Indian rose growers raise scent of division in Ethiopia

- Published

A two-hour drive from the Ethiopian capital Addis Ababa takes you to the Wolisso region where Indian multinational Karuturi has a farm spread over 156 hectares (385 acres). Only a fifth of the farm is under cultivation, growing several varieties of rose. This is one of the four farms run by Karuturi.

Activists accuse the Indian company, and several foreign enterprises, of grabbing land in Africa at dirt-cheap rates. They say it is hurting local communities, their displacement is not being adequately addressed, and Africa is losing precious resources. But the Ethiopian government and the companies reject the allegations.

The Ethiopian government says it still has plenty of land to be developed and that it is using land as an “instrument to promote investment” but adds that Karuturi is “lagging behind the target of developing the land”.

Mekedes Demena makes flower bunches and has been working for more than a year on the farm. She says she makes a good living. “From what I earn here, I can save some for myself,” she says. Many local workers depend on this farm for their livelihoods.

Fantu is in the quality-control section and has been working for two years. “If I was not working here, I would not have been doing anything. I would have been wasting my time in the village,” she says.

Issues such as food security, rising land prices, lack of irrigation facilities, increasing numbers of land disputes and farmer protests have forced companies in India to look abroad to acquire land. Agriculture is the mainstay of the economy in Ethiopia and it needs investment to modernise its farms.

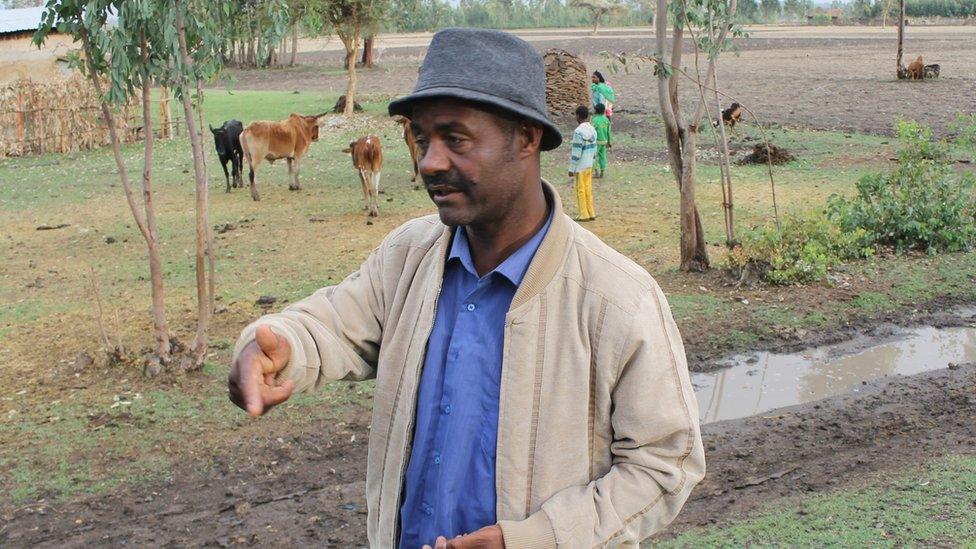

Some Ethiopians resist the presence of foreign companies. Ayansa Waktola, who lives near the farm, says: “The farm is not benefiting us. Employees receive low incomes, which do not cover their personal expenses. This kind of employment may be OK for a short period, but not in the long run.”

The Oakland Institute, a US think tank, says Indian companies are the biggest investors in the Ethiopian agro-sector. They put $4bn into Ethiopian farmland between 2006 and 2009, it says. Pictures and text by Vineet Khare.