Nelson Mandela: His economic legacy

- Published

While South Africa's economy has grown since 1994, more employment opportunities need to be created to reduce high unemployment

When Nelson Mandela stood in front of the Union Buildings in Pretoria 19 years ago to be sworn in as South Africa's first democratically elected president, he embodied the hopes of a nation.

Apartheid was vanquished, and in its place the rainbow nation was born. It was a time of great optimism.

There was much work to do, but there was a feeling that if everyone pulled together, a post-apartheid dream could be realised.

Much of that dream in economic terms was based on the Freedom Charter - the document signed in 1955 by Mr Mandela and others opposed to apartheid. It promised work and education for all, and a sharing of the country's vast natural resources.

By the time apartheid came to an end, the South African economy had spent years being battered by sanctions. The infrastructure was, and remains, the most highly-developed in Africa, but the years of economic isolation were taking their toll.

In some senses, Mr Mandela and the African National Congress (ANC) inherited an economy that was heading for bankruptcy.

So, it was to prove a difficult task to create a silk purse of an economy from the pig's ear that Apartheid had left behind. However, many analysts point out that great strides were made in delivering some of the Freedom Charter aspirations in the early years of the new South Africa.

Dawie Roodt, chief economist at the Efficient Group, says: "Many millions of people got running water, electricity, etc.

"But the infrastructure was neglected, and slowly state inefficiency and corruption became serious problems."

A good start

On the surface, at least, things looked good at the start. Inflation, which was running at 14% before 1994, fell to 5% within 10 years.

South Africa's budget deficit, which was 8% in 1997, fell to 1.5% in 2004. Interest rates dropped from 16% to under 9% in the first decade of the ANC government.

Once sanctions were dropped, South African exports blossomed. Before Mr Mandela took the oath of office, just 10% of the country's goods were earmarked for export. By the turn of the century nearly a quarter of them were.

It wasn't just economic numbers on sheets of paper. In the 14 years after 1996, the proportion of South Africans living on $2 (£1.22) a day fell from 12% to 5%.

Annabel Bishop, group economist at Investec, says South Africa's economy has "essentially doubled in real terms" since the fall of apartheid, growing at an average of 3.2% a year since 1994, as opposed to only 1.6% per annum for the 18 years prior to the end of white minority rule.

She also points out that the real tax revenues have effectively doubled since 1994, which has enabled the government to expand social welfare.

"The state provision of basic services has been extensive," she says.

But the early years still had to contend with huge problems. Apartheid had created rampant unemployment among the black population, an albatross that continues to hang around the economy's neck almost two decades later.

South Africa's official unemployment rate has hovered around 25% for years, and youth unemployment is much higher. By some measures half of those under 25 are out of work.

President Jacob Zuma is acutely aware of this. It's a situation that, combined with falling education standards and a skills shortage, is storing up problems for the future.

"We have developed a number of sectoral strategies especially focusing on skills development to meet these challenges," Mr Zuma has said.

While overseas companies scrambled to get into the newly open economy after 1994, the foreign direct investment (FDI) didn't transform into the millions of jobs that were needed.

The general secretary of the trade union organisation, Cosatu, Zwelinzima Vavi, recently said: "While we have made huge gains since 1994... on the economic front workers' lives have not been fundamentally transformed. We still face massive problems in our economy."

Wide inequality

One of the massive problems is the gap between the rich and the poor, which in South Africa is one of the highest in the world. In fact, by some measures it's actually greater than it was under apartheid.

Under the commonly-used Gini coefficient for measuring inequality, South Africa scored 0.63 in 2009. Under the coefficient, 0 is the most equal and 1 is the the least equal.

Back in 1993, the country's rating was 0.59, which has led many to the conclusion that the gap between the rich and poor is actually getting bigger.

Meanwhile, the United Nations regularly ranks South Africa's cities as some of the most unequal in the world.

Poverty still remains a problem in South African's townships

But coefficients and reports aside, the most casual of observers only has to drive the few miles across Johannesburg or Cape Town to go from views of stunning mansions with German cars, to shacks and open sewers.

Lerato Kabwe, a business woman in Johannesburg, says she felt more economically confident during Mr Mandela's presidency than she does today.

"We basically don't know where we're heading," she adds.

"Everything is expensive. How do we survive? The opportunities are very limited.

"We're far from economic freedom because the minority that was previously empowered - they still have economic power. When will the equality happen?"

Bank employee Peter says he's "hopeful, but at the same time, negative towards the economic outlook".

