Egypt's upheaval raises middle-class brain drain fears

- Published

Nabila Hamdy and her children are among many middle class families leaving Egypt

Since the toppling of Hosni Mubarak in 2011, many of Egypt's middle class have felt let down with basic state services such as education and security - some have even decided to leave. It's a group whose talents are vital to the country's economic future.

Pushing her twin daughters back and forwards on swings in the garden, Nabila Hamdy is all smiles.

With a spacious home, four healthy children and a nanny to help look after them, she knows she has plenty of reasons to be contented.

But part of the reason for her happiness is that she is leaving behind the house, the garden and the nanny (not to mention her driver) to start a new life in the UK with her husband, airline pilot Mohamed, and youngsters Zeina, Zein, Aisha and Fatma

"My husband has been wanting to leave for the past 10 years, but I've been saying, 'No, no, it's Egypt, it's home,'" 36-year-old Nabila says.

"I'm very proud of Egypt, but since the 2011 revolution things have been bad here, really bad. There's no police, no sense of security, no sense of safety. You're afraid and it's scary."

Lifestyle change

The move to the UK, where the couple have a house, was pretty much complete by the time Egypt's latest power struggle saw Mohammed Morsi forced from office.

And while Nabila deplored what she argues were changes in society under a Muslim Brotherhood-led government, especially a sense that women were being treated as second-class citizens, the family's minds were made up despite the power shift.

"I won't have the same lifestyle, I won't have the help I am used to," Nabila says.

The global middle class revolution

"But I will be able to guarantee that my kids will be able to walk the streets safely, that my girls will grow up being treated with respect. I am blessed to have this opportunity and though I love my country, I love my kids more."

Societal changes

Her family are at the top end of a very broad group in Egypt that defines itself as middle class.

And while numbers are hard to pin down - and though there are some exiled Egyptians returning to their homeland - Nabila is not alone in choosing to leave,

"We're hearing there's quite a trend of a brain drain this summer," says economist Angus Blair, president of the Cairo-based Signet Institute.

"These are people in the middle class who don't like some societal changes that are happening - increased intolerance, perhaps interference in the way that they live."

He cites reports from one private school that 200 of the 1,500 Egyptian pupils have not been enrolled for the autumn term.

And while this might be partly down to parents rethinking school fees during a time of double-digit inflation, Mr Blair believes it is also the result of middle-class families leaving the country.

"I think that's a shame because Egypt could do with this class of entrepreneurs and others who also take some form of decision in society," he adds.

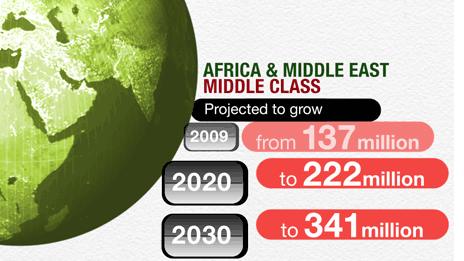

Source: UN/Brookings Institution

Price pressures

Middle-class Egyptians played a big part in the overthrow of Hosni Mubarak early in 2011.

And it was a disillusioned middle class who were among the hundreds of thousands on the streets across Egypt last week, pressure that led to Mohammed Morsi being pushed out as president.

It was news greeted optimistically by Samir Abdel Aziz Saber, who lives with his wife and three children in an apartment in a dusty Cairo suburb where donkeys still compete for space with cars on the road.

Samir Saber is still paying for private schooling even though the family's cost of living has gone up by 30%

Though his living conditions and income from work in a firm of architects are far below those of Nabila's family, the 40-year-old also considers himself middle class.

He has no plans yet to pull his eldest boys Hassan and Said out of private school even though he is struggling to pay the fees, with his salary largely unchanged but the price of food up by as much as 30%.

Sitting on the sofa helping the boys with homework, he admits one way to make money would be to find work abroad.

But as he could not afford to take his family, he will not be joining the movement of middle-class Egyptians seeking a better life overseas.

"I prefer to stay with my kids and be next to them when they are growing up," Samir says.

"I have to be with them whether the country is OK or not - I have to be with my kids. If I think of going somewhere else, to me this is like running away."