Spending cuts: Where are we so far?

- Published

Ben Thompson takes a look at the Spending Review figures in the BBC's virtual Treasury courtyard

Here we go again. For the second time this parliament, the chancellor will get to his feet in the House of Commons and announce a new tranche of spending cuts that have to be made by government departments.

But George Osborne didn't expect to be on this merry-go-round again. At least, the chancellor didn't when he stood up to announce his first Spending Review back in 2010.

At that time it was his intention that the structural deficit (the gap between tax receipts and government spending when the economy is operating at full capacity) would be eliminated by 2015. This would mean he would have to make no more cuts before the general election, which is due to be held in that year.

Unfortunately, it didn't quite work out that way. A poorly performing economy meant the amount of money the chancellor took into the coffers wasn't as large as he thought it would be.

As a result, the chancellor plans to close the deficit by the 2017-18 financial year, some three years behind schedule.

As a consequence, he is having to make more cuts worth an extra 2.8% of departmental spending. It's also likely we'll have another set of cuts after the next election, whichever party is in power.

So, the rather unsettling thing for politicians and public alike is, we are not out of the woods yet. Indeed we're only just over half way through and this week's Spending Review represents a relatively small proportion of the cuts the chancellor says are still to come in the next few years.

But what of the cuts announced so far? Most have already been made.

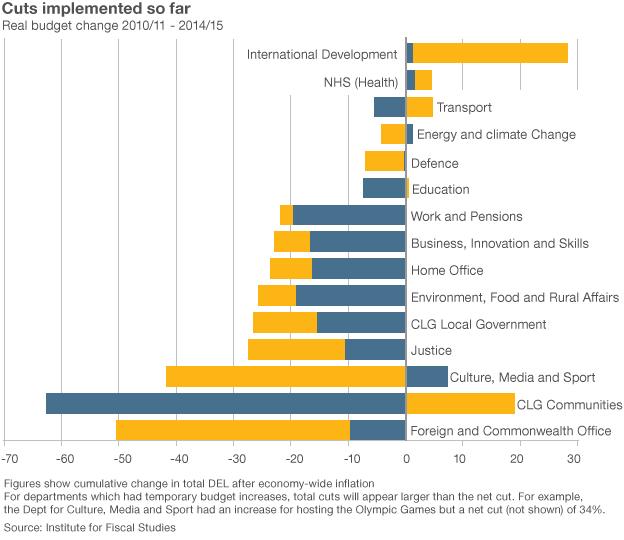

The spending cuts the chancellor announced in 2010 will be largely completed by 2014-15.

But some departments have not completed their cuts as quickly as others. Some departments, notably the foreign office, culture and defence still have a long way to go (notably, international development's increase - the bugbear of the prime minister's backbenchers - is still largely to come).

Moreover, as a result of the ring-fencing of certain departments (health, international development and the schools budget in England), the cuts other departments have experienced have had to be far deeper. The foreign office, for example, will have lost over half its budget in a period of just four years.

That process seems likely to be repeated this time round, with the government pledging to continue to ring-fence certain areas. Even within the non-protected departments, some are likely to receive preferential treatment.

Home Secretary Theresa May and Defence Secretary Philip Hammond in particular are said to have lobbied hard to protect their departments at the expense of others.

If, as expected, the Home Office and the Ministry of Defence are spared the axe more than the others, some departments could be reduced to half the size they were only five years ago.

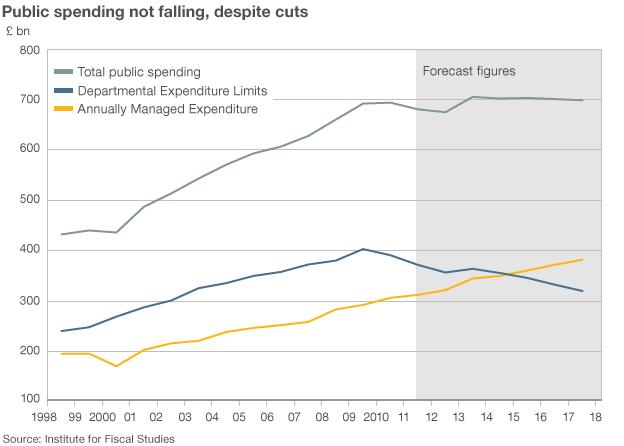

And yet, despite all these changes, government spending overall is broadly similar to the level it was before the start of the present government.

That's right. Despite all the pain, all the cuts, all the ministerial nail-biting, the government has not succeeded in bringing down overall spending by very much at all. This leads to the oft-repeated claim that the government is not really engaging in austerity at all.

How is this circle squared?

Well, the government has been much more successful than many had predicted in cutting spending by departments. This is expected to be 9% lower by the end of the 2014-15 financial year than it was at the start of 2010.

However, it has not managed to cut the parts of its budget that don't fit into neat departmental categories: things like debt interest payments, pensions and benefits. In the jargon this is known as Annually Managed Expenditure (AME). This is distinct from the budgets set for individual departments, which are known as Departmental Expenditure Limits, or DEL.

Since the government started its austerity drive, AME has been rising just about as fast as DEL has been falling.

For the government then it has been something of a case of one step forward, two steps back. This is part of the reason Labour has floated the idea of a cap on the AME section of the government's budget.

Save for a return to steady growth, until those issues are addressed, no government of any colour is likely to get off the spending cuts merry-go-round any time soon.