"Nevertheless I think, right now, we are getting more opportunities, as opposed to prior to Mandela being elected as our president," he adds.

While much was done and planned in the early post-apartheid years to right the wrongs of the previous era, analysts say that many policies faced insurmountable problems.

Initially, Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) was a "quick fix" - giving black South Africans a stake in the nation's industries from which they had so long been excluded.

However, in the first 10 years of the new ANC administration, the fruits of the BEE policies tended to end up in the pockets of a politically well-connected elite.

Even though the BEE policies expanded over the years and helped create a rapidly expanding black middle class, they still largely failed to improve the lot of the majority.

Marikana mine shootings

A case in point in the inequality picture is South Africa's mining sector. 2012 was the most turbulent year for the country since the end of the apartheid, with violent wildcat strikes across the sector, and 34 miners shot dead at Lonmin's Marikana platinum mine in Rustenburg.

The problems at the Marikana mine could be seen as a microcosm for the country

In a way the Marikana mine is a microcosm for the country. The workforce is split, largely between the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) and the Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (AMCU).

The board of Lonmin is mostly white, although until recently the ANC's new deputy president Cyril Ramaphosa had a seat. Mr Ramaphosa is often tipped as a successor to President Jacob Zuma. He's also a former head of the NUM.

A combination of factors meant the lowest-paid and least-skilled workers at Marikana began to slip behind. In an industry where the average wage supports 10 people, these men were on the wrong side of the wealth gap. They also began to view the NUM as being too close to Lonmin to efficiently look after their interests.

So, they downed tools in an unofficial, wildcat strike to increase their wages. That culminated in the dreadful events at the Marikana mine on 16 August of last year.

So, Marikana has a militant, disaffected and divided workforce. It has one union that is seen as being too close to the management. It has another that has severed ties, and is hostile to both the white owners and the long-established union. It may be a case of "so goes Marikana, so goes the nation".

'Self-enrichment'

Forward Mutendi, a consultant in Johannesburg certainly doesn't want Marikana to become a mirror for his country's economy.

"I've never seen a country, I've never seen a situation, where unions are fighting against each other," he says. "This is really showing that there's no longer discipline and now everybody's individualistic.

South Africa's economy continues to grow

"Right now, this is deterring investors from coming back to invest in the country and a lot of people are losing jobs."

Corruption is often put forward as a serious hinderer of economic growth in South Africa, not just from the corporate sphere, but from organised labour as well.

Cosatu's Zwelinzima Vavi says it's a scourge that's doing "untold damage on the moral fibre" of South Africa.

"We are moving towards a society in which the morality of our revolutionary movement... is being swept away [by] a culture of individual self-enrichment and 'me-first'," he recently told a gathering at the University of Cape Town.

Brics membership

Yet other analysts think the current pictures being painted of South Africa's economy are far too bleak. Yes, there are big problems they say, but that doesn't mean that South Africans are incapable of finding big answers.

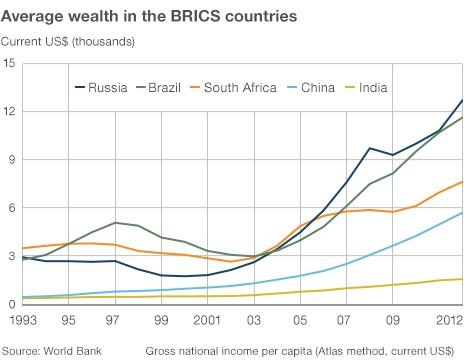

South Africa's economy remains the largest on the continent, even though there's evidence that Nigeria is catching up fast. Together with Brazil, Russia, India and China, South African is a member of the Brics grouping of emerging market nations, with all the potential that brings.

South Africa is the 's' in the Brics group of leading emerging nations

While its mining sector may be going through turbulent times, its financial services sector is highly developed and thriving.

Economist Dawie Roodt says: "We still have time to fix certain negative trends, with strong political leadership we can turn the ship around, but strong leadership often lacks.

"We also have significant policy uncertainty because of weak leadership."

Mr Mandela's economic legacy stems from the political freedoms for which he fought and won. It's a framework where, in theory at least, all South Africans have the right to pursue their economic dreams.

As the busy lunchtime pedestrian traffic bustles around him in downtown Johannesburg, Chris Nkasa, who works at a computing firm, ponders the question of Mandela and his economic legacy.

"He has done a lot [on economic freedom]," he says. "It's up to us to take it forward. It's up to us now."