Syria crisis: Economy of Jordan's Zaatari refugee camp

- Published

Businesses operate out of Zaatari refugee camp. Howard Johnson reports.

The door of a metal cargo container creaks open to reveal a row of embroidered and bejewelled dresses in red, pink and white.

I had stepped into Atef's wedding dress hire shop, a business that serves as a reminder that romance blossoms in the bleakest of environments.

Atef's business in is the Zaatari refugee camp in Jordan, home to about 120,000 people who have fled the conflict in Syria.

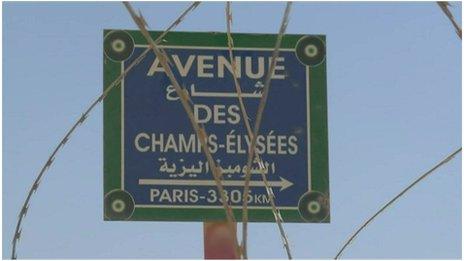

His container is located on a street that aid workers have nicknamed the Champs Elysees, due to the hundreds of shops and businesses.

Atef has been in the camp for over a year now. He fled the fighting in Daraa, about 30km (20 miles) away in Syria. It is a city rich with businessmen thanks to a long history of cross-border trade with Jordan.

"We started this as an abaya (robe for women) shop," says Atef.

"Women used to come here and say they had weddings but they couldn't find dresses. So we bought two dresses for rent and it worked out well.

"We have two weddings a day and there are people who come from outside the camp to rent dresses because it is cheaper here.

"The profit is not that much but we are doing ok. We rent the dress for 10 dinars (around $14) whether it's people inside or outside the camp.

"Sometimes we even take 5 dinars from people who can't afford to pay much."

Atef runs a wedding dress hire shop in the refugee camp

Atef's wedding shop is an example of how the UNHCR, the UN's refugee agency, is trying to create a sense of normality in the camp by encouraging trade and services.

If people can look after a shop and turn a profit, then peace and stability in the camp improve. At least that's the theory.

Since the camp opened last year, there has been black market activity, with rival gangs attempting to control the illicit sale of aid goods and the siphoning off of camp electricity supplies.

Smugglers wait at night on the outskirts of the camp ready to take away UNHCR tents and food supplies.

The man tasked with tackling the camp's black economy is Kilian Kleinschmidt, the UNHCR-appointed "mayor" of the camp.

Blocking smugglers

A veteran of humanitarian work, he has managed refugee camps in South Sudan, Somalia and Kosovo.

To give me a sense of the scale of the camp, Mr Kleinschmidt showed me around the camp's 8km (five-mile) perimeter road.

It is the front line in the battle against illegal trade.

He points out of the window. Plumes of black smoke rise from bulldozers as they plough up mounds of soil. "We're blocking the supply routes to the smugglers," he says.

Next, he draws my attention to large rectangular scratch marks in the earth: plots of land, marked out by rival gangs laying claim to the territory. An informal property market is also blossoming in the camp.

Halfway around the loop, what looks like a caravan is being pushed by a group of men. As we get closer, it becomes clear that it is a residential container, towed on a makeshift rig on wheels.

The containers, mostly donated by Gulf nations, are being sold to, or acquired by, gangs who either trade them in the camp, or cut them up and sell them outside.

Back in Mr Kleinschmidt's meeting room, my eyes are instantly drawn to an interactive map complete with Lego bandits and sage-looking Smurfs.

Kilian Kleinschmidt, the UNHCR-appointed mayor of the camp, has a plan for the camp

The map shows his plan to create district councils to help bring calm and stability to the camp.

"Is it ok to take a photo of this map?" I ask, not sure if it is for UNHCR eyes only.

"Sure," he says, "John Kerry [US Secretary of State] played with it when he came to visit."

After moving cake to where food is distributed, Mr Kleinschmidt explains that as the war drags on in Syria, a sense of permanence is taking hold in the camp.

"The sad sense of reality has come in, that residents are here to stay," said Mr Kleinschmidt.

"Homes are being built with cement floors and water; toilets, showers and kitchens are being added.

"Some even have a fountain to show that it is just like home,"

So how does he intend to tackle the camp's burgeoning black market?

"We are saying, brothers, maybe now is the time you pay for electricity because I checked with a few of my friends who are grilling and roasting chickens.

"One of them told me he's selling a hundred chickens a day.

"So roughly he makes a $2 profit on one chicken. So easily he makes $200 profit a day.

"So am I going to cut him off? No. But I'm going to tell him I will supply him with the electricity but he will pay.

"And you know what, they are smiling and saying yes," said Mr Kleinschmidt.

The main street of the Zaatari refugee camp has been dubbed the Champs Elysees

Before my day's visit to Zaatari is up, I take one last stroll along the Champs Elysees. A father and his child are spinning candy floss, ready for an evening of brisk trade.

Suddenly a group of youths begin running. After a long hot day, a scuffle has broken out with the Jordanian security who police the camp.

Tear gas canisters clatter over the camp's corrugated metal roofs.

No one was seriously injured, but the incident serves as a reminder.

Despite the best efforts of the UNHCR to normalise the camp, for now, Zaatari's Champs Elysees remains far from its French namesake as a place for doing business.

- Published9 August 2013

- Published9 August 2013

- Published10 August 2013