End of the road for Jeepneys in the Philippines?

- Published

The Jeepney, ubiquitous in the Philippines, is the cheapest mode of mass transport there

It is a form of self-expression - no two Jeepneys are decorated in the same way

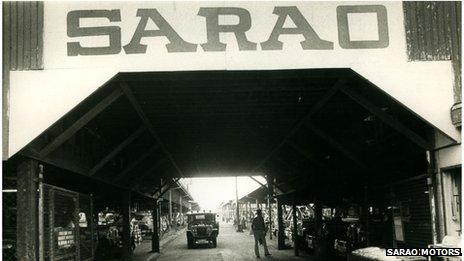

Sarao Motors was one of the first companies to take old US army vehicles left behind after World War II and customise them for mass transport

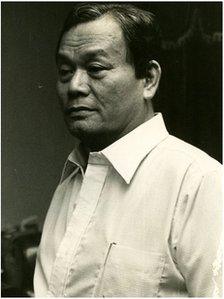

Leonardo Sarao founded the company, helped by his brothers

Mr Sarao use to drive a kalesa - or horse-drawn cart - but saw the opportunity in mass transport. His old kalesa is still kept in the workshop today

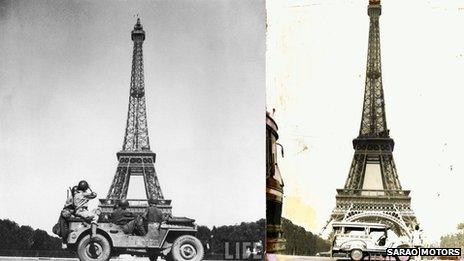

In the 1970s Sarao Motors promoted the Jeepney all over Europe as part of a campaign by the Philippines' tourism department

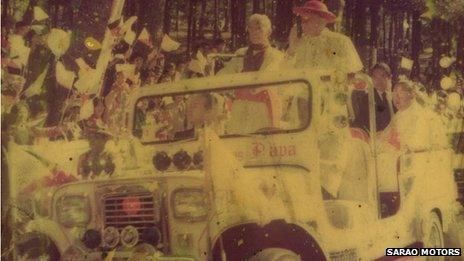

During a visit in 1981 by Pope John Paul II, he waved to the crowds gathered along the route from a specially-made Sarao Jeepney

The original Jeepneys were fitted with diesel engines, but the newest incarnation of the vehicle runs on electricity

London has the red double-decker bus, New York the yellow taxi, and the Philippines has the Jeepney.

The country's most popular means of public transport zipping by adds a flash of vibrancy in the often frustrating, gridlocked streets of metropolitan Manila.

With names like Delilah and Rosa emblazoned across the front, each one is individually adorned with religious and nationalistic artwork - no two are identical.

For Ed Sarao, head of Sarao Motors - one of the first makers of Jeepneys - the vehicle represents the multi-cultural history of the Philippines.

"There is bit of Spanish, Mexican traits there; how they incorporate vivid colours, fiesta-like feelings. There is a little of the Americans because it evolved from the Jeep. There is a little Japan because of the Japanese engine. But it was built by Filipino hands," he says.

But while it was once part of the Philippines' image and identity, the Jeepney has now become something of a dinosaur - and newer, more economical vehicles are starting to take its place.

King of the road

Leonardo Sarao started Sarao Motors in 1953

Jeepneys first hit the roads in the 1950s, refashioned from military vehicles left behind by US soldiers after World War II.

Some entrepreneurial Filipinos took those US Jeeps and modified them, adding features to make them roadworthy, and creating a new form of mass transit.

One of those entrepreneurs was Leonardo Sarao, who at the time drove a kalesa, or horse-drawn cart.

"He saw the opportunity in having public transportation around Manila," says Ed, who still keeps his father's old kalesa in the workshop.

Jeepneys can carry about 18 people - packed in shoulder-to-shoulder, with glassless windows for ventilation in the hot climate.

Operated by owners who run franchises, for average Filipinos they are still the cheapest way to get around, costing about eight pesos (20 US cents; 12 pence) for a ride.

Financial reality

At the height of their popularity, when Ed describes the factory floor as a bee hive buzzing with activity, Sarao Motors was asked by the tourism ministry to showcase its vehicles around the world.

But the heyday came to an end shortly after the Asian financial crisis in 1997-98.

Ed says Sarao Motors has never really recovered. It has gone from churning out 12-18 units a day to producing just 40 a year.

Ed Sarao from Sarao Motors describes the ups and downs the company has faced

The reason for the decline in the company's fortunes, and the fall of the Jeepney in general, is purely financial, says Jamie Leather, principal transport specialist at the Asian Development Bank (ADB), which is headquartered in Manila.

He explains that Jeepneys are more expensive to operate and repair than other vehicles on the market because they don't have standardised parts that are readily available.

Other vehicles may take fewer passengers, but are more profitable for operators and so some of them are opting to replace their Jeepneys, Mr Leather says.

"Passengers also prefer air-conditioning that other vehicles provide - they see it as more comfortable," he adds.

Modernise transport

The other reason Jeepneys are now at odds with the future of transportation in the Philippines is the amount of carbon dioxide they emit from their diesel engines.

The Philippines is struggling to combat air pollution - the ADB estimates that 5,000 people die from air pollution-related illnesses every year.

So, in an effort to keep the nostalgia but not the fumes, one organisation is testing electric Jeepneys in the central business district of Makati, one of the cities that makes up metropolitan Manila.

In an effort to fight air pollution, 10 electric Jeepneys are being operated in Makati City

The Institute of Sustainable Cities has awarded a franchise to the E-Jeepney Company to operate 10 electric Jeepneys.

"We are trying to modernise the transport system in the Philippines," says Yuri Sarmiento, the head of E-Jeepney.

Their vehicles charge overnight at a makeshift hub inside the Makati Fire Station. During the day they go on fixed routes, picking up passengers from designated stops.

Of the roughly 50,000 Jeepneys roaring around Manila on any given day, they are hoping to replace about 2,000 of them with e-Jeepneys by 2015, and eventually to have 10,000.

"We use it as a vehicle for change to grow awareness among Filipinos to use alternative fuel," says Mr Sarmiento.

"The Jeepney fits that role perfectly."

Back at his workshop, Ed Sarao says he is also considering what the next phase of the Sarao Jeepney will be, whether it is electric or perhaps air-conditioned models.

Despite the tough times his company is going through, he's not giving up yet.

"Filipinos are very resilient," he says, and he hopes that the vehicle his father pioneered will prove to be resilient too.

- Published30 July 2013

- Published15 May 2013

- Published21 June 2013