $100 per day.

That's when you have disposable income and enough money to consume things like fridges, or think about buying a car.

As the UN suggests, the growth is being driven by industrialisation. The industrial revolution of the 19th Century transformed the economies of Britain, the US and Germany. The move from agrarian to industrial societies generated income rises that created the middle class.

Now it's the turn of emerging economies, particularly in Asia. In Indonesia, for instance, investment now exceeds 30% of GDP, a sign that there is more manufacturing.

The global middle class revolution

Much of the growth in the region is due to China. It is undergoing a re-industrialisation process. As the economy was industrialised in 1978 after decades of central planning, it is upgrading its industry, which has hastened the move out of agriculture.

The tough question is, why are the major changes happening now? For most of the post-war period, the surprise was why poorer countries didn't grow more quickly than rich ones.

Economic theory says that because they are further from the technology frontier, these countries can benefit from existing know-how, and thus can grow more quickly than rich ones, which grow only by innovating.

One of the reasons was hinted at by the Feldstein-Horioka paradox. The economists Martin Feldstein and Charles Horioka observed a positive correlation between national savings and national investment.

It's a paradox because, if capital truly flowed to where returns were greatest - it should go to low-stock countries because investment experiences diminishing returns. So, there shouldn't be a correlation.

It has helped to explain why investment and therefore know-how wasn't getting to developing countries - one of the reasons why they didn't "catch up".

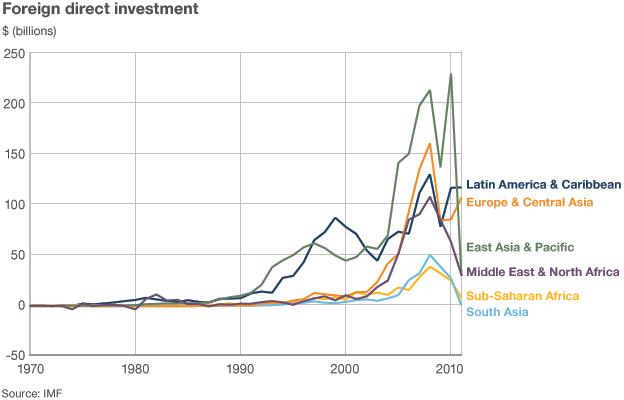

But, there was a notable change in the early 1990s.

Richard Freeman of Harvard describes it as the "great doubling." The global labour force doubled to 3 billion people when China, India and Eastern Europe re-joined the world economy.

China's "open door" policy took off in 1992, India turned outward after a 1991 balance of payments crisis and communism fell in the Soviet Union.

Those investment funds helped to generate the savings needed for emerging economies to industrialise. They also embodied the know-how that can help the catch-up process.

It is why the 2000s were the first time in which global GDP growth significantly outpaced the EU and US, and was driven increasingly by emerging economies.

Will the trend last?

One of the most remarkable feats in the world has been the lifting of about a billion people out of abject poverty in the past couple of decades.

If the industrialisation trend continues, then this century could witness some of the rapid improvements in living standards seen in the West during the 19th Century.

But, there are a number of challenges.

The UN notes that the new global middle class is likely to demand better environmental protection and more transparency in how government operates.

The importance of global integration is also why protectionism is warily watched by many.

The prize, which many will hope is in reach, is that global poverty is eliminated entirely within another couple of decades.

It is the reason why the Nobel Laureate Robert Lucas said that once you start thinking about economic growth and the improvements in standards of living, it is hard to stop.

Join me for the New Global Middle Class series on BBC World News and BBC World Service that starts today and ends on August 3rd. You can also read more online.