Too soon to call time on Abenomics

- Published

- comments

After the market euphoria which followed his election, it was inevitable that Shinzo Abe would hit a rough patch.

But today's export numbers and other encouraging signs from the real economy suggest that his radical approach is working about as well as anyone might have expected, given the enormous obstacles in its path.

Will he finally lift Japan out of its deflationary malaise? There are plenty of reasons to worry that he will not - the best being that he has not yet shown he can confront the deeper structural forces holding the economy back.

He will have an opportunity to confront the doubters in the City when Mr Abe speaks at the Guildhall in London later today. But it really is too soon to say he has failed.

Mr Abe can hardly welcome the 20% fall in the stock market in the past few weeks, and sharp jump in the value of the yen. But there's a lot of market "noise" in these movements. The global financial markets lately have not exactly been a calm and tranquil place.

The yen is still about 20% weaker, on a trade-weighted basis, than it was last year. And only part of the massive run-up in the stock market has been reversed. Even in dollar terms, the Japanese stock market is roughly 20% above its low of October 2012. In domestic currency it is 50% higher.

Higher long-term interest rates (bond yields) are not a disaster in themselves, if they reflect higher expectations for growth and future inflation. After all, Abe's plan to boost economic growth relies on persuading the Japanese people that the things they want to buy are going to get more expensive over the next few years, not fall in price, as they have so often in the past 20 years.

If that is to happen, it is crucial that the Bank of Japan remains committed to get inflation up to 2% by pumping money into the economy like there's no tomorrow.

Investors apparently now doubt that commitment, because the bank failed to loosen policy even further, in response to the market ructions. But that feels like an overreaction, on the basis of a single month's meeting.

If inflation and growth are higher, then long term interest rates (bond yields) should be higher as well. But it is important, in the short term, that yields do not rise faster than expectations of inflation. Abe needs real interest rates to be low - ideally, negative - if he is finally to encourage companies to stop saving and start investing.

Today's export numbers provide some limited evidence that one part of the strategy is working, and that Japan is starting to import some much-needed demand from the rest of the world.

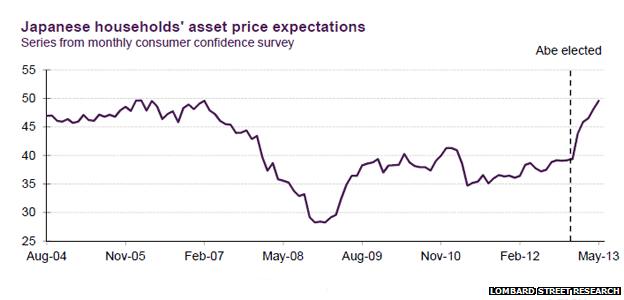

But, as Jamie Dannhauser at Lombard Street Research points out, the real test of Abe's policy will be what happens to spending Japanese households and firms.

Real private final demand grew at an annualised rate of 2.9% in the first three months of the year. That is an encouraging start. Also encouraging are reports of rising demand for household loans. That suggests people are really starting to believe that assets will be worth more in a few years' time than they are now.

The old guard at the Bank of Japan used to say that deflation would not end until Japan's political class had woken up to the need for structural change in the way the economy worked. It used to say the central bank could support this process, but it could not lead it.

Shinzo Abe has turned that logic on its head. With his new Bank of Japan governor, Haruhika Kuroda, he has made the central bank the "prime mover" in Japan, at a time when the US and Europe are also expecting the world of their central banks. That may not be all that Japan needs, but it is a start.

Back in December, I said that the world was likely to learn a lot from Shinzo Abe's efforts to revive Japan. That may be even more true today.