Cash crunch? China's true crunch time is yet to come

- Published

- comments

China's 'shadow banking' sector could pose serious problems for the country in future

How can a largely state-owned banking system experience a credit crunch? When the central bank decides to rein back credit.

The Chinese central bank has been reining back credit for some time now as it has sought to control housing prices. But, when the cheap money from the rest of the world began reversing (see my post on Great Reversal part II) due to the Fed signalling an end date for the era of cheap money, funds leaving emerging economies like China have made the situation more apparent.

Last week, the overnight lending rate between banks jumped to exceed 25% as banks became reluctant to lend to each other. But the lending rates fell again when the state-owned banks fell into line and resumed lending to each other.

Now, the Chinese central bank says that liquidity is "ample" and essentially indicated that it will not inject more cash, holding firm on the line of controlling credit growth in the economy.

As a result, the Chinese stock market fell into bear market territory led by the decline of banks. In other words, banks can't count on the central bank for cheap cash. In fact, the central bank wants to root out the poorly performing banks - especially those in the so-called shadow banking system.

Unintended consequence

Shadow banks in China, as I have said before, are not like Western shadow banks. They share the similarity of being worryingly outside the formal regulatory framework, but they aren't complex entities trading complicated financial instruments like derivatives. They carry out normal banking activities, namely lending, but without a banking license.

The growth of this sector was almost an unintended consequence of the partial liberalisation of interest rates in 2004. In other words, China doesn't have one market-clearing interest rate, but controlled benchmark rates that set the cost for lending and deposits.

They have been aiming to reform capital markets to better price for risk. And like many Chinese reforms, they did it gradually and partially. Unfortunately, in financial markets, they ended up bolstering informal lending that is the new frontier in concerns over the Chinese banking sector.

China lifted the "ceiling" on the lending rate and the "floor" of the deposit rate in 2004. At present, there is still a "floor" on the lending rate of 6% and a "ceiling" on the deposit rate of 3%, although banks can now exceed the limits of both these benchmark rates by some 10%-30%.

With the ability to earn higher returns through lending, unlicensed banks started doing so at reportedly double-digit rates. Funds even came from savers seeking better returns for their money. This is because, after inflation, the interest earned on deposits was sometimes negative in the post-global crisis period.

Off balance sheet

When coupled with few other avenues to put their money, there was unsurprisingly rapid growth in the informal lending sector.

That isn't the only reason for the growth of the shadow banking system.

Local governments have used off balance sheet vehicles to borrow from state-owned banks, especially since they were at the forefront of the government's large-scale stimulus measures to cope with the 2008 global financial crisis. Part of the problem is that China's municipal bond market is under-developed, so local governments can't simply borrow from debt markets and end up relying somewhat covertly on banks.

The Chinese government is trying to curb this behaviour and have also started to allow local governments to issue bonds more independently to reduce the incentives to rely on banks.

The result is that debt has grown quickly in China since the global financial crisis when they unleashed a large amount of credit to help stimulate their economy.

How national debt levels have changed

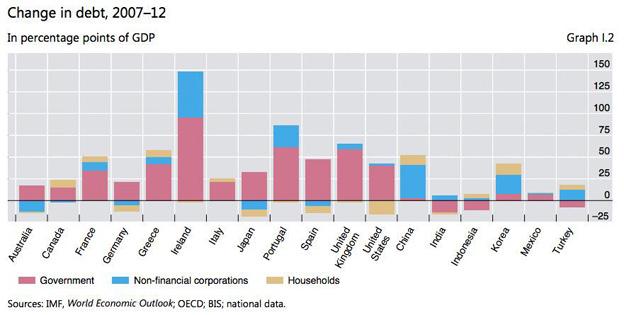

The central banks' central bank, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), in its latest annual report, reveals that the growth of debt in China since 2007 is an astounding 50 percentage points of GDP.

Comparatively, it is the fifth largest increase in debt among major economies, after only the rescued countries of Ireland, Portugal, and Greece, as well as Britain (that had a banking crisis and rescued its banks).

Also, unlike those countries where the growth in debt is from government borrowing, most of China's increase in debt is due to companies borrowing. And thus China's concerns over too much lending, including from the shadow banking system. Local government borrowing is largely off balance sheet, so it doesn't show up necessarily in government debt levels.

This growth in debt in a shaky banking system is why China's central bank is holding a firm line on injecting more cash into the system. The real crunch time is likely to come if the Chinese economy slows below the government's 7.5% target, and there is pressure to raise growth through easing the terms for lending. That is when the resolve of the central bank will truly be tested.

Cash crunch? China's true crunch time is yet to come