The luck of the Canadians (and Mark Carney)

- Published

- comments

Stephanie Flanders reports from Toronto on a "financial rock star"

Before Mark Carney comes here as the next governor of the Bank of England, I thought I should go there, to get a closer look at his record in Canada, and decide for myself whether he's anything like as good as he's cracked up to be.

My conclusions? He didn't singlehandedly rescue the Canadians from the worst of the global financial crisis - he didn't really need to. But boy, did he win over the press.

Britain's press corps like to think they're more hard-nosed than their Canadian counterparts. Meaner. Less easily impressed.

Perhaps. But I've read what the Canadian press say about other Canadian policy makers, and I've read what they said about Mark Carney after five years in the hot seat at the Bank of Canada. It's like night and day. One paper put Carney at the top of its list of "Canadians abroad that we want back". Before he had even left.

I can't help thinking the hard men and women of Fleet Street might find themselves charmed as well. This is a man who established a reputation as a "working-class hero" to many Canadians, despite having spent 13 years at Goldman Sachs.

Then again, Canadians don't have nearly as much reason to dislike bankers. Canada is the only G7 country that has not had to spend any taxpayer money bailing banks out.

'Timely stimulus'

That is not strictly down to Mark Carney, though he had a role in improving bank regulation at the Bank of Canada and also during his time at the Department of Finance.

But it is one of the things that made his job quite a lot easier, since the start of the financial crisis, than Ben Bernanke's or Sir Mervyn King's.

Canada's economy is nearly 5% larger now than it was five years ago. Britain's is more than 2% smaller. Inflation has also been a lot lower under Mark Carney: 1.7%, on average, versus 3.2% in the UK.

The OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) says the Canadian economy bounced back so quickly from the 2008-09 crisis "thanks to timely monetary and fiscal stimulus, a sound financial system and high commodity prices."

You can't help noticing that only one of those four advantages is directly attributable to Mr Carney.

As I've discussed before, Canada's banks were conservative, going into the crisis. So were its financial regulators. Compared to their friends across the border, the big Canadian banks did not end up with a lot of bad debt - and the bad debts they did acquire, they had made much better provision for.

Mark Carney's Bank of Canada appointment surprised many

The fact that Canada is a big commodity producer and exporter also made a key difference: those big commodity price rises that have made us so much poorer in the past few years, by pushing up inflation, have largely been making Canada richer.

As we know, Canada was also helped by having got its fiscal crisis in early. The government spent most of the 1990s doing, in effect, what George Osborne is doing now. (Though the Canadians had the good luck to be doing it when everyone else was doing well. I'll return to Canada's good timing in a minute.)

All that past austerity meant that Canada had a lot more room to turn on the taps, with a big increase in public investment and other stimulus policies which increased borrowing by more than 4% of GDP between 2008 and 2010.

That's twice the OECD average and much larger than Gordon Brown's rather feeble stimulus programme.

So - Mark Carney was dealt a strong hand. But nearly everyone I spoke to in Canada still gave him credit for playing it well.

I didn't know, before my trip, that he was a surprise pick for his last job as well. A few weeks before, 36 economists were asked who would get the job as governor of the Canadian central bank.

Nearly all thought it would be Paul Jenkins, the senior deputy governor and long-time insider (sound familiar?) Only three thought Mark Carney was in with a chance.

When he came in, he quickly made his mark by cutting interest rates by half a percentage point in his first month. That was in March 2008, remember, when other central banks still thought the financial crisis would blow over. The ECB was actually raising rates.

'Moment of truth'

That early rate cut helped make Mark Carney's reputation. He also gets credit for using "forward guidance" to convince people the central bank was serious about keeping policy very loose. There'll be plenty more to say on that subject, in the next few weeks.

But most other central banks did slash interest rates a few months later, also to record lows. The difference was that it worked in Canada - because the banks were willing and able to lend.

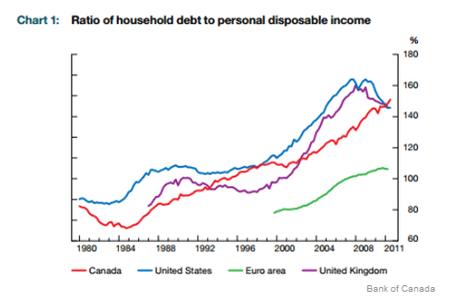

That produced a feel-good factor and a pretty reasonable economic recovery. It also produced a rocketing housing market, a big current account deficit, and rising household debt. So yes, he does have some experience relevant to the UK.

Paul Krugman says this all makes Canada a test case, external for two somewhat different views of the financial crisis and its aftermath.

One view says that it was primarily down to the banks and their problems. If that's true, you'd expect Canada to stay out of trouble, for all the reasons I've already discussed.

The other view is that the banking crisis was just a sideshow for the main event which was the housing boom and bust and the long-term implications for the economy of households being stuck with so much debt.

I'm not sure anyone thinks any more that 2008-9 was "just" a banking crisis. For a Nobel prize winning economist, Paul Krugman has quite a weakness for straw men.

How does Mark Carney's reputation as a central banker stand up?

But when you look at what's happened to Canadian house prices and personal debt ratios, you do have to wonder whether Canada has simply postponed its moment of truth.

At this point, it's traditional for us "hard-nosed" UK economics journalists to joke that Mark Carney is "getting out of Canada in the nick of time". We'll see.

Maybe our new central bank governor is lucky as well as charming. But you'd have to say, it's lucky for Canada, too, if it has once again been able to postpone its day of reckoning, to a time when its neighbour and main trading partner is on the mend.

George Osborne isn't the only one wishing we could have been so lucky in the UK.